![]()

Following the Second World War, Switzerland was in the very fortunate position of having been spared the destruction of a brutal European war. Postwar, the country had no imperative to rebuild bombed cities, but could, after years of scarce resources, commit to economic recovery and the building of new infrastructures. The biggest challenge was the housing shortage in the towns and cities, caused by the influx of people from rural areas.

In the period before the 1960s, the country experienced an unprecedented economic boom and the building sector prospered. However, Swiss architecture found itself in a peculiar situation. During the isolation of the war years a particular Swiss regional style of architecture had emerged, which attracted strong European interest in the postwar years. Simultaneously, young Swiss architects, in order to escape the limitations of the regional style, looked to reconnect with international, especially American, modernism. In the 1950s, these young architects fought for the renewal of a corresponding Swiss modernism. Having achieved their cultural aspirations by returning to the legacy of the Swiss modern masters, they were however, accused of merely being epigones.

The celebrated ‘Swiss way’ and its limitations

The acceptance of modern architecture, or the Neues Bauen in Switzerland, had come late, but lasted longer than in most other European countries. Architects deliberately distanced themselves from the rhetoric of classicist state architectures identified with the dictatorships of neighbouring countries. Modern architecture was seen as resistance to the status quo, and a purely monumental architecture had never been representative of the bourgeois microstate that was nineteenth-century Switzerland. Clients and architects attached importance to sober and pragmatic construction in architecture, and avant-garde experiments remained the exception. In the 1930s, Swiss architects developed a consensus about the concept of a ‘moderate modernism’, which in 1939 found its culmination in the pavilions built for the federal exhibition in Zurich; affectionately known as ‘Landi’ (Landesausstellung). From then on the Landi-Stil was an established term. A traditional style with regional roots, a staid and plain minimalism derived from the simple building types of past master builders was developed in the context of the isolation and defensiveness prevalent during the war years. The building of settlements, the main preoccupation of the building industry, saw the reemergence of the nineteenth-century tenement block; with pitched roofs instead of flat roofs, punch-hole facades instead of horizontal long windows, brick and timber instead of concrete and steel, these simple forms could be built by local brick layers and carpenters in the villages.

After the end of the Second World War, the Swiss government swiftly and somewhat calculatingly responded to the interest in Swiss regionalism that surfaced in Europe. In September 1946, commissioned by the Swiss Federal Council, a number of different institutions presented the Switzerland – Planning and Building Exhibition at the RIBA in London.1 This, as the first major exhibition on Swiss architecture outside Switzerland, incorporated 600 posters and was also successfully shown in Copenhagen, Stockholm, Warsaw, Amsterdam and Cologne. In Switzerland the exhibition was covered extensively in Schweizerische Bauzeitung (Furrer, 1946), and briefly in Werk (Roth, 1946a). It was not available to a Swiss audience until January 1949, when it was shown in the Kunsthalle Basel.

Hans Hofmann, chief architect of the 1939 ‘Landi’, and professor of architecture at the Eidgenössische Polytechnikum in Zurich (ETH today), in his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, presented the architecture which had emerged in isolation from international tendencies as a logically consistent development of 1930s modernism: ‘We gratefully acknowledge that the Neues Bauen provided a fruitful basis for the development of a contemporary architecture. The break with tradition forced us to re-evaluate the fundamental problems of building and architecture’ (Hofmann, 1946, p. 136). Distancing himself immediately, however, he argued:

For Hofmann, the development during the war was to be seen as a corrective, maturing and complementing the principles of Neues Bauen:

Hofmann distinguishes between two stylistic categories, one traditional and the other modern:

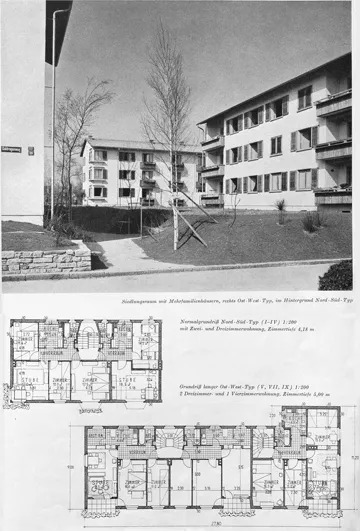

Two publications disseminated this regional style in Switzerland and abroad: Schweizer Architektur: Ein Überblick über das schweizerische Bauschaffen der Gegenwart, by the architect Hans Volkart, was published in Germany in 1951 (Volkart, 1951); in the same year in Switzerland, Der Siedlungsbau in der Schweiz, by the chief architect of Basel, Julius Maurizio, was published (Maurizio, 1951). Both books summed up the dominant organisational types and showed once again the contrast between traditional and modern building types. Urban Dörfli (housing estates), many of which emerged after 1940, stood in contrast to utilitarian buildings for industry, administration and infrastructure. Both categories diverged in their respective directions until the mid-1950s.

The folio publication Moderne Schweizer Architektur 1925–45, compiled by Max Bill (Bill, 1949), and republished in a second edition in 1949, provided a counterpart presenting exclusively ‘modern’ buildings, coupled with a plea for architects to dare again to build modern architecture. While the official exhibition represented the built reality of this period, it only reflected a limited picture of architects’ current opinions. The younger generation was discontented, as it perceived the architecture of the wartime and the immediately postwar years as traditional and petty bourgeois. In the decade following 1945, this generation began to rediscover, after years of isolation and via the newly available (again) international architecture journals, developments abroad. The architect and aspiring novelist Max Frisch, who had been invited by the Rockefeller Foundation to visit the USA in 1951, wrote, on his return to Switzerland, a sardonic account of Swiss architecture. Having presented this as a lecture to assembled colleagues of the BSA, who had developed the very building types he criticised, he proceeded to publish his attack in their journal Das Werk:

This conservative mentality was clearly getting on Frisch’s nerves:

He had experienced American cities, and the modernism developed during the war by European emigrés like Mies van der Rohe, Gropius, Neutra and Breuer. Mexico City, for example, in his view was an architectonic jungle, but one that contained orchids of modern architecture. In Switzerland, he believed, even an airport terminal would be compartmented to a degree that prevented any suggestion of monumentality. Everything had to be intimate and inconspicuous. Appalled, he insisted: ‘I am an urbanite, I am a renter and not a farmer living on his soil.’

Das Werk: mirror of discord post-1945

Das Werk, Schweizer Monatsschrift für Architektur, freie Kunst und angewandte Kunst, founded in 1914 by the Bund Schweizer Architekten (BSA) and the Schweizerische Werkbund, was for a significant period the most important publication for architecture and design in Switzerland. Its themed issues were published monthly and it was unusual in that it not only covered architecture, urban planning and garden design, but also interior architecture, art, design, graphic design and fashion. All these disciplines were given generous space, with a focus on developments in Switzerland. The respective editors-in-chief, overseeing the whole spectrum, would heavily shape the contents of the journals. It was only in 1943, with the inauguration of Alfred Roth, that a second editor would supervise the two art publications.2

Das Werk was originally founded by young BSA members primarily in order to establish a mouthpiece for their reform-oriented architecture, opposing the neo-Renaissance style of Swiss followers of Gottfried Semper. However, the federation’s publication was quickly confronted with the new tendencies of both neo-classicism and modernism. The editors were confronted by the strongly divergent positions of the BSA members, who all insisted on their right to see their work published. Moreover, they sought to influence developments with axiomatic texts. Which kind of architecture was to be the order of the day? Peter Meyer, editor from 1930 to 1942, who shaped the journal’s issues with his astute and sometimes polemical commentaries, tried to propagate a third ‘Swiss’ way, between classicism and modernism, while heavily condemning 1920s classicism, particularly that representative of the German, Italian and Russian states. He was also critical towards the Neues Bauen, in which he missed the aspect of monumentality, and the 1930s ‘moderate modernism’ that was, although acceptable, not the ideal which he tirelessly propagated in his journal. Shortly before his resignation he identified his conception of a modern monumentality in the building for the University of Miséricorde in Fri...