![]()

CHAPTER 1

PORT INFRASTRUCTURE: WHAT ARE WE TALKING ABOUT?

Thierry Vanelslander

1. INTRODUCTION

Ports are following the globalisation trend and are globalising too: hub ports are developing so as to accommodate the growing volumes of traffic; there is a trend towards privatisation and takeover by large international groups in handling and even in entire ports, including management; and ports are confronted with global shipping lines featuring both more extended networks and larger ships. This all means that the capacity that these ports need is, on average, increasing. An important part of capacity is composed of infrastructure, and that is the topic of this chapter. However, it is important first to clearly define what exactly is meant by infrastructure here, and how it is distinguished from other capacity elements. The magnitude of investment and maintenance amounts is given in section 2. section 3 deals with the constraints in choosing what infrastructure to put in place. In section 4, the issues of optimum capacity and congestion are referred to. section 5 addresses who is typically taking the initiative to invest in infrastructure in different port settings, with a link also from where the capacity needs originate. Finally, section 6 gives the current state of decided and planned port investment projects and their characteristics.

2. WHAT IS PORT INFRASTRUCTURE?

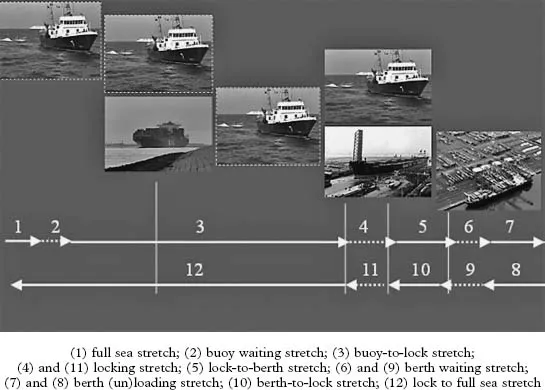

The route of a vessel calling at a seaport can be divided into several stretches. Figure 1.1 shows a general overview of such a seaport setting. A vessel that is on its way to a port can sail on several stretches, depending on the port setting as well as on its own characteristics or on environmental factors: starting with maritime transport at sea, part of a river or a canal can be used, further on there may also be a lock, until finally the docks will be reached. Once the ship is berthed, other activities can start: terminal activities such as vessel unloading/loading, storage and unloading/loading of hinterland modes. After this, the goods transformed will be moved to hinterland connections.

It is, of course, also possible to focus on movements in the opposite direction. The seaport setting is a general typology and can be applied to freight vessels and passenger vessels. It is certainly not necessary that every link is used in a specific port typology. Not all ports have locks, for instance.

Figure 1.1: Theoretical seaport setting

Source: own processing.

Infrastructure in one of the stretches from Figure 1.1 is now called port infrastructure. In general, we can say that this covers all long-term fixed capital investments (maritime entrance, locks, berths, gates, port authority offices, etc.). In the following paragraphs, the different infrastructure elements are detailed, focusing on the marginal cost character that each of them may or may not feature. Doing so will prove important and useful in section 4, where the decision to invest or not in additional infrastructure capacity will depend on the marginal cost function. Furthermore, it is also relevant to indicate the marginal character, as that shows from where the specific infrastructure need originates, being the basis for eventual pricing and/or investment (co-)financing requests.

The reason for the marginal cost approach is that currently there is a debate going on in many ports, in a quest for transparency, whether to shift from current pricing structures to more marginal cost-based ones. In most ports, pricing of an additional vessel is based on the sum of several pricing elements, each containing several constituent factors (Meersman et al. 2010). From a theoretical perspective, the pricing principle seems evident: all tariffs applied by and within the port should be based on the short-term marginal cost. On the other hand, it is sometimes asserted that ‘from a theoretical perspective, and assuming that a number of conditions are fulfilled, long-run marginal costs represent the most appropriate basis for efficient pricing’ (Haralambides et al. 2001: 939). Whether one should base the port pricing discussion on short-run or long-run marginal cost is still under debate. The argument in favour of the short-term marginal cost is that the whole point of pricing is to confront the user with the additional costs he or she causes. Only the short-term marginal cost indicates precisely the difference in costs between acceptance and refusal of an additional user (Blauwens et al. 2012). For that reason, the short-run marginal cost approach is followed in this chapter. section 4 gets back to the impact on capacity investment. In this case, the marginal cost is linked to an additional ship calling and, hence, for each infrastructure item it is asked whether it involves a cost that increases with the ship calling or not.

A start is taken at full sea. At the point where ships have to wait to enter the river or canal, the only infrastructure elements that could imply marginal costs are buoys, which are especially necessary to trace out the channel at sea. However, they are replaced on a regular basis. Neither their number nor the regularity of replacement is influenced by the number of vessels. Regularity depends solely on time: about every 18 months a buoy has to be replaced, since by that time natural overgrowth makes them less visible, so that maritime safety is negatively influenced and replacement is needed.

In the zone from buoy to lock, there are again several infrastructure items, but none have marginal components in a ship call. Breakwater expenses are considered to be independent of port usage (common costs; cf. Heggie 1974: 14). The same holds for navigation lights, which has been confirmed by the European Commission (1998: 10). For buoys in the buoy-to-lock zone, the reasoning for the maritime entrance waiting point is valid here, too. For maritime entrance banks, replacement does not seem to depend on the number of vessels passing by. Much more important is the natural streaming of the water: certain points of the bank need to be regularly fortified. For this reason the Flemish Department of Environment and Infrastructure states that marginal bank costs should not be considered. Confirmation of this statement is found on the website of the Scheldt Information Centre (2013).

Breakwaters may present a vertical, or near vertical, wall or a sloping surface composed of variously sized blocks, implying different costs and impact features. The two types are illustrated in Figure 1.2.

The radar system in the buoy-to-lock zone is a unique investment, the capital cost of which is again not influenced by an extra ship entering or leaving the port. Radar towers are often built alongside maritime entrance rivers. Data are processed at a central tower, from where control is assured through several screens operated by a fixed staff. In cases where a dangerous situation occurs, direct contact can be made with the ship, or ships, involved. This process implies that nowhere marginal costs are in place.

Concerning infrastructure maintenance, just like bank erosion, dredging is a cost item that is linked only with time and streaming of the river, and not with the number of vessels calling at the port. Short-run marginal costs of dredging are zero. The largest dredging effort is, of course, due when the port or terminal is being built. Depending on the amount of dredging work to be conducted, different types of equipment may be economically advisable, and hence lead to different costs (UNCTAD 1985).

In the locking zone, from an infrastructure point of view, there may be locks that may need replac...