It is not always easy to sense how long an exercise should last. I have suggested an average duration for each one listed below; this includes time for feedback. I have found that in any game the group’s energy will drop after a fairly short time of playing. In an inexperienced group this drop will usually happen quite soon. The teacher will probably feel that this is the moment to stop and maybe go on to another activity, but if he has the courage to let the group continue to play on through those ‘dead’ moments, he will nearly always find that the energy rises again, this time with a new and fresher impetus, more invention, more team-playing and a sense that the activity now belongs to the group and will now continue until players are tired or till it comes to a natural conclusion. These exercises can be used more than once with a group. Once players know the rules they can become more skilful, have more fun and maybe invent new variations.

Many games involve working in pairs, but, if there is an uneven number in the group, three players can work together; in this case, the teacher may need to give the group of three a slightly different change-over signal, earlier than the signal for pairs, so that each player in the group of three can have a turn. If the exercise continues with new pairs a new group of three should be formed.

It is often useful to have time for feedback after an exercise; this gives the group a rest if they have been working hard and an opportunity to consider the purposes of the experience that they have just shared. I tell players that their effortless achievement in these exercises takes away all future excuses; that if they can do this then they can play the character in the scene.

Free Drawing

A quiet exercise. Most useful as a start to a class or rehearsal, also useful as a means to explore characters and relationships in a play. Works well with new groups and does not lose its power however many times it is experienced.

Recently, a student who works at a shoe shop each weekend in order to pay for her course told me that she had introduced free drawing to her fellow shop-assistants during a long afternoon with no customers. The girls enjoyed the game so much that they now turn to it whenever they have a free moment; it seems that the need to express feelings non-verbally and to allow oneself to play without aiming for a result can be satisfied with this simple exercise.

Focus: To naturally direct attention into creative action.

Laban aspect: Free Flow.

Space, time and numbers: Room for all players to sit and draw with their paper on the floor; can be brief, around 5 to 7 minutes, but can be extended; any number.

What you need: A sheet of paper, at least A4 size, for each player and plenty of colouring pens, crayons or pencils. A bin for the drawings that are torn up.

I find this exercise so valuable that I now start every class or rehearsal with 5 minutes of free drawing. Almost every group, no matter what age or stage they are at, enjoys it, finds it helpful and wishes to do it as a starter to every session. Quietly doodling / scribbling / drawing allows people to become calm, to arrive more completely in the room and to express their feelings at that moment. I have been surprised and delighted to find that the quality of the work and the atmosphere within the group are so much better after this brief experience. For myself, when I need to move from working with one group to working with another, or from my life outside the rehearsal room to the world of the scene, the 5 minutes of quiet focus with everyone in the group give me the clarity and presence I need to do good work.

On her way to one of my classes, a student had had angry words with a taxi driver. As she settled to draw, she had time to understand her hidden upset, to express it by scribbling black lines on paper and so to get rid of those unpleasant tensions, which enabled her to work freely and happily in the group.

For a different class I gave – a one-off workshop with young students, one group aged 8–11 and the other aged 12–18 – I had planned to do the drawing for around 5 to 10 minutes as usual, but once the kids had started to draw, it was clear that this was giving them a chance to express themselves and in the end the drawing continued for almost the whole 2-hour session. In this case the children wanted to show and explain their drawings to me, and that added to the time we spent on that one exercise. It was also important to tell them – and all groups – that they could tear up their drawings if they wished to. Young girls, drawing pictures and images of people who bullied them at school, needed then to destroy those images. With one group we all tore up our pictures, throwing the tiny pieces of paper up so that they fell like snow all over the floor. (Then, of course, we cleared them up together and put them in a bin!) In another group, a boy, rather small for his age, found it hard to start drawing; it was difficult for him to feel safe about expressing himself, so he needed to work privately and to be able to hide his first drawing after showing it to me; after this one, where he had drawn himself trapped behind prison bars, he went on to do many more, ending with several that showed him as a mountain.

When I started the work I experimented with the time limits, asking groups which suited them best: 5, 6, 7 minutes… up to 20 minutes. The consensus was that 7 was best for them. (This was with two separate groups of American actors doing a class on Shakespeare’s sonnets.) If the free drawing is used as a starting exercise it is best, I think, for the teacher to say ‘5 minutes’, then, at 5 minutes, to start to collect the pens and let people stop drawing within the next 2 or 3 minutes. Alternatively, the exercise can run as long as the energy lasts.

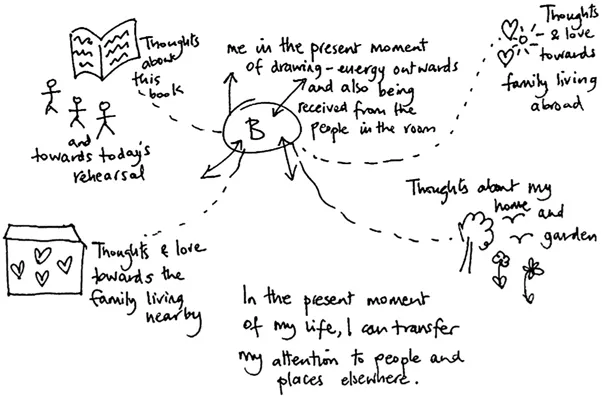

To introduce the idea, I do a 2-minute drawing myself, explaining as I go along and being truthful about what matters to me at that moment. So, I usually start with an image of the group and myself – maybe a circle with bright lines radiating out of it – then I could go on to scribbles of my home; absent family members who I am thinking of; my garden, if I want to be working in it after class; possibly money if I am concerned about that, etc. Each time is different and cannot be prepared. I use words too, if I want to.

Figure 1 Map of me: I made this diagram very quickly in a class with RADA students. It is better to use coloured pens. I have added the explanations for this book.

Using free drawing in rehearsal

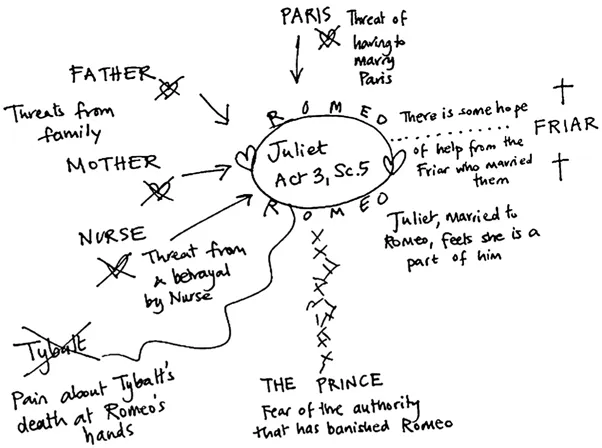

You can develop the exercise to explore characters’ backgrounds and their situations within the play. When I did this with a cast rehearsing Macbeth, the actor playing Macbeth drew a picture of his character, as he saw him, full of images from the play. We then began to draw other characters and, from there, to draw one character from the point of view of another, so ‘Macbeth’ drew ‘Duncan’; ‘Lady M’ drew her husband; ‘Duncan’ drew ‘Lady M’ and so on. We found this fun and useful and that it could be used as a practical way to build a character, using images found in the text. If you make time during rehearsals for quiet creative work like drawing you will find it a release from anxiety, a welcome change of rhythm and a gentle means of drawing your concentration in to the world of your character, which will provide the foundation of belief when you get up to play your scene. The drawing seems to release an inner understanding, free of judgement, enabling us to drop a bucket into what Stanislavsky calls the ‘creative subconscious’. This is the sense of play that we need and enjoy as actors.

Figure 2 Map of character: As the story changes, the character’s map must change. Using coloured pens is better.

Yes, and…

Focus: To explore problems of approach and shared energy in acting.

Laban aspect: Bound Flow into enjoying Free Flow.

Space, time and numbers: Anywhere; about 15 minutes; any number can play as long as people are working in pairs; players should change partners at each of the three stages so that they work with three different partners. Allow time after each stage for feedback.

This very helpful game comes via the work of Keith Johnstone,1 who found it in Viola Spolin’s Improvisation for the Theater.2 The uses of this simple game extend far beyond the first playing of it: many blocks and problems in acting and life can be recognised and dealt with by remembering how you felt during the two first stages of saying ‘no’ and ‘yes, but… ’ before moving onto the freedom of ‘yes, and… ’ The psychologist Raj Persaud calls these mental blockages ANTS: Automatic Negative Thoughts – a useful description.

Some time ago I made one New Year’s resolution which I have kept: I will not do anything which is not fun to do. Writing this is fun as I write it; when it stops being fun I will stop and play another game… maybe I’ll do the washing-up or read a book. If I can sustain my recognition of the autonomy I have, that is, know that I have the power to choose and take responsibility for my choices, then whatever I decide to do has that bubble of fun inside it. Are you already thinking of situations where the person has no choice? I heard a true story the other day about a Palestinian man held up at a border-crossing by an Israeli soldier who told him to strip to be searched. The Palestinian had a choice, although there was a gun pointing at him. He chose to refuse to strip and eventually the soldier let him pass. Both men made a free choice of action. We, in our relatively free society, have the daily privilege of choice: what to wear, where we live, what we eat, what we say and do; there is no excuse for us to hide behind the ‘mind-forged manacles’ as Blake calls them, of ‘I have to’; ‘it makes me feel like… ’; ‘I can’t help it’ and so on.

Stage one: Saying ‘No’

A makes offers to B that she hopes B will find hard to refuse; B just says ‘No’ to every offer made. This ‘No’ needs to be simple and unequivocal, just a calm, firm block to every suggestion from A.

Example:

A: would you like to star in a play at the National Theatre?

B: No.

A: What about a holiday on a beautiful island, all expenses paid?

B: No.

A: Would you like some chocolate?

B: No.

A: A cup of coffee?

B: No.

A: A million pounds?

B: No.

And so on.

The players then reverse roles, with B making the offers and A refusing them. This stage illustrates the frustration and deadening negativity of the actor who will not respond to her partner; it is not a problem that often appears openly but it can be used as protection or concealed attack. The offer represents our talent and creativity; the reply ‘No’ represents our fear.

Stage two: Saying ‘Yes, but… ’

This excuse is used when ‘the native hue of resolution is sicklied over with the pale cast of thought, and enterprises of great pitch and moment… lose the name of action’ (Hamlet, Act 3, Sc. 1). If we are honest we can all r...