![]()

1

Introduction

Situating prejudice and education

Introduction

Prejudice and education are inextricably linked as they both touch on the most fundamental attribute of human behaviour: learning to live together. A good education will teach a person to judge other people with some degree of intellectual, moral and social retinue whereas one could argue that an education would have failed were it to leave us with people who generalise about others easily, judge others harshly on little but assumptions and dislike individuals or entire groups of people without even knowing them. To behave this way would imply that lessons of good judgement and understanding have been futile, lost or never taught.

It seems even more crucial today than before to educate for less prejudice as social tensions rise, world demographics swell and violent words and actions become increasingly widespread. In an increasingly uncertain global environment, an analysis of what prejudice is, what works to reduce it and how this might be done through educational strategies is prescient. This chapter discusses these questions by summarising topical, historical and theoretical positions, facts and trends so as to give the reader an overview of the relationship between education and prejudice.

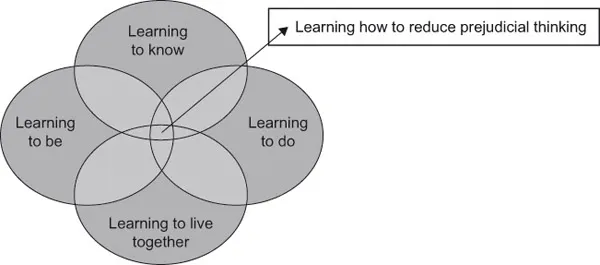

The purposes of an education

What is an education for? This is a question that has plagued philosophers and educators for at least two and a half thousand years. There are constants that have run through systems and cultures since the earliest known educational philosophies that come to us from Socrates and Confucius: on the one hand, education has always been about the transmission of knowledge; on the other hand, the inculcation of values. A third area, between the two, that educational systems have always aimed to develop, is what we could call skills or competences. These three areas only mean something when put into the context of a fourth area: what it means to actually live them out and apply them in the real world. These four areas of learning were made clear in the 1996 UNESCO Delors report, which described the overarching purposes of education as ‘learning to know, to do, to be, and to live together’ (Delors et al., 1996). In other words, learners should appropriate knowledge, learn how to apply knowledge, to self-regulate and behave in society.

FIGURE 1.1 Learning to reduce prejudicial thinking: at the core of the four pillars of education

What is prejudice?

Prejudice lies at the intersection of all four pillars of learning in that it draws on them for its development and reduction. The etymological root of the word prejudice is the Latin praejudicium, meaning ‘precedent’ (Allport, 1954, p. 6), but in a modern sense the term more accurately denotes a priori, unwarranted and usually negative judgement of a person due to his or her group membership: it is a ‘unified, stable, and consistent tendency to respond in a negative way toward members of a particular ethnic group’ (Aboud, 1988, p. 6).

Prejudice comes about because of the mind’s necessary categorisation of experience into information through language, thus simplifying and labelling phenomena to make them more easily manageable. This can lead to stereotyping and over-simplification, especially when dealing with human beings and the social categories we might use to define them (gender, ethnic origin, creed, nationality, class, political beliefs). Stereotyping becomes prejudice when it is hardened into a stable, judgemental and negative belief about individuals based on perceived properties of the group to which they belong.

Pettigrew and Meertens (1995) have suggested that one can distinguish between ‘subtle’ and ‘blatant’ prejudice; the former being more insidious, carefully justified and therefore less easily detectable than the latter.

Prejudice and learning to know

At a cognitive level, therefore, prejudice comes about when there are problems with learning to know: it is a cognitive bias that stems from over-generalisation (Allport, 1954, pp. 7–9). Some studies suggest that the prejudiced person has lower cognitive ability and overgeneralises in cognitively challenging situations such as ambiguity (Dhont & Hodson, 2014). Concepts associated with this over-generalisation include the ‘illusory correlation’ (perceiving unfounded or untrue relationships between groups and behaviours) and the ‘ultimate attribution error’ (mistakenly attributing negative traits to entire groups) (Pettigrew, 1971). Devine (1989) outlined a two-step model of cognitive processing whereby initial stereotype formation needs to be tempered with a conscious, cognitive effort. As such, reducing prejudice requires cognitive functioning that resists ‘the law of least effort’ (Allport, 1954, p. 391).

Prejudice and learning to be

As concerns learning to be, prejudice is linked to a lack of careful self-reflection as it tends to be self-gratifying in its function (Allport, 1954, p. 12; Fein & Spencer, 1997); it is a ‘will to misunderstand’ (Xu, 2001, p. 281) that one uses to protect a ‘deep-seated system of emotions’ (Thouless, 1930, p. 146). Prejudice frequently masks fear and/or anger, often with the self and as such masks ‘beliefs held on irrational grounds’ (Thouless, 1930, p. 150). Fiske et al. (2002) have suggested that stereotyping tends to be predicated by strong emotional states ranging from pity and sympathy to contempt, disgust, anger and resentment (p. 881). Therefore, reducing prejudice implies a degree of self-regulation and self-criticism.

Prejudice, learning to live together and learning to do

Prejudice is a strong, hasty over-generalisation of an individual or group that tends to be negative in character. This means that the social interactions that follow tend to make learning to live together difficult because relationships are predicated by mistrust. In its most well-documented forms (racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, snobbery and bigotry), prejudice implies deficient models of social interaction based on feelings of antipathy that stand in the way of constructive dialogue, collaboration or common goals.

Prejudice can affect knowing to do since it is an active, virulent over-generalisation that implies action. This is one of the points that differentiates prejudice from stereotyping since stereotypes are merely representational – they are ‘pictures in the head’ (Lippman, 1922) of individuals or societal fabric. According to Fiske et al.’s stereotype content model (2002, reviewed in 2008 by Cuddy et al.), stereotypes tend to be articulated along a warmth–competence axis, meaning that groups tend to be essentialised in terms of a number of combinations as either warm (friendly, close) or competent (clever, high-performing). Prejudice, on the other hand, is not just a cold thought but an emotionally driven attitude that can lead to acts of discrimination and violence.

Allport suggested a scale of prejudice that goes from ‘antilocution’ through ‘avoidance’ and ‘discrimination’ to ‘physical attack’ and finally ‘extermination’ (1954). This would suggest that reducing prejudice means reducing strong feelings of antipathy to outgroups and/or members of those groups before these thoughts translate into actions. Dovidio et al. (1996) point out that empirical research suggests that this is only moderately true.

Why is reducing prejudice so important?

This book argues that efforts to reduce prejudice are of huge import to the fundamental enterprise of education. Prejudicial thinking spans the four pillars of education as does aiming to reduce it.

In the table below I have listed, under the four pillars of learning, facets for each that display less and more prejudiced mindsets. A good education will take learners from more to less prejudiced mindsets as this will develop higher levels of cognitive, affective and social competence.

The role of education is to take human beings from states of ignorance, intuitive and unfounded understanding and unskilled ability to higher levels of knowing, thinking and doing. This is why Socrates said that ‘knowledge is virtue’: knowledge brings with it a moral conscience that predicates how we behave. In theory, a good education should temper prejudiced thinking as it should teach learners to think twice, to suspend judgement, to keep an open mind, to better understand others and the self and to act in constructive, civil ways for the betterment of humanity – we come back to the four pillars of the UNESCO Delors report (1996).

TABLE 1.1 Prejudice and the Delors report More prejudiced mindset | Less prejudiced mindset |

Knowing selectively | Learning to know |

Poor understanding of context: ‘will to misunderstand’ | Domain, cultural, historical and propositional knowledge and deep, conceptual understanding of systems, contexts and facts |

Over-generalisation and lack of nuance of theory | Knowledge of theory |

Knowledge is put to negative practice | Practical knowledge |

Inability to critically self-examine | Metacognition (knowing how we know and learning how we learn) |

A priori judgement, rationalisation of negative, emotions, little reflexivity | Critical thinking (reasoning, inference-making, judgement, hypothesis testing, reflective thought) |

Narrow transfer in the form of judgement of the individual in terms of the group and the group in terms of the individual | Transfer of knowledge |

Fixed, narrow thinking, inability to imagine the world otherwise | Imagination, divergent thinking, creative thinking |

Selective memory, refusal to accept disconfirmation | Short and long term memory functioning: information storage and retrieval |

Over-generalisation | Synthesising |

Learning to do with prejudice | Learning to do |

Prejudicial and sometimes unethical behaviour | Ethics: doing the right thing |

Tends to blame outgroup rather than look for solutions | Problem finding and problem solving |

Inflexibility | Adaptation |

Learning to be (and to stay) prejudiced | Learning to be |

Aggressive, obsessive, defensive thought | Mindfulness |

Resilience in the name of prejudice | Resilience (particularly to remain open-minded and accepting of others) |

Motivation for prejudice | Motivation (to dispel prejudiced inclinations and to suspend judgement) |

Lack of interest in outgroup beyond erected stereotype | Curiosity in other people |

Lack of wisdom since prejudice leads to conflict | Wisdom (understanding the value of respect and understanding across frontiers) |

Faith in a prejudiced set of beliefs and lack of faith in other people | Faith in other people’s potential |

Unfair, unbalanced judgement | Balance: temperance |

Lack of control of strong emotions and intuitive reasoning | Discipline |

Negative emotions which can lead to violence | Health (striving for productive, healthy relationships) |

Lack of care for victim of prejudice | Responsibility |

Frustration, anxiety, anger | Happiness |

Feeling of dispossession, potential leadership in scapegoating and othering | Positive, inclusive leadership |

Low self-esteem disguised by outwardly directed anger | Self-confidence |

Lack of sensitivity | Emotional intelligence |

Learning to live apart | Learning to live together |

Selfish or exclusively in-group sense of community and service | Community and service |

Conception of ‘civil’ as exclusive and conditional | Civic education |

Closed-mindedness | Open-mindedness |

Difficulty or inability to listen to the views of targeted outgroup members or counter-claims | Communication and social skills (interpersonal intelligence, the art of listening) |

Disrespect | Respect |

Meanness | Kindness |

Intolerance | Tolera... |