![]()

An Interview with Giannalberto Bendazzi

“It is the World, Which is within the Head of the Artist”: A Closer Look at the History of Animated Adaptations

Figure 1.1: Giannalberto Bendazzi (2016).

Giannalberto Bendazzi is an internationally renowned film critic and historian and has been studying animation since his late teens. In 1980, Bendazzi was one of the founding members of the Society for Animation Studies, the leading association for scholarly investigations into the field. As a result of his decades-long journey, Bendazzi must be seen as possibly the most important animation scholar of the past three decades: In 1994, he published Cartoons: 100 Years of Cinema Animation, a history of the medium that has been translated into several languages. Bendazzi relied on personal interviews and meticulously conducted research to create a comprehensive world map of animation for the very first time. This challenged prevailing notions that saw animation almost exclusively as a medium that flourished and emerged in North America. He was looking deeply into previously under-researched regions and countries such as China, Russia, Africa, and Latin America and uncovering many unknown artists and their work.

His book also widened the angle of research substantially beyond an investigation of commercial (American) mainstream animation by focusing equally on independent animation worldwide and its masters. T. Lindvall stated about the book (1995): “Its scholarly breadth, richness, and attention to detail, along with its amazingly readable and engaging narrative, make this the most indispensable text on world animation history. Enthusiastically recommended as both a fascinating story and an incredible reference resource for both scholars and aficionados of the art of film.”

Since then, Bendazzi had continued his tireless investigative journey into the ever-expanding universe of world animation. He published more articles and books, for example, an edited tome about the Russian master Alexeieff (2001). But, in 2016, what must be seen as his crowning career achievement finally emerged: Animation: A World History, Vols. 1–3, a vastly expanded and revised continuation of his revolutionary 1994 book that brings the story up to date.

We are looking at no less than the most comprehensive chronicle of world animation ever published, unrivaled in its depth, accuracy, and sheer volume. It is also an indispensable resource to track the myriad changes that have come with the digital revolution that occurred almost precisely during the last 30 years.

What always made Giannalberto Bendazzi’s research stand out to the author is his keen interest in the artistic creation process and his ability to understand it and write about it in the most engaging way possible. Instead of relying on implausible speculation, he always went to the source—be it the artists themselves, co-workers, or production materials—to substantiate his findings with hard facts. Who else then would be a better qualified person to start this book with a deeper look into the concept of animated adaptations?

The following interview was conducted at Prof. Bendazzi’s office at Nanyang Technological University on November 18, 2014.

Hannes Rall (interviewer)

Giannalberto Bendazzi (interviewed)

Dear Giannalberto, we have come together to talk a little bit about adaptation for animation.

Adaptation, literary adaptation.

Yes, adapting literature for animation and what the specific requirements, if any, would be. Starting with my first question: Basically, I believe the history of animation is also very much a history of adaptation, because, from the earliest days on, fairy tales, myths, and legends have been adapted for animation, for example, by Disney. And these are often modified for the adaptation. Can you elaborate about that, about the historical developments? What I am particularly interested in is how the European fairy tales are changed for American adaptation.

The history of cinema in itself is a history of adaptations. So, it is not strange that animation followed. The first European animated feature film was made in Germany in 1926, and it was The Adventures of Prince Achmed by Lotte Reiniger; it was an adaptation from the 1001 Arabian Nights (Anonymous 2002).

Figure 1.2: Film still from The Adventures of Prince Achmed. © Christel Strobel, Agency for Primrose Film Productions, Munich.

Of course, in 1937, Walt Disney made Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (dir. Hand), which was an adaptation from the old fable; the most famous version had been the one by the Grimm brothers. But the adaptation, as such, is the normal approach. You take an idea, you remake it for the tastes of the audience, be it European or Northern American, or both, and you create a new thing. I make a difference between adaptation and illustration, because in many cases, you have short films that are made as adaptations from literary text, short novels, or poems. Of course, the adaptation involves a lot of creativity from the part of the adapter. And it is not strange that the Disney style overcomes the original story, because the main difference between the Grimm brothers’ Snow White and the Disney film is that each of the seven dwarfs in the film has a special character, and in a way, they carry on the film; they are the most interesting characters. While in the original story, they are a bunch of people without a special name. There is no point discussing the “authenticity” of this fairy tale, because there are at least 50 different versions that have been handed down through generations; it is a very often told and changed story. The adaptation is important, because for the market, the well-known title is a guarantee of success. And this is the main reason why the adaptations are so favored in Hollywood. Also, they are the guarantee for the public that they will not hear or see the same old story. They will be surprised. So, there is this double guarantee of success.

Figure 1.3: European illustrations from the late nineteenth century by the German illustrator Alexander Spitz (date unknown) and Swedish artist Jenny Nystrøm (ca. 1890). They are examples of a stylistic tradition, which also becomes evident in Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

With Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, you mentioned the importance to create seven very individual characters for the dwarfs, as a crucial ingredient for the success of the animated adaptation. A recent filmic adaptation comes to mind: The Hobbit film series by Peter Jackson (2012–2014). There was the challenge to individualize Bilbo’s (Martin Freeman) 13 different travel companions, which turned out to be a huge problem. Ishaan Tharoor categorizes them as “a baker’s dozen of dwarfs, who amble along in Tolkien’s narrative with little individual distinction” (2012). In comparison, the individual characters of seven dwarfs were a huge success and worked out very well in the Disney adaptation of Snow White. I don’t know how familiar you are with The Hobbit films, but it would be interesting to examine this problem further: Why did Jackson (arguably) fail, while Disney succeeded? Is it because of the sheer number of dwarfs you have to deal with? Or is the reason inherent to the adapted source material? In the original J.R.R. Tolkien book, the dwarfs are more treated as an almost anonymous group, with the notable exception of their leader Thorin Oakenshield. Disney applied a similar change compared to the source fairy tale, but he seemingly fared better.

In my opinion, the problem in this case is caused by the audience. The market has an audience, or the audience has a market. Peter Jackson is addressing his film to people who love the original book and to people who protect the original book, through constantly ongoing (online) communication. It has become a myth in our society, in our current society. So, the less Jacksonian the film is, the better it serves to save his box office results. While Disney had no comparison to make, he was free, because the story was nobody’s story. It was a legend more than a fairy tale. So, he could do whatever he wanted and whatever he did to the story was a (welcome) addition; it was something more; it was a gift for the viewers.

Peter Jackson, in some instances, seems to be actually more artistically successful in his The Hobbit series, when he moves away from the original Tolkien text. On the other hand, some of the decisions he made, like trying to individualize 13 different (dwarf) characters, were, in my opinion, just not working out narratively.

The Hobbit was much more difficult to make than The Lord of the Rings, because The Lord of the Rings is so vast that you can do without a lot of the things. The Hobbit is shorter, and you are like in a cage.

Yes, that makes it more difficult. An interesting aspect of adaptation is also that almost every adaptation (or many adaptations) would already qualify as a parody in some ways. But then there is, of course, the deliberate parody in itself as a spoof of the original. One of the most interesting examples to consider in that respect would be What’s Opera, Doc? (Jones 1957), because it is obviously a parody, a spoof, and then, it is simultaneously a very abridged version of the second part of Richard Wagner’s Ring der Nibelungen cycle, Die Walküre (1870). But I find that parts of it obviously also are really a lovingly created homage to the original source material. So, it would be good to have your thoughts about it, about that specific film, and about the relation to the topic of Wagner, of all things.

I hope you will be forgiving me, but in my opinion, cinema is a bourgeois means of…

Please feel free to say whatever you think about it…

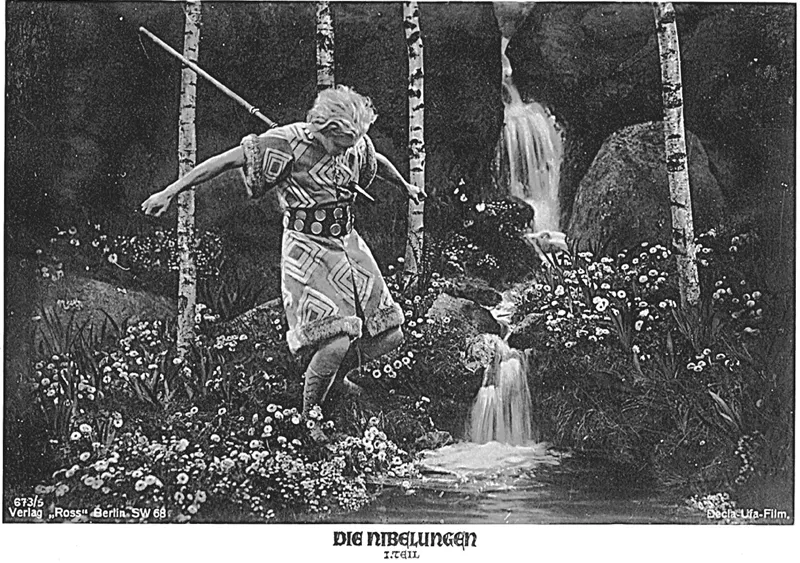

It is for the middle class. Even Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein 1925) is not a truly epic film. So, in my opinion, every film adaptation or animation that has been trying to transform an epic story into an epic film was a failure or, even worse, an unwanted parody. I think of, for instance, of Fritz Lang’s version of the Nibelungen (1924a and 1924b). It is ridiculous, because the Nibelungen are a fairy tale, are a legend; the Nibelungen are not human. The Nibelungen are ghosts, are semi-gods. Siegfried cannot look like a young blond man; Siegfried is the idea of the young blond man. I could say the same of Murnau’s Faust. I know that I am on the edge of blasphemy here…

Figure 1.4: Fritz Lang. Siegfried’s death. Publicity still for Die Nibelungen I (1924). Circa 1924. German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

No, these opinions are very welcome because they add to the discussion; that is important.

I don’t love Fritz Lang’s Nibelungen, but I love Murnau’s Faust (1926) a lot by the way. So, my answer is that it is impossible to make something else other than a parody out of an epic story, in our age and in our medium. You cannot even imagine a smaller and non-Hollywood production to do something like that.

But what I was trying to get to was that What’s Opera, Doc? goes beyond a conventional spoof or parody: It actually not only evokes laughter and amusement in the audience, but through the very powerful combination of layout, staging, and colors in the film, it also creates real drama.

This is the point. What makes What’s Opera, Doc? a masterpiece is ...