This is a test

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This new edition of Physical Theatres: A Critical Introduction continues to provide an unparalleled overview of non-text-based theatre, from experimental dance to traditional mime. It synthesizes the history, theory and practice of physical theatres for students and performers in what is both a core area of study and a dynamic and innovative aspect of theatrical practice.

This comprehensive book:

-

- traces the roots of physical performance in classical and popular theatrical traditions

-

- looks at the Dance Theatre of DV8, Pina Bausch, Liz Aggiss and Jérôme Bel

-

- examines the contemporary practice of companies such as Théatre du Soleil, Complicite and Goat Island

-

- focuses on principles and practices in actor training, with reference to figures such as Jacques Lecoq, Lev Dodin, Philippe Gaulier, Monika Pagneux, Etienne Decroux, Anne Bogart and Joan Littlewood.

Extensive cross references ensure that Physical Theatres: A Critical Introduction can be used as a standalone text or together with its companion volume, Physical Theatres: A Critical Reader, to provide an invaluable introduction to the physical in theatre and performance.

New to this edition:

- a chapter on The Body and Technology, exploring the impact of digital technologies on the portrayal, perception and reading of the theatre body, spanning from onstage technology to virtual realities and motion capture;

-

- additional profiles of Jerzy Grotowski, Wrights and Sites, Punchdrunk and Mike Pearson;

-

- focus on circus and aerial performance, new training practices, immersive and site-specific theatres, and the latest developments in neuroscience, especially as these impact on the place and role of the spectator.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Physical Theatres by Simon Murray, John Keefe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Genesis, Contexts, Namings

Letter to a young practitioner

Value the work of your hands and body

This physical body is the meeting place of worlds. Spiritual, social, political, emotional, intellectual worlds are all interpreted through this physical body. When we work with our hands and body to create art, or simply to project an idea from within, we imprint the product with a sweat signature, the glisten and odour which only the physical body can produce. These are the by-products of the meeting of worlds through the physical body. It is visible evidence of work to move from conception to production. Our bodies are both art elements and tools that communicate intuitively.

Goat Island: C.J. Mitchell, Bryan Saner, Karen Christopher, Mark Jeffery,

Matthew Goulish and Lin Hixson.

(From Maria Delgado and Caridad Svitch (eds) (2002: 241), Theatre in Crisis?, Manchester University Press)

Contemporary contexts

The singular ‘physical theatre’ has had a popular currency among theatre publicists, critics and commentators in the UK, North America and Australia over the past thirty years. Eight years after our first edition it still remains a term which many young theatre companies and artists are prepared to use as part of a rhetoric that aspires both to encapsulate their practice and to sound fashionable, ‘modern’ and exciting to potential audiences. Regardless of whether the phrase actually describes, reveals and delineates theatre practices in any productive way, that certain practitioners, arts promoters and publicists should choose to use and propagate this term – or variations on it – tells us something significant about the times we live in. To be ‘physical’ in theatre is apparently to be progressive, fresh, cutting edge and risky, while at the same time it is a distancing strategy from a range of theatre practices that are perceived in Peter Brook’s phrase to be ‘deadly’ (Brook 1965: 11), outmoded and laboriously word based. To be physical is to be sexy and to resist the dead hand of an overly intellectual or cerebral approach to theatre making. To be physical in performance connects you to territories not regularly associated with theatre – with, for example, sport (see PT:R), dance and club culture and (more theoretically) with contemporary discourses that articulate and rehearse the nature of embodiment in a wide range of public, personal and intellectual spheres.

We are even more aware in 2015 that the field of enquiry represented by this book connects closely to – and overlaps with – a number of other published accounts of the past two decades that have sought to map changes and developments in Western theatre practice from the 1960s into the twenty-first century, and to identify the characteristics of new theatre forms and aesthetics. The writings of, for example, Hans-Thies Lehmann (2006), Philip Auslander (1997, 1999), Tim Etchells (1999), Matthew Goulish (2000), Elinor Fuchs (1996), Deirdre Heddon and Jane Milling (2005), Jen Harvie and Andy Lavender (2010), Jen Harvie (2013), Josephine Machon (2013) and Alex Mermikides and Jackie Smart (2010) have all in their different ways traced shifts in modes of performance or acting, relations with dramatic texts and dramaturgical and compositional strategies. A publication entitled A Performance Cosmology (2006) marking 30 years of the Centre for Performance Research (CPR) (see Chapter 4) is an eloquent and emblematic statement that captures many of the preoccupations and focal points of theatre and performance writing over this period. It particularly characterises contemporary concerns felt by a number of commentators that how one writes about theatre and performance is as important – and problematic – as what one writes. Since our first edition there have also been a number of publications (Radosavljevic (2013) and Britton (2013)) exploring (and celebrating) the ideas, practices and difficulties of ensemble work much of which has been driven by an explicit concern with the theatre languages of action, movement and gesture.

Connections and differences with some of these analyses will emerge as our own narrative unfolds, but at this point it is worth remarking that all these accounts note an increase in the role of the visual languages of theatre and a loosening of the relationship between dramatic text and performance composition. This sense of a slackening of the grip of historically dominant models of theatre formation does not in itself demonstrate the emergence of a new overarching paradigm, although Hans-Thies Lehmann’s proposition of ‘postdramatic theatre’ comes close to this. Indeed, as Lehmann himself argues:

At the same time, the heterogeneous diversity of forms unhinges all those methodological certainties that have previously made it possible to assert large-scale causal developments in the arts. It is essential to accept the co-existence of divergent theatre forms and concepts in which no paradigm is dominant.

(Lehmann 2006: 20)

Whilst Lehmann’s model of the ‘postdramatic’ may have lost some of its immediacy and surprise it remains an important way of positioning and conceptualising contemporary performance and certainly our new sections (circus, site-specific and immersive theatre) and chapter on technologies in this second edition benefit from being read and decoded through the lenses of the postdramatic. Within these broader changes we are attempting to locate the changing role of the actor’s body and the extent to which contemporary theatre has foregrounded physical expressivity and gestural composition as the main signifying drives for the work in question.

Chapter 2, ‘Roots: Routes’, traces the complex historical lineage of our inclusive models of physical theatre and the physical in theatre. While here we have argued for a deep historical framing and recognition of corporeal performance practices, conventional wisdom often suggests that physical theatre was a startling new departure in forms of theatre dating only as far back as the 1970s and 1980s.

Namings

In Britain, the term ‘physical theatre’ first came to public attention through the emergence of DV8 Physical Theatre in 1986 (but note our extended historical timeline explored in Chapter 2). Slightly earlier, in 1984, the London-based Mime Action Group (MAG) was founded, and in its first newsletter (autumn 1984) Nigel Jamieson refers to ‘physical based theatre’ in response to the Arts Council’s recently published report ‘The Glory of the Garden’. By its third newsletter (Spring 1985) a MAG editorial refers to ‘mimes or physical theatre people’. We return to the role and development of MAG later in this chapter. However, the genealogy is more complex and convoluted than this, as the term ‘physical theatre’ seems to appear in various places throughout the 1970s and, Baz Kershaw suggests, was possibly part of the rhetoric used by Steven Berkoff and Will Spoor in the London-based Arts Lab of 1968 (Standing Conference of University Drama Departments (SCUDD) email exchange, April 2006). Certainly, the term is invoked as a shorthand to identify a range of practices associated with Grotowski’s laboratory, and DV8’s Lloyd Newson acknowledges this legacy in an (unpublished) interview with Mary Luckhurst in 1987 (www.dv8.co.uk). The term can also be traced in Peter Ansorge’s book, Disrupting the Spectacle, where there is a suggestion of an American derivation:

Nancy Meckler, as the American creator and director of Freehold, has been generally recognised as the most successful exponent in this country of the US-inspired style ‘physical theatre’ which was perhaps illustrated most succinctly by her adaptation for Freehold of Sophocles’ Antigone.

(Ansorge 1975: 23)

While explicit usage of the term does not seem to pre-date 1968 at the earliest, it is a central contention of this book that there are theatre practices down 2000 years of theatre history that might conceivably have claimed, or been ascribed, the physical theatre appellation had the terminology been culturally available. As we argue throughout this book, the work of such diverse twentieth-century Western theatre practitioners as Meyerhold, Artaud, lonesco, Brecht, Beckett and Littlewood could be described, albeit through a different lens, as ‘physical theatres’.

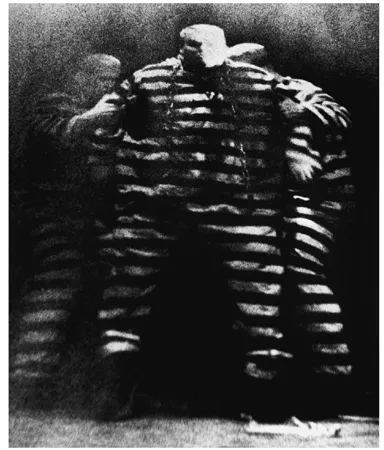

Figure 1.1 King Ubu (1964) (Alfred Jarry), Theatre on the Balustrade, Prague, Czechoslovakia. Copyright: Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

However, notwithstanding sporadic sightings of the term in the 1970s, it is not until the mid-1980s that the phrase begins to gain some momentum and becomes a fashionable designation for a range of emerging practices. Although DV8’s company name is still officially DV8 Physical Theatre (see website), it is no longer a term that Lloyd Newson finds useful because ‘of its current overuse in describing almost anything that isn’t traditional dance or theatre’ (www.dv8.co.uk). We look at DV8 in more detail in Chapter 3, but at this moment we may note that since its launch 20 years ago, Newson has talked of the company’s work as ‘breaking down the barriers between dance, theatre and personal politics’ and of ‘taking risks, aesthetically and physically’ (ibid.), saying that this mode of description is not untypical of how other companies begin to identify their practice.

Théâtre de Complicité, renamed simply Complicite in 2006, and founded three years before DV8 in 1983, has never claimed the term to describe its practice, and indeed has been hostile to having its work labelled in this way. None the less, Complicite, for better or worse, has often been regarded as the quintessential ‘physical theatre’ company to emerge in the mid-1980s. Complicite describes its principles as ‘seeking what is most alive, integrating text, music, image and action to create surprising, disruptive theatre … what is essential is collaboration. A collaboration between individuals to establish an ensemble with a common physical and imaginative language’ (Complicite website: www.complicite.org).

David Glass has been performing internationally – initially as a solo mime artist – from a base in the UK since 1980, but established his own ensemble in 1990. Glass describes his practice and that of the ensemble as ‘committed to imagination and collaborative theatre, rooted in the alternative traditions and skills of physical and visual theatre’ (David Glass Ensemble website: www.davidglassensemble.com). In 1979, Desmond Jones established in London what he initially and unapologetically described as a ‘mime school’, but from the mid-1990s this had become a ‘School of Mime and Physical Theatre’.

By 1989, five years after its launch, MAGazine – the journal of Mime Action Group (founded 1983) – had metamorphosed into Total Theatre (The Magazine for Mime, Physical and Visual Theatre) and this banner very quickly began to take visual precedence over ‘Mime Action Group’ in most of the organisation’s transactions. Now into its fourth decade Total Theatre has pared back its work to producing an online information source (including its journal, also called Total Theatre) and to enable the annual ‘Total Theatre Awards’ at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Today Total Theatre says of itself:

We resist too narrow a definition of the term ‘total theatre’ but through both these projects honour artists and companies leading innovative work within physical, visual and devised theatre, dance-theatre, mime/clown, contemporary circus, cabaret and new variety, puppetry and animation, street arts and outdoor performance, site-specific theatre, live art, hybrid arts/cross-artform performance – and more.

(Total Theatre 2015)

Thus, over a comparatively short period, mime is supplanted – willingly or not – by ‘physical and visual theatre’ and is relegated to stand alongside, for example, puppetry, mask and street performance. In the mid-1980s, for David Glass and – especially – Desmond Jones this represented a diminution and a weakening of everything they believed mime represented. Jones took these arguments into the pages of the MAG newsletter and the early issues of Total Theatre in a number of witty, joyful but scabrous polemics against those who would dilute the art of mime for what he believed was a nebulous and bland ‘physical theatre’:

I am convinced that Mime will change the face of the speaking theatre in the next 25 years. Maybe not mind-numbingly staggeringly, but significantly. People will come to us, are coming to us to learn our techniques … . We do mime. No pissing about. If we are strong people will come to us. We are going through an identity crisis, certainly … Krakatoa was a squib compared to what has happened in Mime in the last 9 years.

…

I do Mime

What do you do?

Stand up and be counted.

(Jones, MAGazine, Spring 1985)

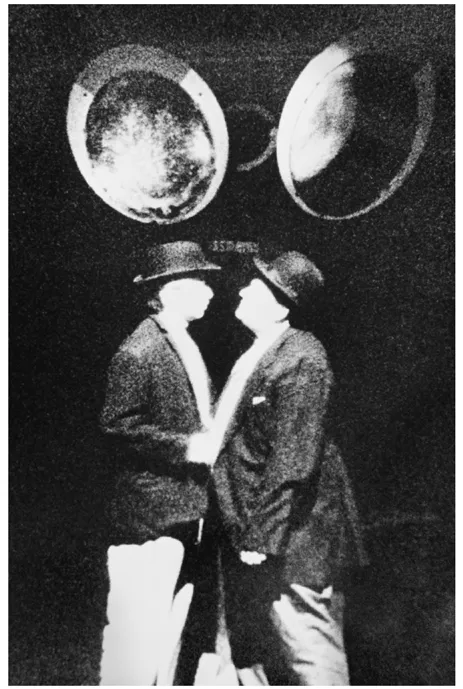

Figure 1.2 Waiting for Godot (1964) (Samuel Beckett), Theatre on the Balustrade, Prague, Czechoslovakia. Copyright: JK/Magnum Photos

We could extend this type of mapping exercise to hundreds of companies, agencies and theatre practitioners emerging in Europe, Australia or North America during the 1980s and 1990s and find similar constellations of key words and phrases. In Australia since the 1980s there has been an equally burgeoning theatrical movement which seems to have embraced the physical theatre appellation with less awkwardness than its UK counterpart. Our book regrettably cannot do more than signal these energies in Australia and observe that there is a study in waiting which might usefully explore the cultural and dramaturgical particularities of Australian physical theatres. For now we can note the useful section in Heddon and Milling’s Devising Performance (2006) on Australian physical theatre practices. Heddon and Milling observe throughout their book that late twentieth-century devised theatre has consistently been preoccupied with the shifting politics of personal and cultural identity, and that this has been especially the case in Australia. They suggest that physical theatre practices there have sharply articulated a celebration of diversity in Australian social life, a diversity that has partly been driven by a developing desire for distance from many of the smothering and colonialising cultural forces of Europe and Britain in particular. ‘Today’, as Heddon and Milling remark, ‘this body-based devising draws more fully on Asian and Pacific Rim cultures and practices, most fully exemplified by the popularity of Butoh and the use of Suziki training’ (Heddon and Milling 2006: 164). Formally, circus and dance conventions impacted strongly on many of the earlier Australian physical theatre practices, although today – as in Europe – many of the new companies are perhaps more likely to look towards the proposit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction to second edition

- Introduction

- 1 Genesis, Contexts, Namings

- 2 Roots: Routes

- 3 Contemporary Practices

- 4 Preparation and Training

- 5 Physicality and the Word

- 6 Body-Stage-Theatre Technology

- 7 Bodies and Cultures

- 8 Conclusion by way of Lexicon

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index