eBook - ePub

Maritime Southeast Asia to 500

Lynda Norene Shaffer

This is a test

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Maritime Southeast Asia to 500

Lynda Norene Shaffer

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A history of the fabled islands of Southeast Asia from 300 BC, by which time their inhabitants had learned to sail the monsoon winds, to AD 1528, when Islam became dominant in the region.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Maritime Southeast Asia to 500 by Lynda Norene Shaffer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Öffentlichsarbeit & Verwaltung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 INTRODUCTION TO SOUTHEAST ASIA’S MARITIME REALM

DOI: 10.4324/9781315702551-1

An Asian El Dorado

In August of 1492, when Columbus set off from Spain on one of history’s most momentous journeys, he thought he was on his way to the original Spice Islands, islands within Southeast Asia’s maritime realm. Since Europe had no direct link by sea to the Indies (a term that referred to both the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia) or to China, he might have tried to repeat the 1487–88 feat of the Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias and sail around the tip of Africa in order to reach the Indian Ocean, but he was convinced that there was a better way. He thought he could find the islands by sailing westward across the unknown ocean that presumably stretched between western Europe and Asia.

When, in October 1492, Columbus had crossed this western ocean and sighted an island realm, he was sure that he had reached his destination, and until the day he died in 1506 he never admitted that the islands and coasts he had encountered on the opposite side of the Atlantic were not Asian. He called these islands the Indies, since that was what he was looking for, and the peoples who already lived in this other hemisphere have been called Indians ever since, a mistake that seems indelible. We now know that he did not find the much desired Spice Islands. Instead, his voyages revealed to Europeans two entirely new continents, lands previously unimagined by them. Ironically, however, Columbus remained frustrated and disappointed because he could not prove that all he had found was a new way to Asia.

Columbus was not interested in discovering a different hemisphere. What he wanted so desperately that he had risked sailing for months into an uncharted ocean was something quite different: to find an all-sea route from Europe to another part of the only hemisphere he knew, to a place that was well known, at least by reputation. He wanted to find the source of the fortune-making spices that were already prized in European markets.

Thus he was seeking islands that had been not only sought but found by long-distance traders for more than fifteen hundred years before Columbus embarked on his fateful journey, islands that in 1492 were already known to mariners all the way from East Africa to Okinawa. The first outsiders to set out in pursuit of the wealth of Southeast Asia’s maritime realm were Indians, from the Indian subcontinent, who arrived in the last centuries b.c.e. (Wheatley, 1973: 184). They had come seeking gold and were the first to name a part of the realm “The Land of Gold,” a name that later voyagers from the Middle East and China would also give to various locales on the peninsulas and islands of Southeast Asia.

By the first century c.e. this Asian El Dorado had proven to have much more than gold. Indian merchants were also interested in its pepper, eager to augment their own supplies so that they could meet the Roman demand. Although for several centuries thereafter the maritime realm’s most important exports would be aromatic woods and resins, gradually the traders of the Eastern Hemisphere discovered the even more profitable rare and “fine spices,” cloves, nutmeg, and mace. For more than a millennium before Columbus’s voyage, Asian and African sailors had supplied the ports of China, the Middle East, and East Africa with these spices, enriching Southeast Asia’s maritime realm as well as their own purses.

Given that so many people for so many centuries were seeking the markets of Southeast Asia’s maritime realm, it is surprising that its history before 1500 is not familiar to everyone interested in world history. But most of us in fact know little if anything about the people who created these extraordinarily magnetic spice markets, and thus we remain unaware of those who created the lure that drew so many of the world’s sailors out to distant seas, thereby to change the world, and themselves.

Definitions of the Region

Southeast Asia divides naturally into two parts, the mainland and the islands. Although many similarities, both cultural and geographic, link the two, there are some obvious differences. The mainland possesses long rivers (several flow all the way from the Tibetan highlands) that have formed large plains and deltas, whereas on the islands the rivers are short and fall steeply from mountain heights to ocean shores, a geographical difference that has been associated with certain cultural differences. In general, mainland societies have, for the most part, been preoccupied with their large and fertile plains, while the island peoples have tended to face out across the seas.

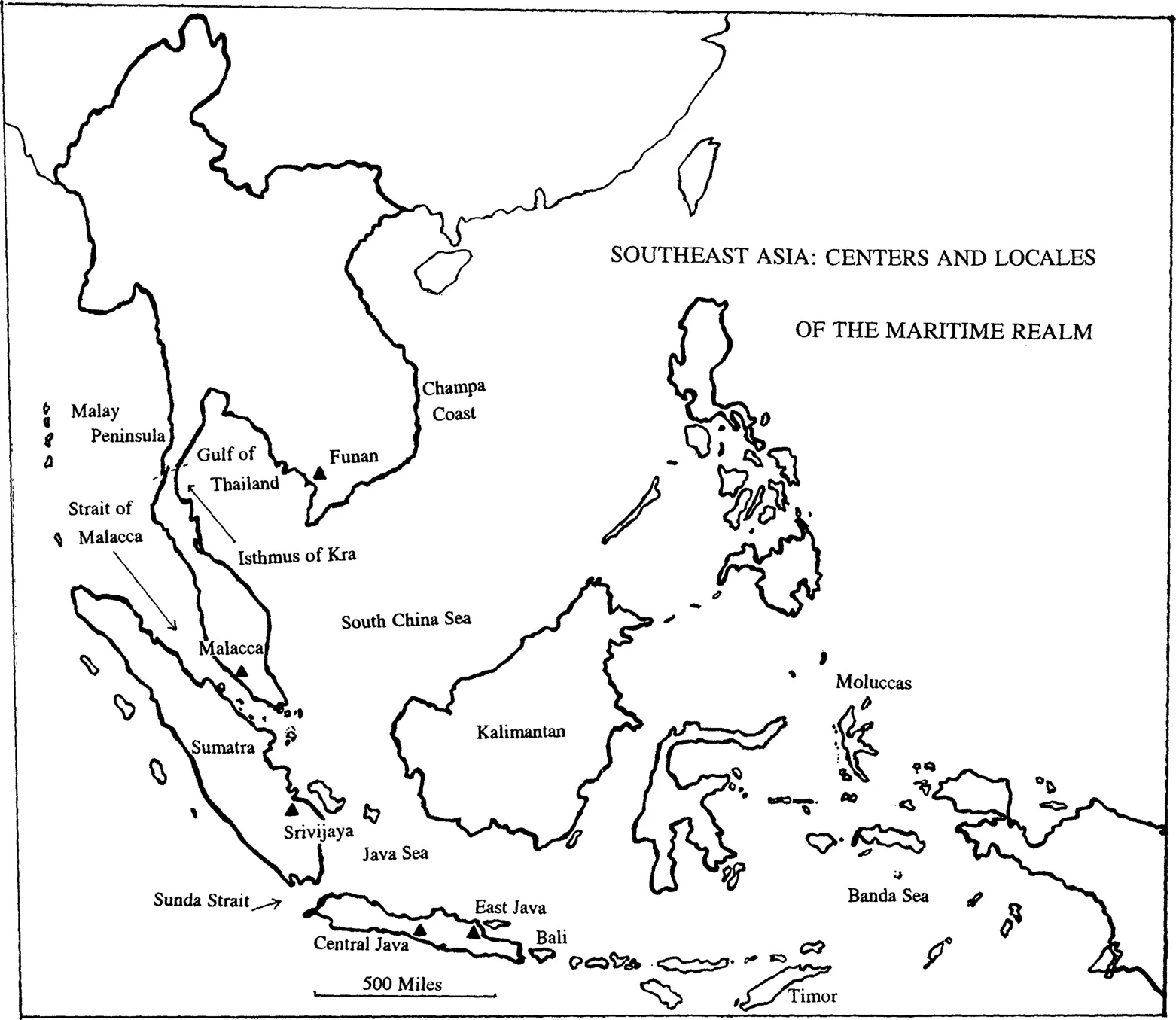

Such generalizations always pose problems, and this one is no exception. There are two places on the mainland that essentially belong to the island realm, at least in part because their landforms and topography resemble those of the islands. The southern part of the thousand-mile-long Malay Peninsula is essentially an island, almost separated from the mainland and almost surrounded by sea. Similarly, although less obviously, several hundred miles of the deeply indented and rugged coast of southeastern Vietnam provides a setting more like that of the islands than of the mainland. On the west a thick band of mountains separates this coast from the rest of Vietnam, and on the east thin lines of steep ridges run outward into the sea, creating many long and narrow “island-like enclaves defined by the sea and the mountains” (Taylor, 1992: 153). Thus Southeast Asia’s maritime realm, the seaward-looking realm, includes the southern part of the Malay Peninsula and the southeastern coast of Vietnam, as well as the islands.

In addition to the distinctiveness of its geography, Southeast Asia’s two parts are clearly marked by a linguistic divide. In the mainland countries of Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, and in most of Vietnam, people speak languages that belong to the Mon-Khmer, Thai-Kadai, or Sino-Tibetan families, whereas the peoples of the maritime realm (including the Cham peoples of Vietnam’s southeastern coast and the peoples of the southern portion of the Malay Peninsula) all speak closely related Malayo-Polynesian languages. (Singapore, with its large Chinese population, is today an exception to this rule, but prior to the nineteenth century few Chinese lived on its islands, and its people were Malayo-Polynesian speakers.)

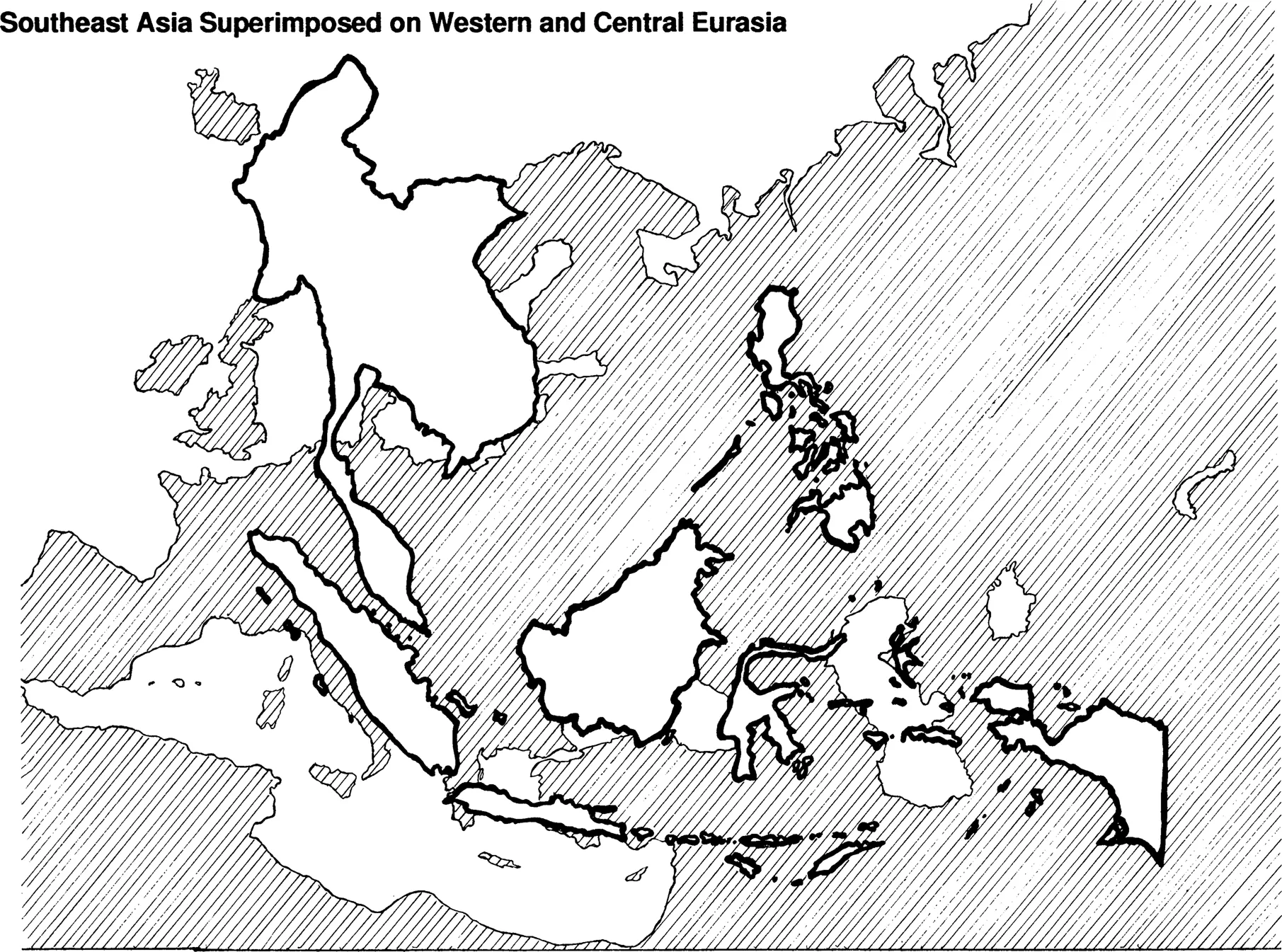

This maritime realm is quite large, much larger than most people realize. Defined according to modern boundaries, it includes the countries of Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines, as well as the southeastern coast of Vietnam. Indeed, were a map of the area superimposed upon one of Eurasia, with the realm’s western edge placed in France, its eastern edge would reach all the way to Afghanistan (see map, p. 6).

Three of these countries—the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore—are made up entirely of islands. The Philippines has 7,000 islands that follow a north-south axis for almost 1,000 miles, their land area totaling about 115,830 square miles. (The country’s land area is approximately the same as Italy’s, although the length of the island group is almost twice that of the Italian peninsula.) Only about one third of these islands have official names, and only about 7 percent are more than a single square mile in area.

Indonesia, the largest country in Southeast Asia, is made up of 13,667 islands, of which about 6,000 have names and about 1,000 have permanent residents. The land surfaceis approximately 735,000 square miles (an area almost as large as Mexico). From west to east (or east to west) the islands follow the equator for more than 3,000 miles, and if one were to draw a line around them all, the enclosed area (40 percent land and 60 percent water) would be almost 2 million square miles, or more than half the size of the United States (including Alaska).

Singapore, however, with its one main island and fifty-four others, has a total land area of only 238 square miles. Brunei, located on the island of Kalimantan, is ten times that size, with 2,226 square miles. The country of Malaysia includes the southern section of the Malay Peninsula, as well as Sarawak and Sabah, which are again located on the island of Kalimantan, across the South China Sea from the peninsula. Malaysia is thus part peninsula and part island, its total land area standing at approximately 128,300 square miles (which makes it somewhat larger than Norway).

Malay-Polynesian Origins

A scholarly consensus seems to have formed, although it does not go unquestioned, that the original homeland of the Malayo-Polynesian peoples was not in this maritime realm, with its immense stretches of sea and ocean punctuated by the steep mountain slopes of islands and peninsulas. Before 4000 b.c.e. these people lived in what is now southern China, in coastal areas south of the Yangzi River. This does not mean they were “Chinese” in the modern sense, since southern China at this point in time was culturally quite distinct from northern China. The peoples of the south consequently had relatively little connection with the ancestors of the Han Chinese who then lived further north, along the Yellow River and its tributaries. In contrast, though, southern China and mainland Southeast Asia were closely related, culturally, ethnically, and linguistically.

Some time around 4000 b.c.e. the ancestors of the Malayo-Polynesians left the mainland, by sea, and settled on the island of Taiwan. From Taiwan they subsequently moved south to the Philippines, and then to eastern Indonesia. Between 3000 and 2000 b.c.e. they went on to settle the islands and peninsulas of Southeast Asia’s maritime realm, and those who remained in this realm are now known as the Malays. By 1500 b.c.e. another group, those who would become the Polynesians, had migrated eastward as far as the Bismarck archipelago, northeast of New Guinea. Within a few centuries they could be found in what is now referred to as West Polynesia (Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa), where a distinctly Polynesian culture developed. Polynesian sailors continued eastward, eventually colonizing the most remote islands of Hawaii, Aotearoa (New Zealand), and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) (Finney, 1994: 277).

Rapa Nui, which was settled sometime around 500 c.e., is at least 1,500 miles from any other permanently inhabited island. Its settlers were living some 8,000 miles east of eastern Indonesia, whence their Malayo-Polynesian ancestors had come, and were thus only about 2,300 miles from the coast of South America (Finney, 1994: 284; Taylor, 1976: 38, 42, 52). Indeed, they may well have sailed all the way to South America. Long before any Europeans reached the Pacific Ocean, the Andean sweet potato was grown on some Polynesian islands (including what is now New Zealand) (Finney, 1994: 283), while manioc, another American domesticate, could be found on Easter Island and on other islands in eastern Polynesia. Although some have argued that the presence of American crops on various Pacific islands attests to Native American settlement in eastern Polynesia (Langdon, 1988: 330), the presence of these crops on some of the Polynesian islands could also be interpreted as evidence of contact between Polynesian sailors and South American coastal communities.

Early Southeast Asia

Long before the first outsiders began to seek out a Southeast Asian El Dorado in the last centuries b.c.e., the peoples of Southeast Asia, both on the mainland and in the maritime realm, were already accomplished farmers, metallurgists, and sailors. The ancestors of the Malayo-Polynesian peoples who lived along China’s southern coast were cultivating a domesticated variety of rice by 5000 b.c.e., a full millennium before the maritime migration of the Malayo-Polynesian peoples began. Archaeological sites in Zhejiang, south of the Yangzi River, had revealed that people lived in timber villages, manufactured wooden and bone agricultural tools, wove fibers, made clay pots, had woodworking tools, and kept domesticated dogs, pigs, and chickens. They also had boats, paddles, mats, and rope (Bellwood, 1992: 92), and some of these crops, crafts, and tools could have been carried along by the migrants who became the Malayo-Polynesians. It seems, however, that coconuts and breadfruit were first domesticated in the Philippines and then spread out from there (Bellwood, 1985: 216).

Yet another important cradle of early plant domestication was the highlands of New Guinea, at the eastern edge of Southeast Asia’s maritime region. The people who lived here were not Malayo-Polynesian but Papuan. They were one of the original peoples of Southeast Asia’s islands, descendants of Ice Age hunters and gatherers who populated many lands off the coast of Asia (including Australia and Tasmania) when glaciers had absorbed so much of the oceans’ waters that various land bridges were exposed. When people first came to New Guinea, about fifty thousand years ago, western Indonesia was on the Asian mainland, while New Guinea, Australia, and Tasmania were all part of the same landmass, now referred to by archaeologists as Sahul. Only narrow stretches of water, easily crossed by rafts, separated the mainland from New Guinea and the rest of Sahul (Finney, 1994: 274’76).

Although the dates have not yet been firmly established, Papuan agriculture in New Guinea may have begun as early as 8000 to 7000 b.c.e. (Finney, 1994: 291). Archaeological evidence suggests that many of the crops that became mainstays of the Malayo-Polynesian peoples who farmed within Southeast Asian rain forests were domesticated here. These would include a type of yam (Dioscorea), taro (Col-ocasia, also known as cocoyam), sago palm, and a certain variety of banana (Australimusa). The origins of sugarcane are still a matter of discussion. Some authorities associate this crop with southern China, while others believe that evidence indicates it was a domesticate of New Guinea (Bellwood, 1992: 91–94, 113).

Agricultural Productivity and Demographic Distribution

Because the maritime realm lies on or near the equator, neither the air temperature nor the length of the day varies noticeably as the planet makes its annual rotation around the sun. It does not experience the cold winters of the temperate zone, and except on the highest moun-taintops there is no such thing as frost. At sea level the temperature stays near 80° Fahrenheit all year round. Nor do hours of daylight shorten for half the year and lengthen for the other half, as they do in locations closer to the earth’s poles.

Even though a frost-free climate is ideal for farming, agricultural productivity in the maritime realm does vary according to soil type. On the mainland farming is most productive on large plains or deltas where long rivers deposit the topsoil of the mountains. In the maritime realm, however, because of its short and steep rivers, only small plains of river-deposited soil exist, and even those are few and far between. As a result, many farmers have to contend with the rain-forest soil of the mountains.

The mountains are indeed covered with tropical rain forests, bountiful providers of fruit, lumber, spice, and aromatic woods and resins. (They were also once home to an abundance of wild life, including tigers and elephants, as well as to bandits, who were oft...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Maps and Other Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Introduction to Southeast Asia’s Maritime Realm

- 2. In the Time of Funan

- 3. Srivijaya

- 4. Central Java

- 5. East Java

- 6. Singasari (1222 to 1292) and Majapahit (1292 to 1528)

- 7. The Establishment of Muslim Mataram

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author