This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The City in Biblical Perspective

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The city is an ambiguous symbol in the Bible. The founder of the first city is the murderer, Cain. The city of Jerusalem is the place chosen by God, yet is also a place of wrong-doing and injustice. Jesus seems to have largely avoided cities except Jerusalem, where he was crucified. 'The City in Biblical Perspective' examines the archaeological and social background of the urban biblical world and explores the implications of the deliberate ambiguities in the biblical text. The book aims to deepen our understanding of both the biblical and the contemporary city by asking how the Bible's complex understanding of the city can illuminate our own ever more urban time.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The City in Biblical Perspective by J.W. Rogerson, John Vincent in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

THE CITY IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

J. W. Rogerson

INTRODUCTION

The word “city” is not easy to define. There is no equivalent in French or German, where the words “ville” or “Stadt” can be translated as either city or town. A popular misconception in Britain is that a city is a place with a cathedral. This is disproved by the fact that Southwell and Southwark have cathedrals but are not cities, and that Cambridge and Cardiff are cities but do not have cathedrals. These examples could be multiplied. Strictly speaking, a city in Britain is a settlement that has been given a charter entitling it to call itself a city. This often has its roots in past history so that some cities are comparatively small and unimportant politically or economically (such as Durham), while others are the opposite (such as Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool).

The same problem of definition is to be found in the Old Testament. Students who are beginning Hebrew are usually taught that ‘îr means city, ignoring the fact that “city” in English is difficult to define! In fact, the Hebrew word ‘îr can be used in many different ways. It can be used without qualification, for example, of Jericho in Joshua 6:3, where English translations render the word as “city”. It can also be used, with an appropriate adjective, to describe unwalled villages, as in Deuteronomy 3:4 or fortified cities, as in 2 Kings 17:9.

The strict answer to the question “What is a city?” is that it is a word that can be used in a number of different ways to refer to human settlements that may vary considerably among themselves. However, this is not a complete, or even satisfactory, answer. The word “city” has acquired a good deal of emotional and other baggage. For some users of English, the word will suggest crime, traffic congestion, deprived areas and ethnic tensions. Others may think of theatres, prestigious shops and stores, specialist retail quarters and famous restaurants. While this may seem to open up a gap between the experience of life in biblical and in modern times, this may be more apparent than real. The question, why what the Bible contains about cities (however understood) should be of any interest to modern readers or citizens, is a very proper one. It can begin to be answered in the following way.

When modern users of English associate the word “city” with the factors mentioned above, they are pointing to the fact that cities (or large towns; but I shall continue to use the word “city”) are places where power and resources are concentrated. The industrial revolution in Britain saw the creation of cities as centres of manufacturing and trade. Textiles, iron and steel, ship building, trading in things such as tea and sugar, led to the creation of modern industrial cities, leading to enormous increases in wealth and population as well as poverty and crime. Even though Britain is now a largely de-industrialized country, its former industrial cities remain centres of wealth, power and resources together with the many social and other problems that such concentration brings with it.

Again, at first sight this seems so different from the situation in biblical times that the question has to be asked how the Bible can have any bearing upon the city in the modern world. Most people in ancient Israel did not live in cities and, as will be described later, some of the Israelite cities, in any case, had little space for people actually to live in. But, like modern cities, Israelite cities were places where power and resources were concentrated. They were the centres where justice was administered, trade carried on, records kept, scribes trained, armies recruited, labour organized, power exercised. Although they did not touch the lives of ordinary people in the way that modern cities affect today’s world (it is estimated that by 2025 60 per cent of the world’s inhabitants will be urban dwellers; see Giddens, 1992: 292–301) they attracted the attention of Old Testament prophets and writers in a significant way. As centres of power and administration they determined the character of the nation they represented. The values and ideals of those in power in the cities often came in to conflict with prophetic and prophetically-inspired hopes for a nation supposedly loyal to a God of justice. The city, as referred to in the Old Testament, thus became a powerful and necessarily ambiguous symbol. As an institution that summed up human nature in all its selfishness and destructive inhumanity, it was described as having been founded by Cain, who murdered his brother Abel (Gen. 4:17). As an institution which, justly and rightly governed in obedience to God, could be a blessing to humanity, it became a symbol of hope for the nations of the world (Isa. 2:2–4/Mic. 4:1–4). In what follows, there will be two main sections. The first, based upon archaeology, will describe Israelite cities: their size, nature and functions. The second section will be based upon Old Testament texts that deal in different ways with the theme or ideas of the city. A closing section will draw conclusions.

Chapter 1

THE ISRAELITE CITY: HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY

The Israelites did not invent cities and city life; they took over institutions that had existed for at least two thousand years before the heyday of Israelite cities (c. 925–720 BCE). The distinctively Israelite contribution was the prophetically-derived critique of cities and city life based upon belief in a God of justice. Urbanization in ancient Palestine began around 3000 BCE, with settlements such as Jericho and Megiddo which were characterized by large public buildings, including temples (see generally Fritz, 1990: 15–38). The urbanization process reached its peak around 2650–2350, and then underwent a decline, with many cities disappearing by around 2000. The causes are unknown. They could have included a decrease in rainfall, and a lowering of water tables, and inter-city rivalry and warfare. A second phase of urban expansion and subsequent decline took place in the period 1800–1200 BCE.

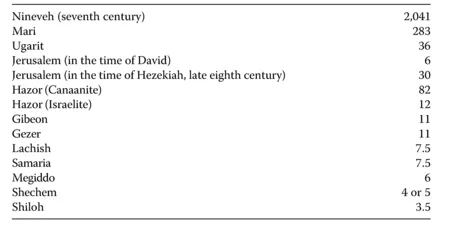

Israelite cities took over and rebuilt existing cities. This is true, apparently, even of Samaria, where the Bible gives the impression that it was a completely new foundation built on the initiative of the Israelite king Omri (see 1 Kgs 16:24; de Geus, 2003: 43). The striking thing about the Israelite cities is how much smaller they were than the most important centres of population in the ancient Near East. Also, some Israelite cities, such as Hazor, occupied only a small part of the site that had made up the preceding Canaanite city. Tables 1.1 and 1.2 give some idea of the size of Israelite cities compared with other settlements. Although the figures are estimates and in some cases (e.g. that of Jerusalem) controversial, they give a general indication of the state of affairs. The figures are hectares (a hectare being 2.47 acres).

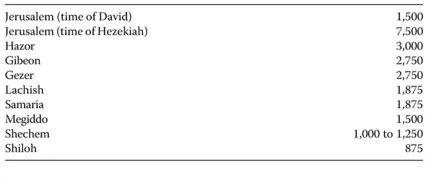

The small size of Israelite cities raises the question of the number of their inhabitants. This is a matter fraught with complications. It has been argued that cities such as Megiddo, Samaria and Hazor during the period 925–720 had some 80 per cent of their space occupied by public buildings, the remaining space being open to accommodate fairs, pilgrims, armies and residents from surrounding areas in time of danger. At the same time, administrative centres such as Megiddo, Samaria and Hazor could hardly have functioned without an adequate number of personnel. These people probably lived outside the cities, either in the immediate vicinity in quarters whose remains have not been preserved, or in nearby villages whose buildings have suffered a similar fate (see de Geus, 2003: 179–80). Broshi and Gophna (1986) have suggested an average density of around 250 inhabitants per hectare in the pre-modern Near East. Bearing in mind the difficulties outlined above, this would give the following rough populations for Israelite cities:

Table 1.1

These figures may have no value at all. On the other hand they may serve to alert us to the fact that when we think about Israelite cities we must think in terms of small units that do not resemble anything comparable to modern urban experience.

Table 1.2

De Geus has suggested that an Iron Age city in Palestine may have resembled a mediaeval European city in some respects. Similarities would include the city walls, with the highest part of the complex dominated by a castle and perhaps a cathedral in a mediaeval city, and by a fortress and palace or residence in the Iron Age case. The height of the wall and of the most important buildings would be intended to impress the local population and to deter potential enemies (de Geus, 2003: 167–68). Differences would include the fact that in Iron Age cities trade, justice and perhaps religious ceremonies (de Geus, 2003: 37–39) were carried on at the city gate and spaces immediately adjacent to it, while there would have been a special building for these activities in the mediaeval counterpart. The comparison between the Iron Age and mediaeval city enables the main functions and characteristics of the Israelite city to be listed (for what follows see de Geus, 2003: 171).

- It housed or made possible the work of specialists, such as administrators, scribes or religious functionaries, all of whom were not primarily engaged in the production of food.

- It contained public buildings used for collecting and distributing resources such as taxes.

- It was a centre for trade and for the location of specialist services such as those provided by potters, smiths, metal workers and scribes.

- It was a centre for the administration of justice.

- Although probably governed by the heads of powerful families, it was a society constituted by allegiance to the city and its functions, rather than one based entirely upon kinship, and it exhibited distinctions based upon class (i.e. wealth).

The next chapter will deal with biblical texts that treat the theme of the city theologically. For the moment, some biblical passages will be examined which can be better understood in the light of modern knowledge of Iron Age cities.

The story of Noah in Genesis 6–9 is not obviously concerned with a city, and is not even located anywhere. It is also based upon, or shares traditions common with, other flood stories known from the ancient Near East (see Rogerson and Davies, 2005: 120–22). However, hearers or readers of the biblical story would arguably have connected it with a city because of the special skills implied in the construction of the ark. It is unlikely that one man would have combined the skills of carpenter, ship designer, and expert in the application of pitch, to mention only those detailed in the narrative. The acquisition of the wood and the pitch, necessary for the ark’s construction, not to mention the purchase of the food for the ark’s crew and animals, would have required the combination of trading and the transporting of materials that only a city could have organized. Of course, the story is not historical; but for hearers and readers it implied a level of human organization and co-operation that was arguably more apparent to people in the ancient world than to modern westerners, who take it for granted that the materials they may require for DIY work in the home will be readily available in a large warehouse-type store.

The story of Sodom in Genesis 19 describes Lot as sitting in the city’s gate. Because Lot greets the two angelic visitors when they reach the city it might be concluded that he was sitting alone at the gate. This would be a mistake. The gate of a city was a complex of fortified buildings designed to give maximum protection in times of danger and easiest access on other occasions. A space, or square, either between two gate complexes or on the inside of them, was the principle area in a city where justice was administered (see Ruth 4:1–2) and trade carried on. It is most unlikely that Lot would be sitting alone in the square at the gate. Again, the story is not historical but the conventions shared by the author and hearers/readers would assume that Lot was sitting with other men, who would observe the arrival of the unusual visitors. The visitors initially decline Lot’s invitation to his home and say that they will spend the night “in the street” (RSV). Later versions, such as the NRSV, have, rightly, “in the square” . The visitors were not planning to sleep rough. It would not be unusual for visitors to spend the night in the square. The gates would be closed for protection against marauders and wild animals, and there were no inns or hostelries. Perhaps the story implies that it was the fact that Lot took the men into his house that aroused the curiosity of the inhabitants of the city. The narrative also plays upon the fact that Lot’s position in the city is that of a sojourner (Gen. 19:9) rather than an established citizen. That, in these circumstances, he possessed a house in the city may have been a function of his wealth. Although the details discussed here are not central to the narrative, they are not without interest, and warn modern readers against reading their own city-dwelling experiences into the narrative.

In the Jubilee law of Leviticus 25:29–31 a distinction is made between a house in a walled city and one in a village with no wall. The former type of house, if sold, may be bought back by the vendor but only within one year of purchase. Thereafter it is the possession of the purchaser in perpetuity (unless, of course, the purchaser sells it after an interval of time) and it is not subject to the Jubilee law. The house in the unwalled village is subject to the Jubilee law, which means that it may be bought back at any time and, in any case, will revert to the original owner at the forty-ninth or fiftieth year. Part of the theological justification of the Jubilee is that the land belongs to God and that the use of it should reflect God’s compassion. The economic forces that drive people into debt and slavery must not be allowed to establish permanent human conditions. Therefore, there should be periodic adjustments in order to restore dignity and independence to those who have fallen upon hard times. This is achieved, among other measures, by the restoration of lands to their original owners, lands that had been sold to meet debts.

Given this view, it is natural to ask why houses in walled cities should be treated differently from those in unwalled villages, and be exempted from the Jubilee laws. According to Noth (1965: 190) the distinction rested upon the persistence of ‘ancient city law’ that went back to ‘Canaanite’ times. Although Noth gives no evidence for this it has a certain plausibility. Given that Israelite cities were rarely, if ever, new foundations, certain rights and privileges may have been taken over from the pre-Israelite times. The question “who owns the city?” may have been impossible to answer; and it may have been that walled cities were believed to possess legal privileges (see de Geus, 2003: 23).

But there may also have been a simple, practical reason for the exemption. Israelite towns were very small in area, and although there may have been some free-standing houses of the four-roomed type, most houses were probably one-roomed dwellings with shared external walls. In some cases they were part of the casemate wall that surrounded the city. They were liable to damage and d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Part 1 The city in the Old Testament

- Part 2 The city in the New Testament

- Epilogue Making Connections

- Bibliography

- Index of Biblical References

- Author Index

- Subject Index