![]()

1

American Poverty

Poverty may well be America’s most serious and costly social problem. Each year millions of Americans live in poverty, and hundreds of billions of public and private dollars are spent on efforts to prevent poverty and assist the poor. Poverty is a complex socioeconomic problem that is causally interwoven with other costly societal ills such as unemployment, underemployment, crime, out-of-wedlock births, low educational achievement, mental, emotional, and physical illness, domestic violence, and alcohol and substance abuse. The cause-and-effect relationship between these problems is complex and greatly debated. Cumulatively these problems account for a huge percentage of all government and charitable spending. They are, in short, a major reason for the size and cost of government.

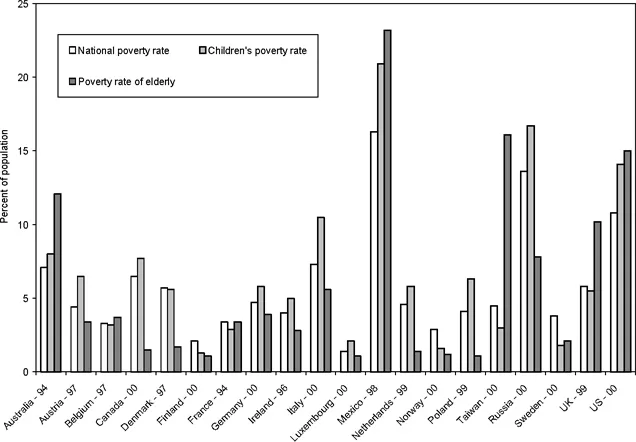

Poverty, of course, is not a new or uniquely American problem. By the standards of modern societies, most of the people who have ever lived on this planet lived and died in poverty. Even today, poverty is a serious problem in every nation, including the most advanced and prosperous societies (Smeeding, 2004). As Figure 1.1 shows, the most modern and advanced nations struggle with poverty, which often involves large numbers of poor.

In less economically developed nations, poverty rates are staggering. Modestly estimated, at least 20 percent of the world’s population lives in stark poverty, barely able to avoid starvation (World Bank, 2004, 7). Many nations do not even pretend to the goal of creating a broad middle-income population; and among those nations that do, creating and sharing wealth in some equitable and effective fashion that produces and nurtures a healthy and extensive middle-income population has always been a challenge imperfectly achieved.

Figure 1.1 Poverty in Selected Nations

Note: Poverty is defined as 40 percent of median income for family size.

Source: Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), Key Figures, available at www.lisproject.org/keyfigures.htm.

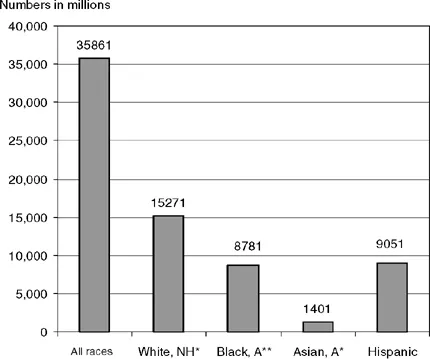

Despite massive outlays and a network of major antipoverty programs, the number of poor Americans is enormous. Every year since the mid-1960s the federal government has tried to identify those Americans living in poverty. In 2003 the federal government estimated that almost 36 million Americans were poor, over 12 percent of the population (Figures 1.2 and 1.3). To put this number in perspective, the collective poverty population in 2003 was almost as large as the total population of California, twice the size of the population of Florida, and several million larger than the entire population of Canada.

The cost of services to the poor is sobering. In 2003 the major welfare programs (for example, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income) involved outlays at the state and federal levels that substantially exceeded $500 billion (see Figure 7.2; Howard, 2003). Poverty, of course, is expensive in more ways than outlays. People idled by poverty lessen the overall productivity of the workforce, lower tax revenues, reduce the nation’s capacity to compete in the global economy, and may reject mainstream values leading to engagement in crime, domestic violence, child abandonment, and other antisocial behaviors that burden society. Poverty, in all its manifestations, is extremely expensive and a drain on the vitality of the nation.

Figure 1.2 U.S. Poverty Count by Race, 2003

Notes: * Non-Hispanic; ** Alone, not in combination with any other race.

Source: (Bureau of the Census (2004a), table 4.

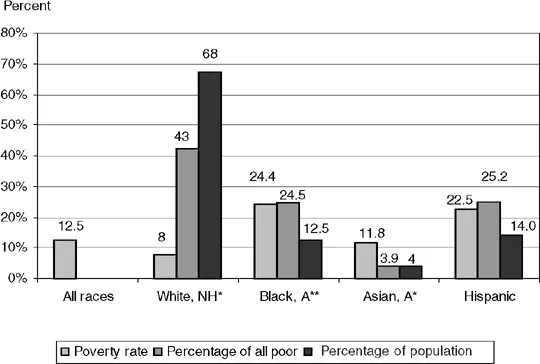

Figure 1.3 Percentage of Population in Poverty

Notes: * Non-Hispanic; ** Alone, not in combination with any other race.

Source: (Bureau of the Census (2004a), table 4.

Poverty also weighs on the national conscience because the poor are the most vulnerable members of the American population—children, single-parent households (mostly headed by women), the poorly educated, the aged, and the handicapped. As Figure 1.2 shows, black and Hispanic Americans suffer particularly high rates of poverty, and children are particularly vulnerable, regardless of race or ethnicity. From 1990 through 2003, the annual number of poor children was 13.7 million. In 2003 over one-sixth of all American children lived in poverty, comprising 36 percent of the total poverty population.

Given the size, cost, and impact of poverty, America has a major stake in preventing this condition and in helping as many of the poor as possible to become self-reliant, economically secure, productive citizens. America’s commitment to dealing with poverty in any major way goes back to the New Deal legislation of the 1930s (Patterson, 1986; Abramovitz, 1988; Allard, 2004). These early, rather modest programs have evolved and matured substantially over time. As welfare expenditures have escalated, especially in the last two decades, skepticism about the cost and effectiveness of these programs has become increasingly widespread both within the government and among the public.

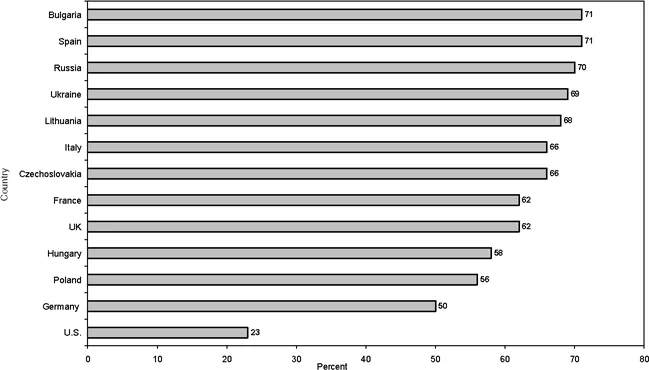

Americans are conservative about the role of government, and highly skeptical of helping the poor in ways that might undermine their sense of responsibility and self-respect. Figure 1.4 shows the results of a recent survey in the United States and twelve other nations. Respondents were asked if they “completely agreed” that it is the responsibility of the government to take care of very poor people who cannot take care of themselves. Notice that only 23 percent of American respondents “completely agreed,” by far the lowest rate among the thirteen nations. In seven of the nations more than 60 percent of the respondents were positive, and in three nations the positive rate was 70 or 71 percent. In this same survey, Americans were much less likely than Europeans to believe that government “should provide everyone with a guaranteed income, reduce the differences in income between people with high and low incomes, and provide a decent standard of living for the unemployed.” Even less-affluent Americans shared these views (ISSP, 2001). Americans, in short, are much less trustful of government than citizens in many other democracies and very concerned about eroding core values and creating a dependent class.

Figure 1.4 Public Obligations to the Poor, 2000

Source: ISSP (2001).

Note: Percent who “completely agreed” that it is the responsibility of the government to take care of very poor people who cannot take care of themselves.

One reason for this conservatism is that Americans believe there is unlimited opportunity for those who work hard. When respondents in Europe and America are asked if they agree that “the way things are in their country, they and their family have a good chance of improving their standard of living,” Americans are the most optimistic. Over 70 percent of Americans agree, compared to only 40 percent of Germans, 37 percent of the British, and 26 of the Dutch. Minorities are almost as optimistic about opportunity in America as whites (ISSP, 2001). Americans believe that this is a land of great opportunity, and that “failure” cannot be rewarded without doing great harm to the most fundamental societal values.

While Americans are conservative and skeptical about welfare, they are often confused about how aid programs are designed and how public dollars are spent (Berinsky, 2002). Welfare is generally thought of in terms of cash aid, but most welfare programs provide services rather than cash. The vast majority of welfare program spending, in fact, is for services. Medicaid, food stamps, child care, housing assistance, Head Start, school lunch programs, and job training programs make up the major costs of welfare. Only about 15 percent of all the poor receive any cash aid (see Figure 7.2), and payments to individuals are rather modest. By far the most expensive programs are those that provide health care to poor and low-income citizens. Primarily because of increases in health care costs, payments for welfare programs increased by 523 percent between 1968 and 2002 (inflation adjusted). During this same period, the American population grew by only 43 percent (see Tables 7.1 and 7.2).

As expensive as America’s major welfare programs are, they are not designed to erase or even greatly lessen poverty. They have always been designed to help families in economic distress for short periods while they get back on their feet. America’s original cash welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), was designed to provide “temporary” aid to select families (mostly female-headed) while encouraging them to leave welfare as soon as possible. AFDC, however, did not effectively require or help the poor leave welfare for the job market. If the head of a poor family entered the job market, most states provided little support or cash. In the mid-1990s, only about half the states provided any cash relief or other help to AFDC recipients working half time. Fewer than a dozen provided any cash support to full-time workers, regardless of how low their income or the size of the family. The result was that even among those families who could qualify for cash assistance, almost all were unemployed and almost all continued to live in poverty. Only rarely did America’s complicated and increasingly expensive programs help the poor escape poverty and become self-reliant and economically secure. Thus, as the overall costs of welfare soared during the 1980s and much of the 1990s, the poverty rate actually increased (see Figure 3.1).

As skepticism about the design, expense, and effectiveness of American welfare programs increased, presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter recommended major welfare reforms to Congress. None was passed. President Reagan also recommended reforms, and an important but poorly funded reform plan reflecting some of his proposals was passed in 1988. Fundamental reform was not adopted until President Clinton’s first term in office. In 1996 a bipartisan coalition in Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). After having vetoed the first two versions of this bill, President Clinton signed the reform plan into law in August 1996.

The new legislation, PRWORA, clearly mirrors America’s conservative values. PRWORA is not a mere incremental adjustment in welfare policy. It is the most comprehensive reform of a major public policy in recent American history. PRWORA aligns welfare with American philosophy much better than was the case with AFDC. The focus of welfare policy under PRWORA has shifted from providing limited and modest cash aid to programs designed to help recipients or potential recipients become viable members of the workforce. The administration of the new reform approach has been turned over to the states, and they are given considerable discretion in designing and implementing policies to help their poor become employed. To make the transition to employment feasible, the states are given grant dollars to help them provide recipients with such critical support services as transitional child care, health care, transportation aid, and even job preparation loans, education, and training. PRWORA also provides states with funds that can be used to significantly improve the quality of child care, after-school programs, and other supervised activities for millions of children from poor and low-income families.

PRWORA is also designed to reduce future generations of poor by funding programs to lower out-of-wedlock births, particularly among teens. It requires both parents to acce...