This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The biblical narrative of Sodom and Gomorrah has served as an archetypal story of divine antipathy towards same sex love and desire. 'Sodomy' offers a study of the reception of this story in Christian and Jewish traditions from antiquity to the Reformation. The book argues that the homophobic interpretation of Sodom and Gomorrah is a Christian invention which emerged in the first few centuries of the Christian era. The Jewish tradition - in which Sodom and Gomorrah are associated primarily with inhospitality, xenophobia and abuse of the poor - presents a very different picture. The book will be of interest to students and scholars seeking a fresh perspective on biblical approaches to sexuality.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

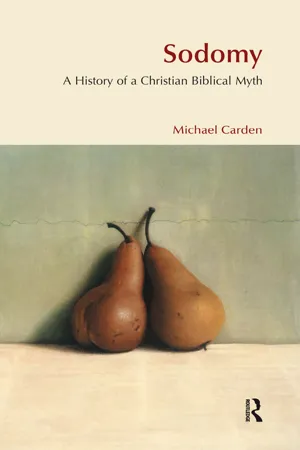

Yes, you can access Sodomy by Michael Carden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

INTRODUCING SODOM/OLOG/Y:

A HOMOSEXUAL READING HETERO-TEXTUALITY

A HOMOSEXUAL READING HETERO-TEXTUALITY

1. Motivation: Suicide, Biblical Studies and Social Control

Throughout 2001 I was a member of a Queer Men’s Discussion Group that met regularly at Queensland University. At one of our meetings the group decided to talk about suicide. Most of the people in the group were young, in their late teens and twenties. During the course of the discussion I was appalled to hear how many had considered suicide, and actually attempted it, and the ages at which they had made their attempts. On reflection, I should not have been surprised. I could do the mental sums working out what year it was when these attempts were made and recalling how homosexuality might have been handled in public debate at the time. I wondered how many others had been successful in their attempts. I also realized that another reason I was so affected was that this was the only occasion I had sat down in a group of gay and bisexual men to talk about suicide. Yet suicide lurks in the background of day-to-day life, surfacing regularly in the deaths of friends who, having reached adulthood, decide that the struggle to get there wasn’t worth it. Nevertheless, it is not only public controversies that might compel a person to commit suicide. We live in a society in which a paramountcy of value is assigned to the heterosexual over the homo/bi/sexual. This heterosexual paramountcy is unchallenged everywhere and underlies the everyday routine of life – a fact behind Geoff Parkes’ painful question,

What happens to those of us who are left behind, swept under the carpet, pushed into our hiding places by a society that appears to believe that one’s greatest chance of fulfilment lies in a middle-class suburb on a Sunday afternoon with partner, kids and four-wheel drive in tow?’ (http://www.remyforum.net/geoff/gsuicide3.htm).

He then continues:

I survived a childhood that was filled with neglect, pain, alcoholism and religious intolerance, often unintentional but nevertheless, deeply disturbing; I survived Catholic education, and yet I’m still recovering, still burning with the anger at what the bastards inflicted on me for seven years straight; I even survived Toowoomba. I am alive. But I am not unique, or extraordinary because of this (http://www.remyforum.net/geoff/gsuicide3.htm).

Part of why Geoff does not consider himself unique or extraordinary is that the problem is not just Catholic schools or even Toowoomba. This heterosexual paramountcy is not neutral or passive in its effect. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick points out,

The number of persons or institutions by whom the existence of gay people – never mind the existence of more gay people – is treated as a precious desideratum, a needed condition of life, is small, even compared to those who may wish for the dignified treatment of any gay people who happen already to exist…the scope of institutions whose programmatic undertaking is to prevent the development of gay people is unimaginably large. No major institutionalized discourse offers a firm resistance to that undertaking; in the United States…most sites of the state, the military, education, law, penal institutions, the church, medicine, mass culture, and the mental health industries enforce it all but unquestioningly, and with little hesitation at even the recourse to invasive violence (1994: 42).

The heterosexual paramountcy actively strives to enforce uniformity and abhors sexual plurality.

If biblical studies can be considered a major institutionalized discourse then it certainly belongs in Sedgwick’s list. Biblical studies has participated fully in sustaining the regimes of compulsory heterosexuality responsible for so much suffering and death. The biblical texts themselves have long been employed as the ideological basis of such regimes. They have been twisted and braided to form the nooses that have choked out many a life. It is my consciousness of that fact that caused me to write this book to help unravel some of those lethal braids and loops. In so doing, I hope that I can help facilitate more queer people to Take Back the Word (Goss and West 2000) such that biblical studies might one day become an institutionalized discourse that celebrates the existence of queer people and works to encourage our increased presence and participation.

2. Reception, Intertextuality, Readers and Politics

That such a possibility might arise is assisted by the fact that, as Ken Stone notes, the discipline of contemporary biblical studies has been ‘undergoing a rapid transformation…with the appearance of a range of new interpretative questions and types of reading’ (Stone 2001: 11). While Stone adds that this process happened over ‘the last few decades’, it has most notably taken place in the last two decades. One of these transformations has been a shift in biblical studies to what Morris calls ‘post-critical exegesis’ (Morris 1992: 27) This way of reading links current literary strategies with both the critical biblical studies of the last 150 years and the pre-critical studies that preceded it. This new field is also known as the study of biblical reception. Thus, there have been studies such as Jeremy Cohen’s on the reception of Gen. 1.28 in early and medieval Rabbinic and Christian thought (1989) and anthologies such as A Walk in the Garden (Morris and Sawyer 1992) which sketched a history of images of Eden, Adam and Eve and the Fall. John Sawyer (1996) has written a study on the role of the book of Isaiah in Christianity. Marina Warner (1995) contributed an essay discussing images of the Queen of Sheba in Islamic, Ethiopian and European art and literature to an anthology of women writing on the Bible. Norman Cohn (1996) has also written on Noah’s flood in western thought. Most recently, Yvonne Sherwood (2000) has written a study of the reception of the book of Jonah in Christian and Jewish traditions. However, as if to show that there is nothing new under the sun, it is necessary to also cite Jack P. Lewis’ 1968 study of the interpretation of Noah and the Flood in early Jewish and Christian literature which anticipated the current interest in biblical reception.

Previously, biblical studies had been dominated by the historical-critical method, which aimed at ascertaining the meaning of biblical texts in the context of their own historical, cultural setting. Its quest was to discover the intentions of the authors of the biblical texts and to reconstruct that historical setting. Historical criticism was a quest for ancient Israel and its religion and so dismissed pre-critical exegesis in both Christian and Jewish traditions, not to mention the broader use of biblical texts in Jewish and Christian cultures. But the results of archaeology in Israel/Palestine have challenged the reconstructions of ancient Israel developed in critical biblical scholarship. Biblical texts are no longer confidently seen as windows into the past, and ancient Israel is now understood to be a shadowy world only glimpsed, ‘as through a glass darkly’, in the biblical texts. A darkened glass serves better as a mirror than a window, and so the world of ancient Israel, found by historical critics in the texts, turns out to be in large measure the world of the historical critical readers themselves, their assumptions and ideologies, not an objective, historical entity.

This changing understanding has led biblical scholars to adopt new approaches to biblical study, in particular to draw on literary theory to read the biblical texts as literature rather than history. The new interest in biblical reception has been aided by the development in literary theory of the concept of intertextuality as a tool for interpreting texts. The concept of intertextuality recognizes that texts do not exist in isolation but are always in relation with one another:

…any text is a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another. The notion of intertextuality replaces that of inter-subjectivity, and poetic language is read as at least double (Kristeva, cited in Carroll 1993: 57).

Texts echo and allude to each other. Similarities and differences between texts both invite ‘conversation’ between them and allow ‘each text to be affected by the other’ (Fewell 1992: 13). Every text has a pre-text, the texts that existed before it came into being, and a post-text, those texts subsequently generated by the text. A text is both a pre-text and a post-text of another. The post-texts of a text shape the pre-text that a reader brings to that text and employs in reading that text. Consequently, Penchansky gives three broad meanings of text by which an intertextual approach can be applied. First, there is the text itself, which an intertextual approach regards as existing in a relationship of juxtaposed texts. Second, there is the social text, the cultural conditions in which a text is read (Bal describes this as the pre-text, ‘the historical, biographical and ideological reality from which the text emerges’ [Bal 1989b: 14]). Finally, there is the interpretive text, the interaction of interpreters and audience with texts to create something new (Penchansky 1992: 77-78). The role of the reader is crucial in this process. Beal points out that it is the reader’s ideology that determines the legitimacy of intertextual relationships and how to ‘rightly’ negotiate those relationships (Beal 1992: 28). The reader alone can set the boundaries of texts and establish textual relationships.

The study of biblical reception illustrates the processes of intertextuality, through what Carroll calls ‘the discombobulations brought about by time’ (Carroll 1992: 68) of the biblical text. Carroll reminds us that:

Different theoretical perspectives inevitably produce very different readings of texts, and texts as traditional and ideological as the Bible are always vulnerable to changing paradigms of interpretation (Carroll 1992: 84).

Or, as Paul Hallam complains, ‘…the more I read the commentaries, the more they all seem like autobiographies, albeit disguised’ (Hallam 1993: 84). The biblical text is actually fraught with ‘obscurity’ (Handelman 1982: 29). It does not describe motivations or even the physical appearance of its characters. It is a text filled with gaps that create obscurity. Readers negotiate these gaps by filling them according to a regnant ideology, making ‘the interpretive act…similar to the creative act’ (Zornberg 1996: xviii). Bal points out that, because of this obscurity, a biblical narrative easily becomes an ideo-story, a narrative, taken out of context, ‘whose structure lends itself to be the receptacle of different ideologies’ (Bal 1988: 11). The study of reception helps to illuminate this process and sheds light on us as readers. Finally, the cumulative process of reading and interpretation, the post-text of the biblical texts, shapes the pre-text, which a reader employs in any interpretation of the biblical text. The biblical texts are also sacred texts to a variety of religions and cultures, so it is inevitable that there have been many different readings. The study of reception rediscovers those readings, either rejected or marginalized, and enables them to challenge the assumptions of the dominant pre-text. Thus, the study of reception can be a political process, which makes it well-suited to a project of anti-homophobic inquiry in a way that the old historical approach could not encourage.

3. Introducing Sodom and Gibeah

The story of Sodom is an ideo-story that has served to entrench homophobia and is still used for that purpose in conservative Christianity. However, the story in Genesis 19 is very much full of gaps. We are not told the nature of the evil of the city. There is no description of the Sodomites. The only indication we have of their character is the siege of Lot’s house by the men of the city, demanding that Lot’s guests be brought out to be ‘known’ by them. When Lot remonstrates with the mob, he nowhere makes plain how he understands their intentions. The rest of the story tells us no more than the fate of Lot and his family and the destruction of the city. Yet, when John Huston portrayed the story of Sodom in his film, The Bible…In the Beginning, Sodom appeared as a city almost taken over by a lesbian and gay Mardi Gras. The men of Sodom are shown as queeny, campy types, definitely not manly. Their speech is sibilant, they wear make-up, they are effeminate and they are predatory. Huston filled in the textual gaps so as to present the city as a hothouse of homosexuality, something not found in the biblical text. The political ramifications of this portrayal are best illustrated by my own experience. I first saw the film as a teenager wrestling with my sexuality, in the days before Stonewall. It was the first representation I had seen of homosexuality and, with its lethal consequences, was very much a text of terror for me. As the film has been subsequently regularly televised, I wonder how many other people, like myself, first saw their sexuality represented in that deadly way. I also wonder how many straight people had their homophobia reinforced by this film. My experience illustrates the political nature of many biblical texts and their subsequent representations.

Huston’s film also shows how texts are read, reread, even rewritten, in the development of a post-text, which is ‘any rewriting of a previous text, which is always a reading, be it a commentary or a different version’ (Bal 1988: 254). The post-text of Sodom and Gomorrah is an ongoing process of commentary, exegesis, midrash and representation, starting within the Hebrew Bible and continuing with apocrypha, pseudepigrapha, Christian scripture and onward with Christian, Jewish and other readings and representations of the story right through to modern times. Huston’s film is part of a homophobic post-text of Sodom and Gomorrah that homosexualizes the story and forms the dominant pre-text used today in reading the biblical text (the ante-text).

Turning from film to commentary, it is instructive to examine both the use of the homophobic interpretation in Robert Alter’s reading of Sodom and its uncritical acceptance, in my view, by the queer theorist, Jonathan Goldberg. Alter reads the story in the light of the promises of posterity to Abraham. For Alter, Sodom stands as a type of anti-civilization which serves as a warning of the precariousness of national existence and procreation which must depend on ‘the creation of a just society’ (Alter 1994: 32). Of the attempted rape of the angels, Alter declares:

…in regard to this episode’s place in the larger story of progeny for Abraham, it is surely important that homosexuality is a necessarily sterile form of sexual intercourse, as though the proclivities of the Sodomites answered biologically to their utter indifference to the moral prerequisites for survival (Alter 1994: 33).

Although Goldberg questions this incompatibility of nationhood and same-sex relations (Goldberg 1994: 6), he nevertheless accepts the validity of Alter’s reading of the story and includes it as the first essay in his anthology, Reclaiming Sodom, dealing with homosexuality and American culture. However, in part 3 of his Sodometries: Renaissance Texts and Modern Sexualities (1992), Goldberg explored the fear of ‘sodomy’ and its interplay with the precariousness of survival in early American colonial experience, especially that of the Puritan colonists in American New England. One could ask, therefore, whether Alter’s reading is a natural reading of the story or whether he replays an ongoing white American (male) anxiety. Hallam’s observation on commentaries is appropriate here, ‘(t)oo much autobiography…(e)veryone so certain they’ve been there, seen Sodom’ (Hallam 1993: 84).

Bailey, McNeill, Horner and Boswell, however, have all challenged the homophobic interpretation of Sodom and Gomorrah. Bailey and McNeill argue that the crime of Sodom should be understood as inhospitality towards strangers (Bailey 1955: 5; McNeill 1977: 45). Horner and Boswell argue that the crime should be understood as one of attempted rape of strangers (Horner 1978: 51; Boswell 1980: 93) something very different to consensual homosexuality. Additionally, Bailey and Boswell point out that the homophobic reading of Sodom and Gomorrah has never been the only way the story has been read. In particular, Rabbinic Judaism has never read the story as divine punishment of homosexuality. These arguments were reprised by Nancy Wilson (1995).

Acceptance of the homophobic interpretation of the story has never been an issue in critical scholarship. While individual authors are too many to enumerate, it was uncritically accepted and only in the last two decades does it appear to have been quietly dropped. With the exception of Simon Parker (1991), I have yet to find evidence that, until the early 1990s, any biblical scholar had ever publicly questioned the homophobic interpretation, which is still promoted by religious conservatives. Parker aside, of the five people mentioned here who have challenged it, McNeill, Horner and Boswell are all self-identified gay men and Nancy Wilson is both a lesbian and a minister in the queer inclusive Metropolitan Community Church. All five are outside the guild of biblical scholarship. In fact, it is only in the second half of the 1990s that visibly queer hermeneutical approaches have emerged within the discipline known as biblical studies. It is sobering to reflect that the landmark Postmodern Bible (Bible and Culture Collective 1995) had nothing to say about lesbian and gay hermeneutics, let alone queer, bisexual or transgender hermeneutics. It is also ironic, because any queer person of faith in the biblical religions must, ipso facto, be a skilled biblical interpreter if they are to survive in their traditions and at the same time validate their own sexuality/gender identity.

An intertextual approach to reading texts establishes textual relationships through the similarities, echoes and allusions that the reader establishes for one text with an/other/s. It is not difficult to establish an intertextual relationship for Genesis 19 because there is a remarkably similar story to that of Sodom in the Bible, the outrage at Gibeah recounted in Judges 19–21. Here, a Levite and his concubine spend the night in the town of Gibeah. As with the Sodom story, the house in which they stay is besieged by the men of the town, making the same demands as the men of Sodom. In this story, however, there is no divine intervention. Instead the Levite throws his concubine to the mob who rape her to death. The Levite leaves the next day and incites Israel to engage in a punitive war against Gibeah and the tribe of Benjamin. Thus, Gibeah is destroyed. This particular story remains a ghost haunting the cities of the plain. Its political significance lies in the fact that we have the words ‘sodomy’ and ‘sodomite’ to refer especially to male homosexuality, but not ‘gibeathy’ and ‘gibeathite’. The story does not form part of the homophobic pre-text, in which the biblical texts are used against homosexuality today.

It is also striking that t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introducing Sodom/olog/y: A Homosexual Reading Hetero-Textuality

- Chapter 2 Reading Sodom and Gibeah

- Chapter 3 A Shared Heritage - Sodom and Gibeah in Temple Times

- Chapter 4 But the Men of Sodom Were Worse than the Men of Gibeah for the Men of Gibeah Only Wanted Sex: Sodom the Cruel, Gibeah and Rabbinic Judaism

- Chapter 5 Towards Sodomy: Sodom and Gibeah in the Christian Ecumen

- Chapter 6 The Sin that Arrogantly Proclaims Itself: Inventing Sodomy in Medieval Christendom

- Chapter 7 Conclusion: Detoxifying Sodom and Gomorrah

- Bibliography

- Index of References

- index of Authors