![]()

Part One

Introduction

![]()

1

Why Study Morality?

The strongest way to convey our disapproval of certain courses of behavior is to qualify them as ‘immoral’. Making people aware that their behavior is not morally approved should motivate them to change their ways. Yet this is not necessarily what happens. As behavioral scientists, psychological researchers have examined why this is the case. Results of their research help understand what makes people vulnerable to moral lapses, and why they may resist efforts intended to improve their moral behavior. These insights can help address and prevent the occurrence of ‘immoral’ behavior.

Moral judgements and moral concerns dominate public discussions of the most pressing social problems of our time. The Occupy Wall Street movement questioned the morality of people working in the financial sector. Their irresponsible and immoral behavior was seen as a major cause of the economic crisis that has affected individuals, businesses, national economies, and international relations since 2008. The events of September 11 and other terrorist attacks across the world have raised public debates about good and evil. There is concern about the moral legitimacy of detention and aggression against potential terror suspects as a way to secure national safety. Revelations about NSA surveillance practices and WikiLeaks remind us that privacy suffers and mistakes are made in efforts to protect the public. All these developments have also made clear that well-intentioned attempts to achieve desired outcomes can still cause suffering and harm. Likewise, concerns about the morality of current societal, economic, and political arrangements have been fueled by the Ebola epidemic, mass migration to ‘Fortress Europe’, and political instability of nations and international conflicts due to religious fundamentalism and intercultural differences.

At first sight, the solution seems simple. We should clarify the moral implications of different courses of action, and develop clear guidelines as to which behaviors are considered morally acceptable or unacceptable. Indeed, this is an important common thread in the public debate. Journalists give voice to the outrage and moral disapproval of the public in response to recent events. Policy makers emphasize the moral implications of business practices. Responsible parties point to legal provisions that need to be made. Attempts to change the behavior that has resulted in the current state of affairs include the introduction of a ‘banking code’, regulation for interrogation and detention of suspected terrorists, for instance in Guantanamo Bay, and appeals to different sectors to self-regulate. These all aim to convince those involved that change is needed by pointing to the morally questionable nature of their behavior.

Has this helped? Not really. Incidents of large scale cheating, corruption, and fraud continue to come to light, such as the manipulations of Euribor and Libor interest rates for personal gain in banking. But such incidents occur not only in the financial or business world. International cycling competitions turn out to have been plagued by wide scale doping use, as confessed for instance by Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong in a television interview with Oprah Winfrey. Match fixing turns out to be a regular problem in soccer tournaments in Europe, and is related to the activities of betting offices across the world. Respected scientists from different countries and in different disciplines have been convicted for plagiarism and large scale data fraud. The widespread occurrence and pervasiveness of such behavior that is generally considered immoral almost suggests people do not care about morality. But is this really the case?

It is not as simple as that. Yes, there will always be criminals who intentionally break the law and consciously harm others to maximize their own profit. But most of the time, the situation is not that clear. People who want to do the right thing are faced with difficult dilemmas. Situations are complex and multifaceted. We often face a trade-off between short-term benefits and long-term costs. People have to choose the least of two evils, decide under pressure and sometimes act unthinkingly – only realizing what the moral implications of their actions are after the fact.

As a result, the moral questions we face in daily life rarely are simple choices between right and wrong. Many of the current concerns regarding morality address such more complex issues. We rely on existing economic, legal, and political systems to provide us with guidance and to regulate the occurrence of acceptable vs. unacceptable behavior. So, we embrace the market economy, and endorse fair competition as a standard business practice. Yet we question the morality of the way hedge funds buy, break up, and sell companies as they sacrifice local employment and long-term viability for short-term financial profit. We are creative in finding ways within the law to reduce the amount of tax we have to pay. Yet we question large companies that benefit from legal loopholes to increase their profits. We strongly believe in the power of democracy and in the justice of majority vote. Yet we are outraged when democratic principles support measures that make many people suffer to protect the privilege of few.

And what should we do when different moral goals and values that we consider equally important are not compatible with each other? How do we reconcile entitlement to national and political sovereignty with appeals to our solidarity from citizens in Syria? What should we do if freedom of religion prevents the protection of children from lifestyle choices that can be seen as harmful? When do we allow concerns for the physical safety of many to overrule basic human rights of some? Do means always justify ends? Are people exempt from blame for the suffering of others if only their intentions are good?

These are the real questions that we face.

How we think of immoral behavior

The public debate has yielded a number of references to the alleged psychology of moral behavior. Journalists and other analysts taking this perspective have mainly argued for a consideration of the specific features that distinguish perpetrators of immoral deeds from ‘regular citizens’.

A documentary programme in the Netherlands on unethical business conduct in the banking sector (‘VPRO Tegenlicht’) interviewed different professionals making the case that banks attract individuals who suffer from all manner of psychopathologies in the autism spectrum. Experts characterized those making irresponsible financial decisions as psychopaths, autists lacking empathy, or nerds keen on getting back at those who bullied them in school for their lack of social skills.

Other analyses have emphasized the selfishness of key figures and corrupt leadership of individuals in politics and business. This also is the way commercial businesses and the banking sector in particular are portrayed in film. To explain recent developments in the financial and business world, many have cited the main character Gordon Gekko from the 1987 movie Wall Street who suggests that it is good to be greedy, because this has evolutionary survival value. The movie The Wolf of Wall Street provides a more recent account of this outlook on life.

A similar response was shown to the maltreatment and abuse of prisoners in the Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad, which came to light in 2003. Public shock and outrage was directed at the depraved individuals who perpetrated such atrocities. The soldiers involved were dishonorably discharged and punished. The common thread connecting these very different cases is the notion that immoral behavior was shown by specific individuals. The primary response therefore was to punish and remove these ‘bad apples’ to curb further problems. But are these questions of ‘bad apples’ only, or is it possible that we also have ‘bad barrels’ deserving closer scrutiny (Kish-Gephart, Harrison, and Treviño, 2010)?

The Dutch journalist Joris Luyendijk who trained as a cultural anthropologist, was assigned by the British newspaper The Guardian to get an ‘inside story’ of the financial world. From 2011 to 2013 he interviewed people working in the City of London for his ‘voices of finance’ series. He reported on his observations in his ‘banking blog’ (www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/joris-luyendijk-banking-blog; see also Luyendijk, 2015). On the one hand, this confirmed some of the common notions that work in the financial sector attracts greedy individuals, whose main concern is to compete with others for the best clients and the largest bonuses. On the other hand, some of his interviews cite family members and spouses who comment on how much their loved ones changed, after they started working at the bank.

The picture that emerges from the interviews with bank employees shows the corrupting effects of the typical incentive structure in finance. Interviewees comment that: ‘things would change if we linked bonuses to mistakes’, and that ‘the most dishonest bankers walk away with the most money’. They note the failing leadership, when they say: ‘outsiders see greed… I see bad management’. They also point out the self-selection of employees that fit the dominant business culture, commenting that ‘the sort of people you would want to work in a bank are being driven away’. When Luyendijk talks to an executive coach who works with bankers, she tells him: ‘what banks are offering people is an identity’. Together, these interviews suggest that situational factors, such as the incentive structure and type of leadership, as well as the corporate culture and identity play an important role in attracting and retaining those types of people, and rewarding those types of behavior that contribute to questionable business practices and irresponsible risk-taking.

These observations resonate with common concerns permeating the public debate: Even if greedy individuals are attracted to the financial sector, is it wise to further fuel such greed with perverse performance incentives? And surely if security officials transgress guidelines for the treatment of prisoners or suspects, this also points to the lack of supervision and (legal) regulation of acceptable interrogation techniques? This would seem to call for a deeper analysis of the string of events leading up to publicized transgressions, and broader concern for the general context and ethical climate that allowed these excesses to happen.

The call for change at this level is easily made. Preventing the reoccurrence of problems that have come to light also requires scrutiny and adaptation of the organizational ethical climate or the culture of accepting violence among security personnel. But how can this be achieved? The function of culture – and organizational cultures too – is to preserve traditions, transmit knowledge, and to provide stability, even in times of change and with rotating personnel (Bradley, Brief, and Smith-Crowe, 2008; Schneider, Ehrhart, and Macey, 2013). Guidelines for acceptable and unacceptable behavior are based on explicit and formal regulations, but are translated and communicated through informal hearsay and implicit rules of conduct. This makes it very difficult to capture or pinpoint concrete elements of culture that contribute to or condone immoral behavior. It certainly makes the task of achieving change at that level seem daunting – if not hopeless.

Indeed, banks that were only just saved by the State – at the expense of taxpayers – have substantially increased rewards of their CEOs, allegedly to ensure their corporate standing and ability to attract and retain high quality personnel. In the Netherlands this happened, for instance, at ING and ABN/AMRO, only weeks after State support was terminated, and while extensive job cuts among lower level personnel were still ongoing (source: NRC March 20). Huge bonuses are also back on Wall Street. A report of the Institute for Policy Studies (Anderson, 2015) revealed that in 2014 the bonuses of 167,800 Wall Street employees were 27% above the level of 2009, the year after the banking crisis started. This was also the last year that minimum wages were increased by the US Congress. At the same time, this report notes that financial reform laws prohibiting bonuses that encourage ‘inappropriate risk taking’ have still not been implemented by regulators, ignoring ‘key lessons from the last half-dozen years of financial scandals’ (p. 3). Yet there also are some examples of attempts to meet this challenge head on. The Dutch Central Bank (DNB) was the first in the world to explicitly extend supervision to behavior and culture (IMF Global Stability Report, 2014), and employed a team of psychologists for this purpose (Nuijts and De Haan, 2013).

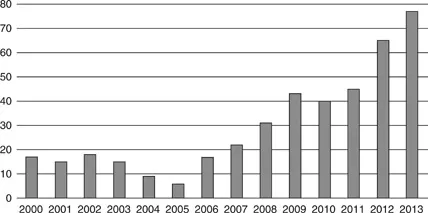

When we move away from the public debate to see what science has to offer in this respect, there too the evidence seems to be mixed. There is lack of consensus about why people display immoral behavior, or how to address this. Different approaches and analyses have been proffered stemming from philosophy and virtue ethics (Appiah, 2008; Hursthouse, 1999), biology (De Waal, 1996; 2009), evolution science (Tomasello, 2009), neuroscience (Churchland, 2011), or organizational behavior science (Bazerman and Tenbrunsel, 2011). In my field, social psychology, research on morality has also abounded during the past years (see Figure 1.1). But if anything, this has made clear that there are no easy solutions. A review of over 400 empirical studies on morality shows that moral appeals easily backfire, that the introduction of moral codes is not always effective, that moral arguments evoke strong counter arguments, and that moral climates or cultures may benefit as well as undermine moral behavior (Ellemers, Van der Toorn, and Paunov, in preparation). Thus, a more fine-grained analysis is needed to see whether and how this work can inform public policies aiming to reduce immoral behavior.

Figure 1.1 Number of publications on morality in social psychology, 2000–2013

How do we examine moral behavior?

The interest of psychologists in morality as a topic of empirical inquiry has increased dramatically during the past years (see also Giner-Sorolla, 2012; Greene, 2013; Haidt, 2012). These have addressed a wide array of topics in moral psychology, that together cover the relevant themes of moral reasoning, moral emotions, moral self-views, moral judgements, and moral behaviors (see Figure 1.2, Ellemers et al., in preparation). Yet the research designs and methods that are most frequently used to examine these issues have been criticized for the over-representation of some approaches, at the expense of others (Abend, 2012).

For instance, a lot of what we know about moral decision making is based on choices people make in so-called ‘trolley dilemmas’. In these studies people are given the option to intervene in the course of a runaway train that is bound to run over people tied to the train tracks. Participants in such studies are requested to make decisions about sacrificing the lives of few to be able to save the lives of many (for instance by pulling a switch to make the train change tracks). A review of publications that had appeared between 2000 and 2012, identified 136 papers addressing such trolley problems. Undoubtedly, this has yielded important information about concerns and mechanisms that play a role in this type of moral decision making. Yet hopefully, most of us will never encounter such a situation in real life (see also Bauman, McGraw, Bartels, and Warren, 2014; Graham, 2014).

Furthermore, it has become clear that social desirability concerns and self-protective mechanisms play a role in guarding people against admitting (even to themselves!) that they can act immorally (Ariely, 2012; Shalvi, Gino, Barkan, and Ayal, 2015). This would seem to limit the conclusions that can be drawn from explicit self-reports of concerns, behaviors, or emotions. Yet many studies rely on people’s explicit statements about their moral characteristics or behavioral preferences in moral dilemmas (Ellemers et al., in preparation). For instance, there are a substantial number of studies that examine correlations between self-reported moral traits (e.g., honesty) and self-reported moral behaviors (e.g., the intention to be truthful). Does such work truly advance our insight in the origins of moral behavior, or does it primarily show that in self-reports trait measures correlate with behavior measures?

Experimental techniques that have been developed allow us to go beyond such self-reports. Potentially, there is a large array of implicit indicators that can be used to capture people’s moral judgements or behavioral inclinations. These include tests of implicit associations (IAT, word completion, or response latency measures), measures of cardiovascular arousal and hormonal changes to indicate stress and coping responses, or measures of eye movements or brain activity to indicate attention for specific types of information. Yet, there is only a small minority of studies that uses such indicators to assess people’s responses to morally charged situations (Ellemers et al., in preparation).

These methodological attempts to separate and analyse specific processes involved in moral behavior, as well as the differences in em...