eBook - ePub

Terms of Appropriation

Modern Architecture and Global Exchange

This is a test

- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection focuses on how architectural material is transformed, revised, swallowed whole, plagiarized, or in any other way appropriated. It charts new territory within this still unexplored yet highly topical area of study by establishing a shared vocabulary with which to discuss, or contest, the workings of appropriation as a vital and progressive aspect of architectural discourse. Written by a group of rising scholars in the field of architectural history and criticism, the chapters cover a range of architectural subjects that are linked in their investigations of how architects engage with their predecessors.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Terms of Appropriation by Amanda Reeser Lawrence, Ana Miljački in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Authorship

1

Signed, anonymous

The persona of the architect in the Mansion House debate

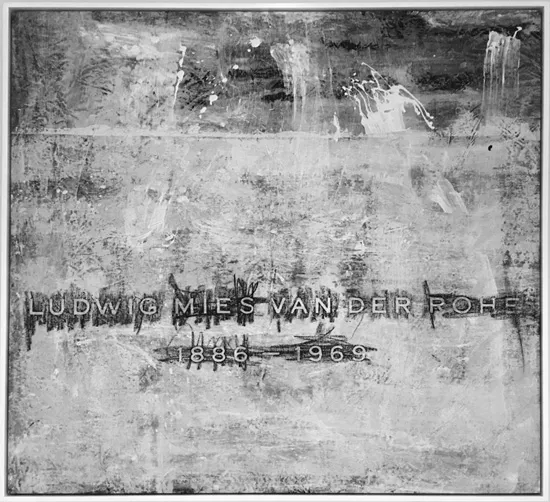

The death of the author is by now a familiar figural manifestation that opens into that sphere of textuality in which intention, significance, and meaning are diffused among the biographical fragments of a life lived; fragments disassembled and reassembled as interpretation, proposition, or possibility until the author as such has faded almost entirely from view. But we should not let the familiarity of this figurative death of the author encourage us to overlook its accompanying literal manifestation – the actual death of an author (Figure 1.1).

One such death occurred on August 17, 1969; the author in question was architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Mies was eighty-three years old, thirty years on from his arrival in the United States, ten years on from the completion of the Seagram building. From his office in Chicago, with a cohort of associates that included his grandson Dirk Lohan, Mies had overseen the final stages of work on the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and the more preliminary stages of several other projects. It is one of these latter projects, along with the persona of its architect, that competes for the central role of the story recounted here.

In 1958, the property developer Peter Palumbo (now Baron Palumbo of Walbrook) set out to purchase plots of land in the City of London in the blocks near Mansion House and the Royal Exchange. Four years later, in 1962, he commissioned Mies to design an office tower and an open plaza. Over the next several years, and with one visit to the site, Mies and his Chicago office developed a scheme for the tower and the plaza that Palumbo presented to the City of London planning authorities in 1968. This consultation with the authorities was required for several reasons, including the atypical height of the building and the alteration of existing street and traffic configurations, as well as the historical nature of the site itself. Mies’s tower was surrounded by the work of other well-known architectural authors – George Dance the Elder’s Mansion House and Edwin Lutyen’s Midland Bank would form two sides of the proposed plaza – and a number of less regarded though still authored Victorian buildings would have to be demolished to clear space for the tower (Figure 1.2).

The city authorities viewed the proposal favorably, but because Palumbo owned only some of the properties that were to be demolished, permission was withheld with an instruction that he first attain sufficient control over the relevant properties. Over the next fourteen years, Palumbo followed this instruction, buying a dozen freeholds and hundreds of separate leaseholds. Meanwhile, Mies’s office refined the design, and a set of working drawings was prepared and ready for presentation in 1982, the year that Palumbo returned to the Common Council of the Corporation of the City of London with almost all of the required property under his control.

Figure 1.1 Scott Covert, “Ludwig Mies van der Rohe” (2006). Rubbing of etched lettering on the tomb of Mies van der Rohe. Courtesy of Scott Covert.

By this time, now more than twenty years after Palumbo had conceived the project, a number of relevant circumstances had changed. With the rapidity of postwar reconstruction evolving into the rapidity of the development of the finance economy, new towers had appeared on the City of London skyline, and partially in consequence a trend toward preservation had emerged, so that the demolition of older buildings, even those of minor distinction, was now approached with greater hesitation. Conservation areas had been defined within the City, one of which contained parts of the proposed development, and some of the affected existing buildings had been listed – given various degrees of legal protection as either individual or grouped historic structures. More generally, a significant revaluation of architectural style had, in Britain as elsewhere, catalyzed a concentrated hostility toward modernist architecture paralleled by an increased veneration of English Victorian architecture (and of historicist architecture more broadly). At this point in time, Mies’s architecture would no longer be presumptively contemporary, nor would the existing Victorian commercial buildings be readily designated as insignificant or obsolescent.

Figure 1.2 Photomontage of the proposed tower block for the Mansion House Square scheme, 1 Poultry, City of London, 1983. Photograph by John Donat, courtesy of John Donat/RIBA Collection.

Palumbo’s renewed application now faced strong criticism, and was summarily rejected by the Common Council. Palumbo appealed the decision, prompting a review of the case by an appointed inspector with authority to gather information and opinions and then to convey a recommendation to the Secretary of State for the Environment. To carry out this process, and aware of the now considerable attention focused upon the proposal by the media and professional groups, the Inspector Stephen Marks convened a public inquiry held over ten weeks in 1984.1 This inquiry, while not an actual judicial proceeding, was nevertheless organized as one, with evidence presented by barristers and witnesses speaking in favor of or in opposition to the appeal through direct testimony and cross examination.

In this forum, the persona of the architect came distinctly into view, for of all of the changed circumstances since 1968, perhaps the most consequential was the fact that Mies had died in 1969. Despite Mies’s death, the design was still attached to his persona, and in 1984 this attachment assumed a considerable importance in light of the markedly diminished appreciation for the proposed development on the part of planning authorities. In order to make their case, Palumbo and his supporters – Richard Rogers, Colin St. John Wilson, James Stirling, and the historian John Summerson among them – placed Mies’s persona at the center of their argument. They pointed to his stature as one of the most important architects of the century and to the widespread appreciation of his realized works as evidence of the value of this prospective tower.2 They argued, in essence, that the City had an opportunity to construct a building by Mies, and the price to be paid was a collection of Grade II listed buildings by lesser-known architects.

While proponents of the scheme affirmed its architectural value by reference to its architect, opponents sought to undermine precisely this argument, first by stating that the architect’s reputation was less a historical determination than a “myth [that] had nothing to do with the actual quality of his buildings”;3 and second, by suggesting that the design could not be attributed to Mies with any certainty, due to the architect’s death and the absence of indisputable evidence of his hand in authoring the design. Where were the sketches or original drawings, asked John Harris, historian and founder of SAVE Britain’s Heritage.4 The building was yet another weak derivation of Mies’s iconic Seagram building, suggested Philip Johnson and Arthur Drexler. The historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock also indicated that Mies’s involvement could only have been at a preliminary stage.5

In short, the opponents argued that the building was not definitively bound to the person of Mies in biographical terms, and therefore did not possess in aesthetic terms the superior value claimed by its advocates. Forced to rebut this line of argument, Palumbo’s barrister brought to the inquiry Peter Carter, who was the job architect on the Mansion House Square scheme, and who had continued the development of this and other projects in the firm after Mies’s death. Carter assured the inquiry that the building had been designed with the full involvement of the famous architect, whose typical working method left little in the way of sketches or original drawings. He testified that Mies had known and approved of the revisions pending after the first application in 1968, and that any subsequent changes were minor and had no effect upon the appearance of the design.6

This dispute was not the only point of evidentiary contention during the Mansion House Square inquiry – much of which focused upon questions of conservation, heritage, and urban experience – but it is the issue I wish to pursue here. There’s no need for further suspense: following the inquiry and due consideration of the evidence, the Inspector recommended that Palumbo’s appeal be dismissed, the Secretary of State for the Environment agreed, and the Mansion House Square scheme joined the catalogue of unbuilt work.7 The evidence showed with rough equality that the design was by Mies and that it was not by Mies, an opposition that, as it took shape through the testimonies before the inquiry, ultimately suggested that the architectural person under scrutiny was not the living (or deceased) Mies van der Rohe, but the signature “Mies van der Rohe.”

An architectural drawing – the evidence of Mies’s authorship demanded by John Harris and other opponents – has long been regarded as an extension of the architect’s mind, functioning as an expressive object whose attribution enables the recognition of the architect to occur at a remove from a physical building or an actual body. Such distancing mechanisms within design (which might also include the separation of design from construction, or the collaborative nature of architecture firms) are familiar facts, even though they are most often veiled by personality. In 1984, the drawing had seemingly lost none of its standing to invoke the recognition of agency, but Carter’s testimony brought to the inquiry an exacting description of the same distancing figured not by the architectural drawing, but by discussion, review, approval, and other habits and conventions of architectural practice.8 His version, and the argument of non-authorship it aimed to rebut, removed the sphere of reference from personhood into signature.

The cartoonist Louis Hellman cleverly satirized the Corporation’s refusal of the scheme in 1982, with a mocking account in which Christopher Wren and his 1666 plan for the rebuilding of London stood in for Mies and his Mansion House Square proposal (Figure 1.3). (In Hellman’s cartoon, the then Secretary of State, Michael Heseltine, is made into King Charles II, and Peter Palumbo is the equally alliterative Christopher Columbo.) By associating Wren and Mies in this way, Hellman drew attention not simply to the stature of the latter (and the conservatism of his opponents) but also indirectly registered the suggestive presence of signature. For the parody here depends upon transposition – Mies’s head wearing Wren’s wig – which sets aside the determining details of biography for the more flexible characteristics of signature.

Though signature now inevitably invokes starchitects and their signature buildings, the architect as brand is only one narrow manifestation of signature, which I propose might be understood more usefully as the translation of personhood into a medium other than the actual person.9 In the case of Mansion House Square, one such manifestation would have been the legal attribution of liability, which, had the design been constructed, would be assigned not to Mies as an individual person, but to his incorporation as an architectural office or to the licensure of the name stamped upon the working drawings. Other manifes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: authorship, transfer, rights, re-enactments

- Part I Authorship

- Part II Transfer

- Part III Rights

- Part IV Re-enactments

- Index