![]()

Cluster 1

Ethics and values

![]()

Chapter 1

Examining early childhood education through the lens of education for sustainability

Revisioning rights

Julie Davis

Abstract

This chapter calls for rethinking of the rights base of early childhood education. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (UNICEF 1989) has been seen as an important foundation internationally for early childhood education practice. In this chapter, I argue that while the UNCRC (1989) still serves its aspirational purpose, it is an inadequate vehicle for enacting early childhood education in the twenty-first century given the pressing challenges of sustainability. The UNCRC emerged from an individual rights perspective, and despite attempts to broaden the rights agenda towards greater child participation and engagement, these approaches offer an inadequate response to global sustainability concerns. In this chapter, I propose a five dimensional approach to rights that acknowledges the fundamental rights of children as espoused in the UNCRC and the call for agentic rights as advocated more recently by early childhood academics and practitioners. Additionally, however, discussion of collective rights, intergenerational rights and bio/ecocentic rights are forwarded, offering an expanded way to think about rights with implications for how early childhood education is practised and researched.

Introduction

We live in times of uncertainty and insecurity where there are increasingly urgent calls for the world’s peoples to live more socially, economically and environmentally sustainable lives. UNICEF (2013) states, ‘it is increasingly recognized that a sustainable world will require a shift in values, awareness and practices in order to change our currently unsustainable patterns of consumption and production’ (p. 16). Education holds the key to the necessary shifts in thinking, values and practice required for these transitions (Sterling 2001, UNESCO 2005). Like all education sectors – indeed, all sectors of society – early education has a role to play in societies’ transitions to sustainability. This calls for a shift from ‘business as usual’ in early childhood education. Here, I propose a starting point for this shift is revisioning children’s rights, human rights and justice and how these concepts can be rethought for the challenges confronting humanity in the twenty-first century and beyond. At the core of my argument is that in early childhood education we currently conceptualize rights – as exemplified by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (1989) with its origins in the social practices of liberal democracies post-World War 2 – far too narrowly.

While the ambitious, but aspirational goals of the UNCRC are as important now as ever before, societies of the twenty-first century are vastly different from those that framed the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) and the UNCRC in the twentieth century. Socio-political, economic, and environmental dynamics have shifted dramatically. We live in a connected world with global movements of people and goods – made easier with the vibrancy, speed and ease of the Internet and social media. At the same time, the world appears to have become more fragmented and vulnerable with weakened economies, rising social tensions, uncontrolled human migrations, and fears about global pandemics and food security (Centre for Strategic and International Studies 2013). Such complex social, economic and environmental changes demand new responses from all sectors of society.

There has already been some reworking of the way children’s rights were originally constituted in the UNCRC; however, the UNCRC, like the UDHR (1948) from which it is derived, is largely constituted as individual child rights (UN Regional Information Centre for Western Europe 2012). While I acknowledge that there are other early childhood scholars and practitioners who have been working at reframing children’s rights, and discussing and problematizing participation rights for example, I propose a far wider conceptualization of rights, one that better meets the challenges of sustainable living now and for the future.

Why revise rights in early childhood education?

Education for sustainability is about creating changes in how we think, teach and learn; early childhood education has much to contribute to society’s transformations towards sustainability. The starting point is our fundamental values, focusing in on children’s rights, human rights and justice. My argument is not for any diminution of children’s rights or any lessening of the universalization of human rights across the globe; what I do argue for is augmentation of thinking about children’s/human rights if early childhood education is to make a lasting contribution for sustainability. Indeed, this chapter and the book, more broadly, is about elevating the rights of children as active citizens for sustainability (Johansson and Hagglund, Chapter 2). Consequently, just as there has been an evolution of children’s rights from ‘protection’ rights to children as ‘rights’ holders’, I argue for children as ‘rights’ partakers’ to become the new norm, and for rights to be radically extended to include collective rights, intergenerational rights and rights beyond those held by humans.

By implication, an augmented view of children’s rights asks that early childhood education be enacted differently. I contend that this challenges the current theories and pedagogies that prevail internationally in early childhood education – principally socio-cultural-historical approaches (e.g. Fleer 2010). I argue, instead, for eco-socio-cultural-historical and transformative theories and pedagogies to take early childhood education into the new territory that sustainability demands – similar to the proposal by Jickling (2013) who discusses a socio-constructivist/transformative education as a potential basis for Education for Sustainability (EfS). In so doing, I offer provocations and some possibilities for exploring how early childhood education might be enacted with an expanded rights framework.

What might an expanded rights framework look like?

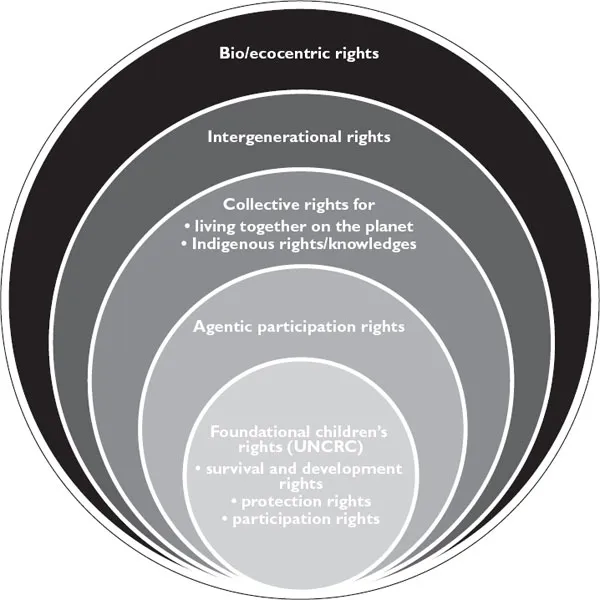

Prompted by the challenges of sustainability, I propose a revisioning of rights in early childhood education that brings new dimensions into play. These are outlined below and illustrated in Figure 1.1, as:

• foundational rights as promulgated by the UNCRC

• agentic participation rights

• collective rights

• intergenerational rights, and

• bio/ecocentric rights

Figure 1.1 Five dimensions of rights for early childhood education in light of the challenges of sustainability

Explaining the dimensions

Here, I elaborate on each of the dimensions illustrated above. The starting point, as already noted, is the foundational and aspirational view of children’s rights drawn from the UNCRC. The second dimension expands on child participation rights, but calls for active/agentic participation to be the norm. The third dimension explores collective rights as an addition to thinking about children’s/human rights. The fourth dimension considers intergenerational rights, while the fifth expands beyond human rights to give consideration to the rights of all living beings and the non-living attributes of nature/natural environments. It is important at the outset, however, to acknowledge that these dimensions are not mutually exclusive; they overlap and seep into each other. Boundaries can be envisaged more as permeable membranes rather than impermeable barriers. I contend, though, that all dimensions must be considered if sustainably is ever to be realized. While it is logical that educators will focus on what they see as the best for the individual children they work with here and now, I propose that one cannot choose to ignore their collective rights, the rights of marginalized groups, future children, or non-human species when thinking about children’s rights. There is no hierarchy or option associated with these dimensions, however, for elaboration purposes each dimension is addressed separately.

Dimension 1: supporting children’s rights as foundational

One response to the tragedies of World War 2 were international efforts to entrench peace, rights and freedoms which led to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The UDHR (1948) universally recognizes that basic rights and fundamental freedoms are inherent to all humans, apply equally to everyone, and that every person is born free and equal in dignity and rights. Recognized as the foundation of international human rights law, it led to a range of more focused international human rights treaties, covenants and conventions.

One elaboration was the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child (UNDRC), proclaimed in 1959, when world leaders determined that children and young people under 18 years of age required a special convention to protect them because of their perceived immaturity and potential vulnerability. This was later followed by the UNCRC (1989), the world’s most ratified human rights treaty that became the first legally-binding international instrument to incorporate a wide range of human rights for children – civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights. In so doing, the Convention went beyond protective rights (MacNaughton, Hughes and Smith 2008) in recognizing children as human rights holders and not simply having rights to protection. The UNCRC has become the basis for discussion and implementation of children’s rights within early childhood education around the globe (Bennett 2009, Sheridan and Pramling Samuelsson 2001).

The guiding principles of the Convention are encapsulated in 40 ‘articles’ that revolve around rights to life, survival and development; non-discrimination and protection; and participation rights (UNICEF 2005). These are summarized below.

Survival and development rights: These comprise rights to the resources, skills and contributions necessary for survival and full development, including rights to adequate food, shelter, clean water, formal education, primary health care, leisure, recreation and play, cultural activities and rights information.

Protection rights: These rights include protection from child abuse, neglect, exploitation and cruelty, including the right to special protection in times of war, and protection from abuse in the criminal justice system.

Participation rights: Participation rights include the right to express opinions, to have a say and to be heard in matters affecting their social, economic, religious, cultural and political life, the right to information, and freedom of association. Engaging in participation rights helps bring about the realization of all their rights and prepares children for an active role in society.

(UNICEF 2005)

To summarize, like many academics and practitioners in early childhood education, I identify the Convention as foundational to our work. I acknowledge, too, ongoing discussions (Bennett 2009, Coady 2008) that enable early childhood educators to rethink different meanings of the Convention and to engage reflexively. Continuing this tradition of rethinking, and in light of the challenges of sustainability, I now offer some new thoughts about children’s rights.

Dimension 2: recognizing children’s agentic participation rights

Participation rights as readiness/preparation for children’s active role in society is my starting point for discussion about Dimension 2. As noted above, having a voice, being heard/listened to, accessing information, and freedom of expression are fundamental rights constituted in the UNCRC. There are, however, two points for critique with this aspect of the Convention – one concerns images of children; the other relates to conceptualizations of active participation.

Regarding the first point, it is true that participation rights have been examined and rearticulated post-UNCRC (1989), to encompass issues of identity, autonomy, freedom of choice, expression of thoughts and views, and involvement in decision-making (Sheridan and Pramling Samuelsson 2001, Tomanovic 2000). Further, as MacNaughton, Hughes and Smith (2008) observe, contemporary research is now generating images of young children who:

• can construct and communicate valid meanings about the world and their place in it

• are capable social actors with a right to participate in our social, cultural and political worlds and to contribute valid and useful ideas

• know the world in alternative (not inferior) ways to adults

• have perspectives and insights that help adults better understand children’s experiences.

Such images are of children as visible, social, active players in their various contexts. Nevertheless, changing the imagery of children is not enough to ensure agentic participation, which brings me to my second point of critique. I argue that the UNCRC is not explicit enough about the types of active participation that are possible for young children. As Coady (2008) states, children may be ‘active’ in the psycho-social sense without being demonstrably expressive ‘social actors’, and they may be both psycho-socially active and social actors without necessarily being ‘agentic’ in the more political sense of significantly influencing their situation, or being listened to.

I argue that images of children’s participation – as well as images of children – also require reformulation as current conceptualizations and their attendant practices are outmoded for the dynamic, complex and challenging times in which we live. An Australian study about young peoples’ participation in climate change responses, for example, identified that many participatory attempts are top-down, more concerned with process than product, and tended to replicate existing patterns of power and privilege. Overall, children remain largely invisible through tokenistic and poorly executed approaches to their participation (Strazdinis and Skeat 2011). Further, it is in professions such as paediatrics and public health (Meucci and Schwab 1997, Sheffield and Landrigan 2011), rather than in education, that calls for children’s agentic participation, especially in light of climate change and other environmental threats, are being made. Early childhood educators, too, need to see active participation as offering agency to young children so that they can make contributions that create better conditions for both present and future childhoods (Daniels-Simmonds 2009, UNICEF 2013).

Dimension 3: recognizing collective rights

According to the UN Regional Information Centre for Western Europe (2012), existing human rights treaties including the UNCRC (1989) are poor vehicles for maintaining and supporting collective rights such as those aimed at creating the conditions necessary for a common sustainable existence, or for recognizing the rights of marginalized groups such as children, women, Indigenous peoples and the poor (Boyd 2010) who should be an integral part of sustainable communities. This is because most treaties reflect an individualistic concept of rights and rights-holders. Collective rights...