![]()

Introduction

MORE so than ever before, humans access and exchange information effortlessly. In even the most remote reaches of the planet, any fact, figure, or contact number can be requested, and the information is returned instantaneously. And so every minute of every day, human interactions generate 204 million emails, 100,000 tweets, and 640 trillion bytes of data.1 The prediction of an information-based virtual reality – the forward-thinking notion of cyberspace discussed only 25 years ago – is no longer a high-tech fantasy, but a practical reality.2 As such, the broad extent and rapid rate of data transfer has redefined global culture, and transformed the tools and methods of architectural design.

At the core of this shift in architecture is the wide-scale adoption of Building Information Modeling (BIM) – the process by which a digital representation of a building’s physical and functional characteristics is created, maintained, and shared as a knowledge resource. Since the early 2000s, BIM has become a necessary part of new building construction. But as architects and other design professionals have grown familiar with the modeling process, concerns have arisen. BIM is an effective tool to support the practical aspects of construction – like standard documentation, project management, and sustainability – but this focus has led critics to fear that BIM is driving the “normalization” of architecture, suppressing design innovation, and sacrificing formal and spatial expression for procedural clarity and building efficiency.

In the contemporary information-space, practitioners have the capacity to explore and incorporate large quantities of data in their work. Armed with new technological advances, the discipline of architecture is working to understand the broader implications for design and how the outcome of this shift from traditional industry to an ever-changing, information-based architecture sufficiently describes, guides, and executes the dynamics of a modern, complex society.

Beyond BIM explores the vast design potential of BIM. Trough a series of investigations grounded in the analysis of built work, interviews with leading practitioners, and speculative academic projects, this book catalogs the practical advantages and theoretical implications of exploiting BIM as a necessary tool for design innovation. Organized by information type, workflows, and material characteristics, each chapter defines a realm of knowledge that could be harvested for BIM, giving meaningful specificity to architectural form, space, and field. The work documented and envisioned in this book moves well beyond “normalization” to reveal inventive takes on contemporary practice.

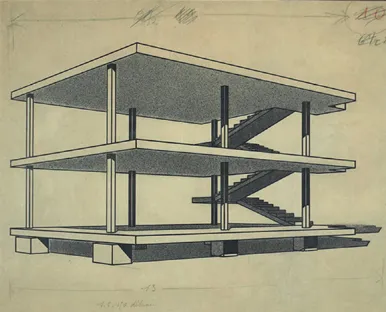

Le Corbusier Maison, Domino (1914 Plan FLC 19209A © F.L.C./ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2014)

Building

When considering the meanings behind the BIM acronym, “building” sets up a predicament from the perspective of design. As much as the discipline is in need of a construction protagonist – one that can strengthen the alleged declining relationship between architect and contractor and the general building organization – no one wants to produce just a building. The term has become a pejorative, associated with the most meaningless ways to cover space, like cheap commercial buildings and sheds. In contrast, architects want to design masterly space and form – in other words, architecture.3 The discipline admires the act, not the artifact, of building. In this context, whereby orthogonal assumptions put forth nothing more than a box, “building” falls prey to the regularity of the datum and grid structure that is at the heart of the BIM construction plane. The nefarious nature of BIM lies in this conflict between building and designing.

Le Corbusier’s 1914 Maison Dom-ino proposal exemplifes an orthogonal system of procedural clarity and building efficiency, and in many ways it represents the criticism of BIM. When taken literally (as it often is), its reinforced concrete frame is deployed in support of “building” instead of liberating the wall, as was originally intended by the system. Architecture critic Jefrey Kipnis suggests a frequent mishandling of this framework, datum, and grid lines of inquiry in the potential design phase.4 By allowing the grid and datum to limit visionary thinking – or at the very least, some aspects of innovation – the corresponding ground plane could generate a standard datum of architecture. Confidence in the coordinate system and framework supplied by BIM makes crucial differences plausible to the planar condition and to the breakdown of building as a system of parts – column, beam, footing – related to the whole.

Information

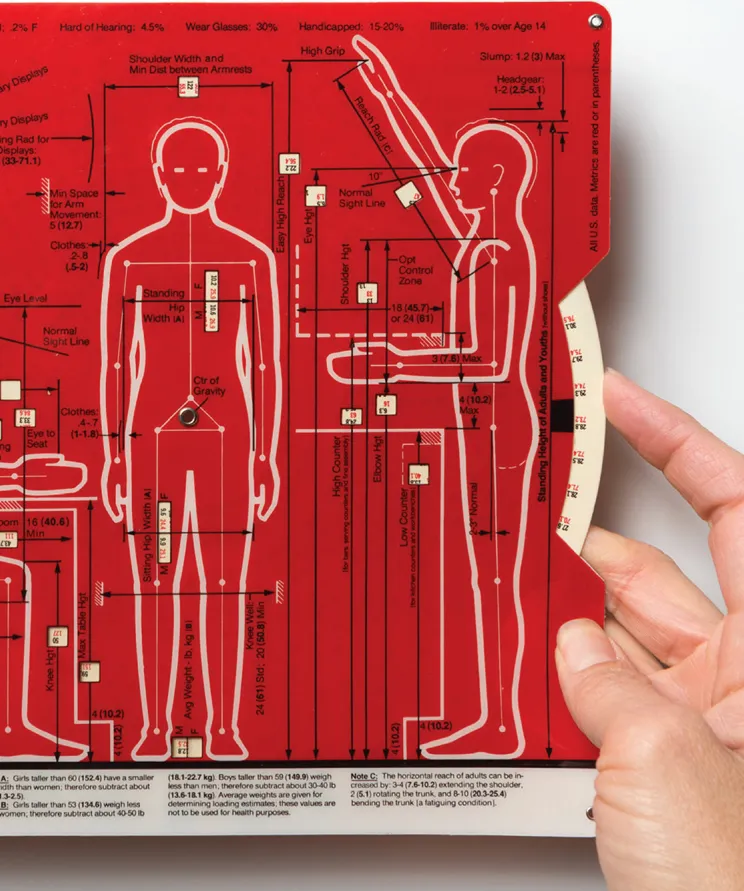

Historically, critical information for representing and creating architecture incorporated extensive amounts of human engineering data – compiled and disseminated in physical references and tools, such as Architectural Graphic Standards, Ernst Neufert’s Architects’ Data diagrams, and Henry Dreyfuss’s Human Scale–Body Measurement cards. The Human Scale hand cards are literally human scale, pictorial selectors equipped with rotary dials of information. Each card, which contains three selectors (two sides each) encompassing basic anthropometric guidelines for human proportions, offers specific ergonomic dimensions for age and gender demographics useful to a project at hand. The numerical values given in these documents represented at the time the most up-to-date research from anthropologists, psychologists, scientists, human engineers, and medical experts and held an authority in the design studio. The intention was to expand the notion of “form follows function” and to encompass the idea that human data has influence: “form follows function follows data.” For example, human physical measurements may dictate the design of a particular spatial function related to ergonomic activity, like sitting at a desk.

By offering 20,000 bits of information, the Human Scale pictorial cards appeared to be full of possibility as “design tools.” These novel devices, with their toy-like, unique ability to determine values for data accessibility, inspired information-based design through gadgetry. Although they now serve as a precursor to the “parametric slider” (so commonly used in contemporary parametric design), the selectors offered up numerical values that ultimately relayed and promoted normative conditions. But what of the dynamic eccentricities of human movement, or bodies with atypical proportions? Rather than generating for difference, these historical data sets tended to frame critical dimensions as fixed standards, or as Nicholas Negroponte put it, “a demographic unit of one.”5

The emerging information paradigm in architecture supports design mediated by the ability of a designer to capture and employ information freely with the potential for innovation. The success that informational modeling and data visualization has been met with in science and other disciplines suggests that the potential advantages of incorporating infinite amounts of data available today into the design process far outweigh the dangers.6 Rather than viewing BIM as a liability, architects should re-conceive the platform as a tool for pushing their own, unique conceptual agendas, or those generating for difference. BIM has the potential to enhance the design process in ways that will transform the resulting architecture.

This position of information-driven design suggests a criticality of intuition in the conceptualization of architecture. The access to granular information would have at one time seemed unimportant, or difficult (if not impossible) to find or incorporate. And yet, current data-capture and input technology, with its hyper-sensitivity to what is minute or obscure, implies design opinion as it pointedly changes the way facts are generated, collected, and implemented in an architectural project. As seen in the work of MAP Architects during their Svalbard Architectural Expedition, contemporary practitioners are increasingly testing innovative design methods by creating data-recording devices to tailor the information to conditional specificity. Producing unique data sets, not just harvesting incomplete or generalized ones, gets to the heart of information’s usefulness to design. In the case of MAP Architects, one of the “design instruments” created a spectrometer by de-constructing a webcam. This instrument was intended to register “spectral information” responsible for the color and altitude of the aurora borealis. This data, paired with video and photographic recordings of the aurora, furthered the design team’s understanding of the processes that create the spectacle – processes that might now be co-opted for innovative architectural agendas.

Human Scale 1/2/3: Body Measurements (image courtesy of Niels Diffrient, Alvin R. Tilley, and Joan Bardagjy, MIT Press; Bk&Acces edition, 1974) Photo credit Whit Preston

Svalbard Architectural Expedition (image provided by MAP Architects, 2013)

Modeling

Much of the basis for form creation in the BIM environment can be mapped to the earliest patriarchal software developments. In the 1970s, computer-aided design (CAD) rendered design to drafted intentions of vectors of lines, points, curves, and planes. This platform, which emerged to address hand-drawing inefficiency and management discrepancy issues, escorted basic, orthogonal geometry into architecture. The process led to more rapid replication of partial drawings and a new by-product of layer management: drawings were graphically clear and offered ease of reproduction. Information, however, became more fragmented, and conflicts between documents increased. In this scenario where CAD vectors represented no intrinsic information (other than a definitive position and directionality on the x and y axes of the work plane), their input (like hand drafting), relied primarily on intuitive placement. As CAD systems were most powerful in standardized, modular, symmetrical designs, many designers and architects remained skeptical of CAD as a design tool, fearing these limited productivity features would have too strong an influence on their work. Similar fears have surrounded the emergence of BIM as another acronymic design tool.

Although a shift to the use of BIM is viewed as a fairly new way of discerning and producing architecture, Chuck Eastman described a similar building information model 40 years ago. In his article “The Use of Computers Instead of Drawings in Building Design,”7 what he then called a building description system (BDS) offered a virtual multi-view, architectural modeling system as an enabler of arrangements and three-di...