This is a test

- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Controversies in Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

After providing a history of the development of the juvenile court, this book explores some of the most important current controversies in juvenile justice. Original essays review major theories of juvenile delinquency, explore psychological and biological factors that may explain delinquent behavior, and examine the nexus between substance abuse and delinquency. A final chapter provides a comparative analysis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Controversies in Juvenile Justice and Delinquency by Peter J. Benekos, Alida V. Merlo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Corrupción política y mala conducta. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Reflections on Youth and Juvenile Justice

Introduction

Since the 1980s, juvenile justice policies have been both punitive and progressive. Most notable among harsh sanctions were changes to state statutes which not only made it easier to try juveniles as adults, but also resulted in more youth being incarcerated in adult institutions. Simultaneously, there are signs of an emergent reaffirmation of the juvenile court’s original mission; specifically, a more rehabilitative and community-based response to youthful offending. For example, California’s SB 81, signed into law in 2007, designates a different direction in the treatment of youth. The legislation precludes counties from committing nonviolent juvenile offenders to the Division of Juvenile Justice, and authorizes block grant funds to local jurisdictions to create alternative treatment options (Commonweal, 2007). Although this is one state’s recent response, it is indicative of a greater emphasis on the community’s role in preventing and rehabilitating youth and a policy that focuses on deinstitutionalization of juveniles.

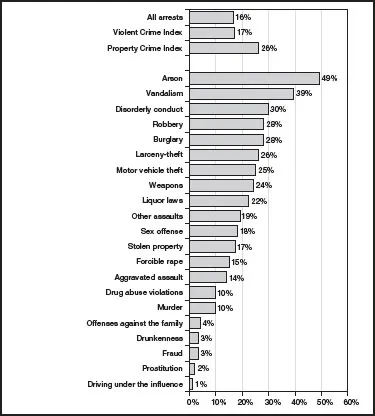

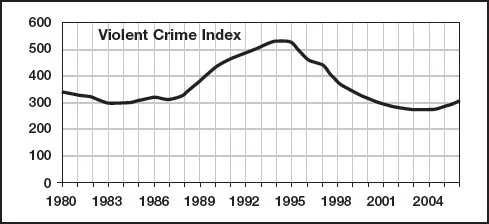

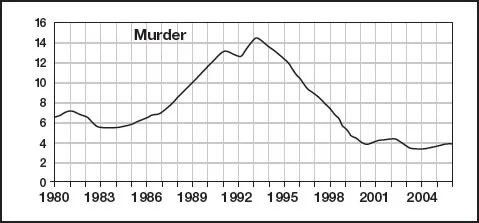

While additional developments in juvenile justice will be reviewed, it is useful to examine trends in juvenile crime as a context for understanding youth policies and legislative reforms. Contrary to general impressions, a snapshot of juvenile arrests in 2006 illustrates that juveniles accounted for 16 percent of all arrests and 17 percent of violent crime arrests (Figure 1.1). In 2004, juveniles accounted for 16 percent of all arrests and 12 percent of all violent crimes cleared by arrest (Snyder, 2006). As demonstrated in Figure 1.2, since 1980, with the exception of the late 1980s until mid 1990s, the rate of juvenile arrests for violent crime has been fairly stable. The impact of this “crime wave” is underscored by the murder rate and the visibility of juveniles in driving up violent crime rates (Figure 1.3). It was during this period of time that much of the get-tough legislation that focused on adultification and punitive sanctions was introduced.

Figure 1.1 Juvenile Proportion of Arrests by offense, 2006

Source: OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book. Online. Available: http://ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/crime/qa05102.asp?qaDate=2006. Released on December 13, 2007.

Figure 1.2 Arrests per 100,000 Juveniles ages 10–17, 1980 – 2006

Source: OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book. Online. Available: http://ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/crime/JAR_Display.asp?ID=qa05201. December 13, 2007.

Figure 1.3 Arrests per 100,000 Juveniles ages 10-17, 1980 – 2006

Source: OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book. Online. Available: http://ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/crime/JAR_Display.asp?ID=qa05202. December 13, 2007.

Arguably, the increase in juvenile violence indicated in Figures 1.2 and 1.3 was attributed to the confluence of gangs, guns, and drugs (Blumstein, 1996).

After a period of a sustained decline in youth crime, the FBI Uniform Crime Report data illustrate that juvenile arrests for murder in 2006 increased about 3 percent from 2005 arrests, with 764 youth under the age of 18 arrested for murder. Arrests of youth under the age of 18 for armed robbery also increased 18.9 percent from 2005 to 2006 (Uniform Crime Reports, 2007). Although the increases are troubling, in their analysis of 2005 data, Butts and Snyder caution us to refrain from drawing conclusions that react to a “relatively small increase” reported in a few major cities (2006:8). In short, it is too soon to conclude that youth are becoming more violent.

These statistics and the analysis of crime trends suggest conflicting images. Increases in juvenile arrests for murder and armed robbery do not fit with perceptions of youth being less violent than in the previous decade. Nonetheless, the incidence of arrests for youth under the age of 18 in 2006 was 1.9 percent more than 2005, but 26 percent less than 1997 (Uniform Crime Reports, 2007). These comparisons suggest that a slight increase in juvenile arrests does not portend a new wave of youth violence.

Understanding Juvenile Justice

Since its founding in 1899, the juvenile court has become increasingly more procedural and formal, and public attitudes toward youthful offenders also have changed. Although the juvenile justice system was originally intended to provide youth with an alternative to adult criminal court (i.e., diversion), there has been a significant transformation in policies toward youth. Specifically, society is inclined toward accountability of youth and more punitive approaches to delinquent behavior.

Even though the juvenile crime wave of the 1980s and 1990s has ended, its continuing impact on juvenile justice policies is evident. Images of young, violent, armed offenders engaged in gang and drug activities undermine the notion of innocent children and developing adolescents, and support arguments against the need for a separate jurisdiction for youth (Merlo & Benekos, 2003). It is difficult for society to reconcile these diverse perceptions of youth.

A review of juvenile justice history suggests at least three salient developments that have had a dynamic impact on the juvenile justice system. Media coverage of youth violence resulted in exaggerated public fear of crime and fostered emotional reactions that bordered on hysteria. Stories of unprecedented youth violence and victimization of innocent citizens contributed to inaccurate perceptions and misunderstanding about juvenile delinquency and the juvenile justice system (Benekos & Merlo, 2006; Merlo & Benekos, 2000a; Kappeler, Blumberg & Potter, 2000).

A second and related emotional response to the fear of youth crime was anger and frustration which promoted a “demonization” of youth (Vogel, 1994). In her review of this phenomenon, Triplett used Tannenbaum’s concept of the “dramatization of evil” to explain how reactions to violent youth were generalized to all youths and, in particular, to inner city minority males (2000:132). As a result, adolescent offenders were portrayed as “super predators” who were dangerous and remorseless (DiIulio, 1995; Bazelon, 2000). In his treatise on youth crime and moral panics, Schissel described the tendency to overstate the youth crime problem (especially gangs) and to “create and foster a collective enmity towards youth” that results in making youth into ‘folk devils’” (1997:51).

These responses of anger and frustration were not only directed toward youth; the juvenile justice system was also criticized for its perceived failure to effectively treat youth and its inability to control youth crime. In their national assessment of juvenile offenders who were housed in adult correctional facilities, Austin, Johnson, and Gregoriou summarized the impact of public attitudes and concluded that “This concept of a distinct justice system for juveniles focused upon treatment has come under attack in recent years” (2000:ix).

These developments – exaggerated media coverage, demonization of youth, and loss of faith in the juvenile justice system – were used by legislators to drive policies that resulted in a shift of discretion from judges to prosecutors, reduced the individualization of sanctions, and further adultified the juvenile justice system. As a result, convergence of the juvenile and criminal justice systems prompted some to contend that the juvenile justice system should be abolished. With a cooptation of the therapeutic goals that guided the founding of the juvenile justice system, deterrence, incapacitation, and punishment became the reality of juvenile justice (Feld, 1993; 1999).

The conservative “get-tough” attitude that characterized criminal justice policy since the late 1970s has been incorporated into policies for youth. By revising juvenile statutes, most legislatures have re-evaluated perceptions of youth and reformulated policies toward youthful offenders. Overall, these policies have tended to treat youth more harshly.

One measure of these changes is the increase in the number of youth in out-of-home placements. According to Snyder and Sickmund (2006:199), the number of youth in public and private facilities increased 41 percent from 1991 to 1999 and then decreased 10 percent between 1999 and 2003. Overall, the increase between 1991 and 2003 was 27 percent. Even though crime rates for adults and juveniles have continued to decline, punitive attitudes persist and fear of crime remains a salient public concern.

Simultaneously, politicians have seized the crime issue and proposed harsher sanctions for juvenile offenders. Candidates for public office understand the importance of shibolleths that emphasize strict sanctions for youth, and they embrace them. The media have also influenced perspectives on youth and helped to solidify the belief that youth are “mini-adults” who should be held to the same standards and subject to the same punishments. For example, findings from a Canadian survey suggest the widespread nature of these changes and the “considerable pressure to impose harsher penalties on juvenile offenders” (Tufts & Roberts, 2002:46). In her study, Sprott found that a majority of respondents opposed a separate system for youthful offenders and perceived that youth in the juvenile justice system received sanctions that were too lenient (Sprott, 1998). While studies such as these also find that the public is not well informed about juvenile justice policy, nonetheless, the “views of the public and the reaction of politicians are clearly linked in a spiral of punitiveness” (Tufts & Roberts, 2002:48). In this prevailing climate of intolerance, zero-tolerance policies have become popular solutions to the complex problems of adolescent behaviors. A survey of college students found that a majority supported zero-tolerance policies and drug testing in high schools (Merlo, Benekos & Cook, 2001).

School policies that mandate expulsions for weapons (i.e., mandatory sentences for youth) have captured media attention, often for their excessiveness in punishing youth for innocent behaviors (e.g., bringing nail clippers to school; sharing mints). Students who have minor violations can be punished as severely as students who bring weapons to school (New York Times, 2002). Incidents such as these prompted one parent to say that “Zero tolerance doesn’t mean zero judgment or rights” (CNN, 2002:par 4). This underscores that reactionary policies that restrict discretion and emphasize punishment may actually distort justice and be an iatrogenesis that does more harm than good (Miller, 1996).

In this introductory chapter on the controversies in juvenile justice, the authors review the evolution of juvenile justice, examine the influence of ideology, politics, and the media on juvenile justice policy, consider recent trends that reaffirm rational policies and therapeutic interventions, provide a context for assessing future initiatives for the juvenile justice system, and offer support for policies that seek to expand innovations that maintain emphasis on prevention, early intervention, and jurisdictional separation.

History and Development of the Juvenile Court

The classic interpretation of the juvenile court is that a special court was established through the efforts of child savers and concerned citizens in order to protect children from the harms of criminal court and to use social welfare programs to save wayward youth (Taylor, Fritsch & Caeti, 2007; Bortner, 1988; Platt, 1977). The parens patriae doctrine that the state would act as a kind and benevolent parent underscored a different philosophy and a therapeutic system to care for the best interests of children. Not surprisingly, “the juvenile court corresponded with the rise of positivism” which Albanese describes as an emphasis on environmental influences as opposed to rational, calculated criminality (1993:9). Ferdinand and McDermott also discussed this presumption of the new court: “Under parens patriae, juveniles, for example, have a right to treatment for their offenses instead of full punishment …” (2002:91).

Concepts such as paternalism, best interests, informality, and treatment characterized this early period. A different perspective, however, of this separate system criticized the increased social control over poor, immigrant children and the justification that it presented for removing children from their homes and families (Albanese, 1993:9). For example, Bernard observed that “like the new idea of juvenile delinquency, the juvenile court was probably popular in part because it sounded new and different but it actually wasn’t” (1992:101). This new legal philosophy justified institutionalization to control children for their “own good” but at the same time helped to “increase the power of the state” over poor urban youth (Bernard, 1992:106).

Eventually, abuses of this new court’s informal authority reached the attention of the Supreme Court and its resulting decisions began to transform the juvenile court. In his assessment of the state of juvenile justice, Feld examined the outcomes of the Court’s decisions: the juvenile court relied less on informal procedures; the philosophy shifted from therapeutic to crime control; and the separate jurisdiction for children and youth was eroded by the diversion of status offenders and the transfer of serious adolescent offenders to criminal court (1993; 1999). Essentially, this created a convergence of procedure, jurisprudence, and jurisdiction, and prompted Feld to ask: What was the justification for separate but parallel systems of justice? His critique of the resulting transformation suggested that youth received neither due process protections nor treatment, and as a result, Feld proposed the abolition of the juvenile court (1993; 1999).

Butler County, Pennsylvania Juvenile Court: Adjudication Hearing

While the mission of the juvenile court may have reflected an admirable objective, the reality of how youth were treated was condemned. In the context of hardening attitudes toward youth and with a system depicted by deficit performance, juvenile justice at the beginning of the twenty-first century was bleak.

Ideology, Politics, the Media, and Juvenile Justice

The developments and transformation of the juvenile justice system summarized above did not occur unilaterally. A gen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Reflections on Youth and Juvenile Justice

- Chapter 2 What Causes Delinquency? Classical and Sociological Theories of Crime

- Chapter 3 Delinquency Theory: Examining Delinquency and Aggression through a Biopsychosocial Approach

- Chapter 4 Youth, Drugs, and Delinquency

- Chapter 5 Violence and Schools: The Problem, Prevention, and Policies

- Chapter 6 A World of Risk: Victimized Children in the Juvenile Justice System – An Ecological Explanation, a Holistic Solution

- Chapter 7 Prosecuting Juvenile Offenders in Criminal Court

- Chapter 8 Youth Behind Bars: Doing Justice or Doing Harm?

- Chapter 9 Race, Delinquency, and Discrimination: Minorities in the Juvenile Justice System

- Chapter 10 In Trouble and Ignored: Female Delinquents in America

- Chapter 11 Sentenced to Die: Controversy and Change in the Ultimate Sanction for Juvenile Offenders

- Chapter 12 Comparative Juvenile Justice Policy: Lessons from Other Countries

- Contributors’ Biographical Information

- Index