eBook - ePub

Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Adolescents

Settings, Treatments, and Diagnoses

This is a test

- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Adolescents

Settings, Treatments, and Diagnoses

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Adolescents is an essential, user-friendly guide for clinicians who wish to implement DBT for adolescents into their practices. The authors draw on current literature on DBT adaptation to provide detailed descriptions and sample group-therapy formats for a variety of circumstances. Each chapter includes material to help clinicians adapt DBT for specific clinical situations (including outpatient, inpatient, partial hospitalization, school, and juvenile-detention settings) and diagnoses (such as substance use, eating disorders, and behavioral disorders). The book'sfinal sectioncontains additional resources and handouts to allow clinicians to customize their treatment strategies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Adolescents by K. Michelle Hunnicutt Hollenbaugh, Michael S. Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction and Overview

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is considered a ‘third wave’ Cognitive Behavioral Therapy—which means it’s a type of CBT that also includes other interventions and approaches (for example, dialectics and mindfulness). Marsha Linehan began developing this treatment several decades ago, and since then it has saved communities thousands of dollars by helping clients avoid inpatient hospitalizations and acute mental health care (Linehan, 2015). This is accomplished by working with clients so they are reinforced for using new skills to cope with and manage emotions, instead of resorting to life-threatening behaviors such as self-injurious or impulsive behaviors. Originally, Linehan developed DBT for individuals (primarily women) diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD). However, since then, research on DBT has expanded substantially. Researchers have used DBT in many different settings for both adults and adolescents struggling with a variety of diagnoses (Fleischhaker et al., 2011). This research includes but is not limited to: eating disorders (Salbach-Andrae, Bohnekamp, Pfeiffer, Lehmkuhl, & Miller, 2008), bipolar disorder (Goldstein, Axelson, Birmaher, & Brent, 2007), inpatient treatment (Katz, Cox, Gunasekara, & Miller, 2004), residential settings (The Grove Street Adolescent Residence, 2004), and schools (Ricard, Lerma, & Heard, 2013).

Currently, there aren’t many evidence-based treatments available that focus specifically on treating adolescents struggling with pervasive emotion dysregulation (the inability to effectively manage emotions in most life situations). There are also a lot of adolescents who do not respond well to traditional treatment methods—or they may simply benefit from supplemental interventions in addition to the treatment they are currently receiving. For these reasons, DBT is a great option for clinicians who are working with adolescents.

Why DBT Is Different

When Linehan originally started working with clients with borderline personality disorder, she noticed the type of intervention she was using was not always effective. When she used a behavioral, problem-solving approach, she found it was too focused on change, and clients became resistant. When she used a more person-centered approach, she found the focus was too much on validation, and clients were unable to problem solve in order to make necessary changes. As a result, she developed DBT as a new type of approach that provides flexibility to use both validation and change in the context of the client’s current situation (Linehan & Wilks, 2015). DBT also addresses several problem behaviors at the same time. Treatment targets (goals) are addressed through several modes (types of treatment): including skills groups, individual sessions, and family sessions. This increases the intensity of treatment, but it also increases the adolescent’s success in learning and using skills while decreasing problem behaviors.

How to Use This Book

Our goal in writing this book is to share approachable material for you to use in your practice. Hopefully you will find this information useful on its own; however we also recommend reading the foundational texts by Linehan (1993’s Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder) and Miller, Rathus, and Linehan (2007’s Dialectical Behavior Therapy With Suicidal Adolescents). Though we will give basic explanations of the foundational principles of DBT here, those texts go much more in depth and will help you understand the material.

We organized this book for maximum utility. This introduction will give an overview of DBT, including all of the basic principles, functions, and modes of treatment. Chapter 2 will include specifics on implementing DBT in your setting, decisions to consider when adapting DBT, and the importance of commitment strategies. Additionally, it will explore multicultural considerations. Chapter 3 will discuss how to develop a consultation team and describe DBT as a collaborative approach to treatment. Then, Chapters 4 through 8 will discuss considerations for implementation in specific settings (different levels of care, schools, and forensic settings). Chapters 9 through 13 will discuss specific diagnoses, and adaptations for adolescents struggling with eating disorders, conduct disorders, substance use disorders, other diagnoses, and how to address comorbidity and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) specifically. Finally, Chapter 14 will include a summary and conclusions. The text will include usable handouts based in DBT for each corresponding chapter.

Terminology

Counselors, social workers, psychologists, and other professionals alike will find this text helpful, but for the sake of brevity we will use the term clinician to refer to any professional working in these capacities. We will also use the term client when discussing the adolescents you will be treating, though we are aware that you may refer to them as patients, students, etc. There are a lot of different terms used in DBT that will be described in this chapter and the next chapter—refer to Table 1.1 for a basic definition of all of these terms.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Treatment Mode | A treatment mode describes how DBT will be provided. This includes skills groups, individual counseling, phone coaching, and consultation team. You can decide which modes to implement based on the needs of your settings and your clients. |

| Skills Module | In DBT skills training with adolescents, there are five psychoeducational skills modules: mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and walking the middle path. These modules are usually taught via psychoeducational skills groups. |

| Treatment Strategies | There are several types of treatment strategies in DBT. The strategies discussed in this book include dialectical, core (validation and problem-solving), stylistic, case management, and commitment. We believe these will be the most applicable to readers; however there are more strategies discussed in depth in Linehan’s (1993) original text. |

| Stages of Treatment | There are four stages in DBT treatment. Stage one has received the most attention, and is the most common, as this is when skills groups take place. |

| Treatment Targets | There are several hierarchical treatment targets that are identified for each individual client. These include decreasing life-threatening behaviors, decreasing therapy-interfering behaviors, decreasing quality-of-life-interfering behaviors, and increasing behavioral skills. These are addressed via the modes of treatment and facilitated by the strategies employed by the clinician. |

| Treatment Functions | Miller et al. (2007) stated that treatment targets cannot be addressed unless the program as a whole addresses the following treatment functions: improving motivation to change, enhancing capabilities, ensuring skill generalization, structuring the environment to support clients and clinicians, and improving therapist motivations. |

The Biosocial Theory of Emotion Dysregulation

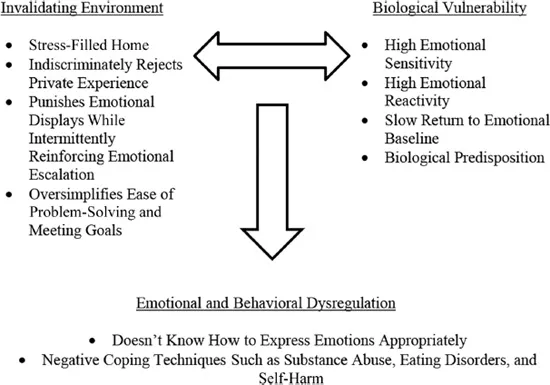

Dialectical Behavior Therapy is based on the biosocial theory of emotion dysregulation. Emotion dysregulation is “the inability, despite one’s best efforts, to change or regulate emotional cues, experiences, actions, verbal responses, and/or nonverbal expressions under normative conditions” (Koerner, 2012, p. 4). Basically, the biosocial theory states that pervasive emotion dysregulation is the result of two interacting phenomena—biological predisposition to emotional vulnerability and an invalidating environment (see Figure 1.1). Biological predisposition means the adolescent’s brain is biologically different, and therefore he or she is more vulnerable to volatile emotions than others. These adolescents may experience emotions more frequently and intensely, and they may have more difficulty managing those emotions. The invalidating environment is often experienced as emotional neglect or harm from parents or other significant adults, siblings, and peers. They learn that their emotions are not important, wrong, or they are simply ignored. As a result, these adolescents do not learn effective methods of regulating emotions, and then they experience pervasive emotion dysregulation. The interaction of these two variables can lead to behaviors with potential harmful consequences—including self-injury and suicide attempts (Linehan, 1993). See Handout 1.1 for a handout that explains the biosocial theory to adolescents and parents. Without intervention, pervasive emotion dysregulation can develop into more severe disorders. By using DBT, clinicians (and parents) can stop reinforcing the harmful, life-threatening behaviors that the adolescent is currently using to manage his or her emotions, and instead teach him or her new and effective ways to cope.

Figure 1.1 Biosocial Theory

Dialectics

The term dialectic may be new to some readers. It means the synthesis of opposites—that two, seemingly opposite, ideas or phenomena can both be correct and co-exist (Linehan, 1993, p. 30). DBT treatment is, in itself, dialectical as clinicians work with clients to validate them in their current situation, while also helping them make changes for the better. One of the most important underlying assumptions in DBT is that the client is doing the best that he or she can, and he or she can also do better (Linehan, 1993). This highlights the dialectical nature of DBT—two ideas that appear to be contradictory are both correct. Clinicians can take a dialectical approach to counseling by being flexible and viewing reality as something that is always changing, and that all aspects of reality are interrelated. In session, clinicians are encouraged to find balance (Linehan referred to this balance as being on a “teeter-totter” with the client on one side, and the clinician on the other, 1993, p. 30) and to ask “what are we leaving out?” When teaching dialectics to clients, it is important to emphasize the use of the terms “both” or “and” as opposed to “either” and “or.” In fact, one of the key concepts of DBT, the Wise Mind, is the dialectic between the emotional and the reasonable minds (Linehan, 2015).

Initially, I (the first author of this book) found the concept of dialectics to be vague and ill defined at times—but after spending time with it I think that ambiguity is in itself a description of being dialectical. Nothing is set in stone; nothing is black or white. Everyone perceives reality through his or her own lens and that is what makes two sides of a situation equally correct. For individuals, it is correct for them to see the situation in their own manner, based on their own experiences.

Modes of Treatment

By now, you have probably discovered how complex DBT treatment is. In traditional DBT, there are several modes of treatment—that is, different facets that make up the complete course of treatment. Fortunately, there is a lot of research that shows that not all modes of DBT treatment are necessary for positive treatment outcomes. Instead, clinicians should focus on what will work best given the setting they work in and the clients they are treating. However, if the program does not offer all of the standard DBT modes, it does not meet the requirements to be considered full DBT. Clinicians should disclose this readily to clients—Linehan and colleagues suggest terming the program as DBT informed instead. The standard DBT modes include psychoeducational skills groups, individual sessions, intersession phone coaching, and a clinician consultation team (Linehan, 2015).

Skills Groups

Psychoeducational skills groups are adapted to fit the needs of the setting and can be altered for the needs of the adolescents. Traditionally, they last for two hours weekly. The first hour consists of reviewing homework and diary cards and the second hour consists of learning new materials. Mindfulness practice is conducted at the beginning and the end of each session, to emphasize the importance of this skill, and increase the adolescents’ ability to use this skill. Typically, groups are closed during each module and then opened again at the beginning of a new one. This provides the group a sense of cohesion and comfort necessary to build skills, and then adolescents who have experience with the material can support and give tips to new members (Rathus & Miller, 2015).

Each module includes homework sheets for each skill learned, in addition to keeping track of the skills the adolescent used throughout the week on his or her diary card. Diary cards are (like they sound) a journal that the client keeps and they can be customized to fit the needs of your client. We have included several versions that are different based on the setting and the diagnosis. They can include moods on any given day, any skills they have previously learned, and any target behaviors the adolescent is working to increase or decrease (Miller et al., 2007). See Handouts 1.2–1.5 for several diary card examples.

Parents and caregivers may also take part in skills groups training, as this helps increase skills acquisition in different settings. Increasing the skills of the parents also serves to decrease any invalidation the adolescent may be experiencing (Rathus & Miller, 2015). Clinicians can initiate skills groups in many different ways, depending on the setting in which they are working. We will discuss different options for implementation further in each specific chapter. A short description of each skills training module, including the adolescent specific module, Walking the Middle Path, is below.

Mindfulness

The practice of mindfulness is considered a foundation of DBT—it is the first skill taught, and is practiced in every session (often several times). Mindfulness is based in Eastern traditions; however, mindfulness from a DBT perspective is not considered meditation. Instead, it is considered a skill to increase awareness in the moment and the ability to manage one’s emotions and thoughts. The premise of mindfulness for adolescents is that they often struggle with racing thoughts, or have difficulty focusing on one thing at a time. By being mindful, they become better at controlling their thoughts instead of letting them be controlled by them (Linehan, 1993). A...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Contributors

- 1 Introduction and Overview

- 2 Treatment Delivery and Implementation

- 3 Treatment Team and Continuity of Care

- 4 Outpatient Settings

- 5 Family Counseling

- 6 Partial Hospital Programs and Settings

- 7 DBT in Inpatient Settings

- 8 Working Within School Sites

- 9 Eating Disorders

- 10 Conduct Disorder, Probation, and Juvenile Detention Settings

- 11 Substance Use Disorders

- 12 Other Diagnoses for Consideration

- 13 Comorbid Diagnoses and Life-Threatening Behaviors

- 14 Summary and Conclusions

- Handouts

- Index