Language in all its varieties and forms is the most unique characteristic of all that defines our species. Of all creatures we alone have the ability to connect with others of our species so completely that we can communicate our most intimate feelings and thoughts, share in the experience of others vicariously, and reason in complex ways—and all this is possible because we have language. Furthermore each of us individually and collectively has the ability to create or invent language and modify it to serve our changing personal and social needs.

Language: Our Most Human Characteristic

No parent can help but be delighted and amazed at the universal ability of infants to begin to speak and understand the language or languages around them. They accomplish this at such a tender age that some scholars have come to believe that language isn’t learned, but rather is innate. We believe that what is innate in our single human species is the ability to think symbolically and create language.

Language, we believe, is a personal and social invention. Three human characteristics make language possible: first, we are social beings who cannot survive or live a full life without complex connections to each other. And second, we think symbolically: that is, we let complex abstract systems of sounds, scribbles, or motions represent our meanings. And, of course, we are an intelligent species. What would be the point of having language if we didn’t have things to say to each other?

Language is so marvelous that it leads to two rather opposite common views. One is that language is just there. We all come to use at least one of its many varieties without much thought about how or why this happens. The other is that language is itself an inscrutable mystery. And it is true no one theory or system has yet been produced by linguists that can fully describe or account for all aspects of even a single language.

Reading Is Language

This book is about reading. And because reading is a language process it is also about language. Since our species has the ability to invent new forms of language as our need and ability to connect with each other expands, both individuals and societies usually begin with oral language. Oral language serves the purposes of face-to-face communication. It is spoken and heard. As our need to connect becomes more complex—when we need to connect over time and/or space—written language is developed. For most hearing people, oral language is the first form of language to develop. But the ability to create language is not limited to speech. Deaf people can connect through manual signs and blind people can read through touch.

Our human need to connect is so strong that we have extended both oral and written language through digital technology. Oral language can be broadcast over distance and preserved over time so it overlaps the functions of written language. And digital writing on computers and cell phones can provide instantaneous dialog. Language multiplies human intelligence as we can think together and build on each other’s insights. Stored language expands human memory and the reach of our voices over great distances and over time. It connects us and fills our libraries and now our cyberspace. Truly, technology has made it possible to put the wisdom of the ages at the fingertips of each of us, all represented in language. Our ability to use symbolic representation is not confined to language. We assign significance to objects, numbers, dates, colors—almost anything. And we can express emotions and concepts through music, art, and dance.

Once we are comfortable users of a language we have the sense of dealing directly with meaning with little conscious thought, most of the time, to how we are accomplishing that. In this book we intend to make you aware of what you are actually doing as you make sense of written language. Reading is not inscrutable. But it is indeed marvelous. Some common-sense beliefs about how reading works are untrue, as is often the case of the things we do so often without thinking about how we do what we do.

The Illusion of Reading Every Word

We will help you understand that one such popular belief is that when you read you are recognizing the words on the page from left to right as they are printed.

It is likly that you think your seeing every word now as you reed this book. You you may find it hard to except the idea that you could of missed noticing some vary obvous typos. A side from that, the idea that accurate reading is an illusion maybe strange considering most of us were taught that accurate reading is necessary four comprehension.

To understand how we make sense of print you need to understand that the idea that you read every word is an illusion. We call it a “grand illusion” because it is so important in understanding what reading is and how it is learned and taught. You may have thought you saw a misprint in the paragraph above. Now please go back over that paragraph and count the number of errors we deliberately put there. How many did you find? None? 2? 6? 12? How many were there?

Have we teased you to find out how and why this happens? The grand illusion in reading is no clever magician’s trick. It goes to the heart of how our brains work to make sense not only of reading but of the world as we find our way around it.

Edmund Huey’s Challenge

In 1908 Edmund Huey wrote:

so to completely analyze what we do when we read would almost be the acme of a psychologist’s achievements, for it would be to describe very many of the most intricate workings of the human mind, as well as to unravel the tangled story of the most remarkable specific performance that civilization has learned in all its history.

(p. 6)

We dedicate this book to Edmund Huey as we share what we have learned about reading and the “most intricate workings of the human mind.”

Limitations of Our Senses and Illusions of the Human Brain

Illusions permeate our everyday mental life. Of course, we are not always aware of the illusion we are experiencing. In fact, the vast majority of illusions go undetected. Still, a natural curiosity takes over; we often feel satisfied only if we make sense of the illusion, and we may be bothered by failing to understand it. Why did I think one thing when the reality was something else altogether?

This dilemma is precisely the key to understanding illusions. The very fact that illusions exist, that they generally go undetected, reveals how the brain’s various psychological mechanisms work collaboratively to make sense of the world. In doing so, accurate perception may be sacrificed for the preferred sensation of having made sense.

Illusions Arise from Distinct Sources

Countless illusions are rooted in the simple biological fact that our sensory organs—those collections of cells that allow us to detect light and color and sound and physical texture—are far less complete in their detail than the world they are trying to detect. Human eyes can only detect light within a certain range of wave length. They do not have the resolution capacity of pit vipers in detecting infrared, for example. The ears can only detect sounds within a certain frequency range. They do not have the resolution capacity of our canine companions. We certainly lack dogs’ acute sense of smell. As the renowned neurologist V.S. Ramachandran (2004) has stated: “We need to construct useful, virtual reality simulations of the world that we can act on” (Ramachandran, 2004: 105). In other words we use our incomplete sensory information to construct an illusory world that is (usually) sufficiently accurate that we can act on it.

The Blind Spot Illusion

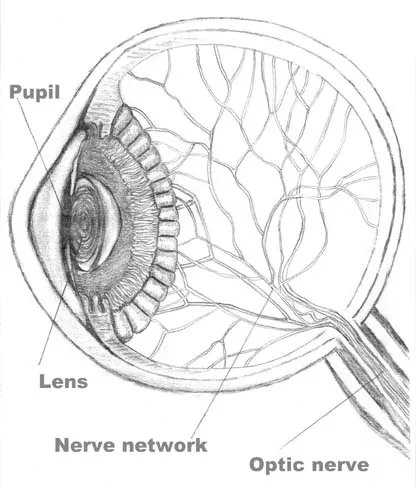

The eye contains layers of nerve cells that detect electromagnetic radiation that corresponds to the colors of the spectrum. These retinal cells line the back of the eye, each one sending along the visual information it has detected to a central meeting point also in the back of the eye. Imagine photodetectors completely covering the surface of a wall, each with a long wire headed toward a hole in the middle of the wall, with all the wires meeting at that hole and diving into it to deliver their information to the next relay station.

Figure 1.1 The Human Eye. Original art by Shoshana Pearson

Only one spot on the wall contains no photoreceptor, and that is the spot where the hole is. For the retina, a similar hole exists where the nerve wires meet as they continue their journey all together to the next relay station in the brain. Therefore, any light that lands only on the area of the hole goes undetected. The visual picture created by the merging together of the retinal information contains a blind spot right in the middle of the visual field. Sophisticated studies have demonstrated that the brain “fills in” the blind spot.

That is worth emphasizing—the brain, not the eye itself, fills in the blind spot. And it fills it in such a way that there appears to be a seamless continuity between that part of the visual picture constructed from actual electromagnetic input and that part projected onto the picture by the brain itself. Therefore, what we perceive is the illusion of a scene determined entirely by the world outside us, by what we are looking at. In truth, a piece of that scene was patched in by the brain.

There is a functional advantage in the construction of a visual scene that makes sense because of its consistency, as opposed to one that does not make sense because we don’t really believe that the person we are looking at has a hole in his forehead.

Away From and Toward Reality

Sometimes illusions move away from objective reality as you did when you read and missed some of the errors in the paragraph on page 3. The blind spot illusion abstracts toward reality, and creates a perceptual visual scene that is actually a truer representation of the objective world.

But despite the quite opposite character of these illusions, they are united in a common feature: they construct mental representations that make sense within a specific context and that permit efficient and effective transactions within that context.

Illusion, in other words, is created in the normal and natural course of the brain’s transaction with the world and the limitations of our sensory equipment to accurately represent it. What matters, though, is not the degree of accuracy of the sensory equipment, but rather that the brain can make sense of the sensory information detected, however limited or distorted it may be.

As we have just observed, perception is only partly accurate. Many true aspects of the objective world are detected, but most are ignored. Experienced drivers can focus on the small red or green light in an intersection that tells them to stop or go and ignore all the other lights and signs. We even distort those aspects we do detect, as when we perceive a uniform shade of green in a landscape with many different shades of green. We believe that we have perceived accurately, even when we haven’t. One role of science is to investigate the mismatches between the real world and what we have come to believe about it both individually and socially.

Accurate Perception Is an Illusion

Even more intriguing is that what creates the illusion of accurate perception is having made sense of the visual, auditory, or tactile scene. When making sense fails, we simultaneously conclude that what we thought was an accurate perception of the world was in fact quite inaccurate. We do not, of course, rest at the realization of inaccuracy in our perception. We take the new information and construct a new interpretation, one that now makes better sense. That’s what we will demonstrate happens in reading. That’s what happens in life.

But, you might ask, haven’t we just admitted that even though we thought we did, we didn’t really make sense of the scene? This is a very important question. For it is quite true that just because we think we have made sense, our hypothetical little mini-theory of a visual scene may turn out to have been wrong. Or we may have used faulty logic in making sense without realizing it. Or we may have used a false premise in our sense-making reasoning. For any number of reasons, the sense we construct may, in fact, be nonsense or in...