This is a test

- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Short Literary History of the United States

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A Short Literary History of the United States offers an introduction to American Literature for students who want to acquaint themselves with the most important periods, authors, and works of American literary history. Comprehensive yet concise, it provides an essential overview of the different currents in American literature in an accessible, engaging style. This book features:

-

- the pre-colonial era to the present, including new media formats

- the evolution of literary traditions, themes, and aesthetics

- readings of individual texts, contextualized within American cultural history

- literary theory in the United States

- a core reading list in American Literature

- an extended glossary and study aid.

This book is ideal as a companion to courses in American Literature and American Studies, or as a study aid for exams.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Short Literary History of the United States by Mario Klarer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Discovery narratives

The most important cultural and historical impetus for the development of literature in and about America is, of course, the discovery of the New World in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. What seems obvious at first glance proves to be far more complex on closer inspection, since preconceived notions of America had existed in the European imagination long before the actual discovery of the new continent. Here, it is important to examine the background of Columbus’s discovery. The reason for his voyage was to find a new sea passage to India. Instead of going around the Cape of Good Hope eastward, Columbus embarked on a westward journey around the world. This route to the Far East via the West made it possible to fuse existing ideas concerning both hemispheres, the East and the West, into one composite image of America.

Greco-Roman and medieval texts had anchored the Far East of Asia and the extreme West of the Atlantic as utopian places in the European imagination. In the fourth century BC, for example, Plato described the fabled state of Atlantis as situated in the ocean beyond the Pillars of Hercules, the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. During the Middle Ages, fantastical travel reports, as, for example, by the Irish monk St. Brendan, continued these westward projections in descriptions of miraculous islands in the Atlantic. Parallel to an imaginary West, Judeo-Christian belief had located the earthly paradise in the East of Asia. In the Middle Ages, travel reports by Marco Polo and by the fantastical John Mandeville fueled and concretized this tradition of a paradisiacal Far East.

The moment that Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), and other explorers after him, set foot on the New World, they were confronted with an unknown and mostly unexplainable territory. The gaps in the knowledge about this terra incognita were eagerly filled with handed-down, utopian fantasies of the Far East and the West. Columbus’s first reports equated the New World with the Golden Age or the earthly paradise. Like the legendary land of milk and honey, it provides everything that is necessary for life. Food and mineral resources are plentiful, and a favorable climate enables several harvests a year. This paradise-like primordial condition resembles the Golden Age as imagined by the ancient poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses. The new continent was perceived as a “nourishing mother” – an “alma mater” – who selflessly and abundantly provides for her inhabitants.

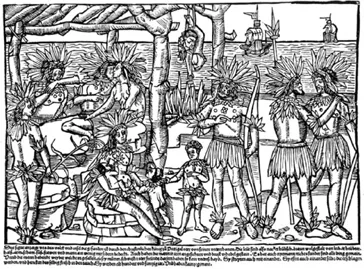

At first sight, the Natives of the New World seem to fit seamlessly into this harmonious exchange with Mother Nature. However, many of these early travel reports do not render the Natives as solely positive. In these accounts, the “noble savages” often paradoxically distinguish themselves through gruesome cannibalistic practices. Countless early travel reports of the New World, together with their pictorial illustrations, follow this ambivalent logic.

Figure 1.1 Woodcut from 1505, regarded as one of the earliest depictions of Native Americans.

Figure 1.2 “America,” engraving by Theodor Galle (1571–1633) after a drawing by Jan van der Straet (Stradanus, 1523–1604).

The oldest known visual representation of American Indians, a wood cut from the early sixteenth century, shows this bipolar dimension. On one level, this representation features a female Native in the pose of a “nourishing mother,” an image that must also be understood on an allegorical level. Like a mother who provides her child with everything it needs, the American continent will also provide in abundance for its inhabitants. Later allegories of America use similar visual strategies. An engraving from the early seventeenth century by Theodor Galle shows the discoverer Amerigo Vespucci next to a voluptuous female allegorization of America, idly reclining in a hammock and thus suggesting a land of plenty. In both visual portrayals, the depiction of America coincides with utopian, paradise-like fantasies.

However, upon closer examination, cannibals are lurking in the background, marring the idyllic nature of these visuals. In the woodcut with the depiction of American Indians, as well as in the later copper engraving with Amerigo Vespucci, we see inhabitants who either consume humans or are preparing humans for consumption.

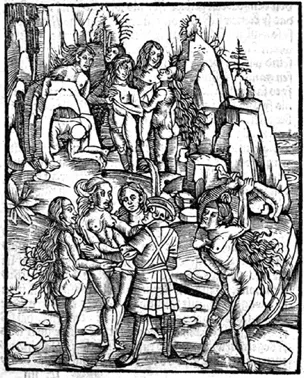

Exactly the same tension also governs the texts of early explorers, as, for example, Amerigo Vespucci’s (1452/54–1512) account of an incident during his third voyage in the early sixteenth century:

The young man advanced and mingled among the women; they all stood around him, and touched and stroked him, wondering greatly at him. At this point a woman came down from the hill carrying a big club. When she reached the place where the young man was standing, she struck him such a heavy blow from behind that he immediately fell to the ground dead. The rest of the women at once seized him and dragged him by the feet up the mountain. … There the women, who had killed the youth before our eyes, were now cutting him in pieces, showing us the pieces, roasting them at a large fire.

(138–139)

Figure 1.3 Woodcut depicting a scene from Amerigo Vespucci’s voyages from the 1509 Strasbourg edition of his Letter to Pier Soderini.

At first, a group of female Natives receives a young European sailor very positively, almost seductively, only to consequently kill, roast, and devour him before the eyes of the rest of the crew. Again, on the one hand, America is stylized as a benevolent female figure, guaranteeing abundance, but, on the other hand, she turns into a man-eating monster, lying in wait behind a caring façade.

The possibilities for explaining this paradox are many. It is obvious that these texts and visualizations operate with attraction and abjection as two seemingly opposing principles. We must not forget that these early texts and pictures mostly fulfilled an advertising function, inducing investors to finance further exploratory journeys and persuading potential settlers to enlist as colonists. In any case, the newly discovered land should be portrayed in the best way possible. What would work better than a utopian idealization of the land and its inhabitants? However, one could not portray the newly discovered territories as too perfect and ideal. After all, the colonial enterprise entailed – often under violent circumstances – the Europeans taking possession of the land. Cannibals were clearly better suited as the inevitable victims of colonial politics than strictly benevolent, noble savages of a Golden Age. The early picture of America therefore combines both traits: the utopian and the cannibalistic. Both dimensions mutually depend upon one another and make America prone to European colonial politics.

In the following centuries, the main elements of an earthly paradise as well as an uncontrollable wilderness remained connected with the different national identities in North and South America. Early knowledge of America in the European imagination in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries hardly distinguished between regions. Reports from Central America, South America, or territories of what later became the United States merged in the consciousness of the reader into one relatively undifferentiated picture of the New World. Thus, it is not surprising that this tension between paradise and wilderness has remained a leitmotif in the literature and the cultural history of the United States – even today.

Spaniards or seafarers traveling under the Spanish flag account for the earliest discoveries, as well as for forging a long-lasting image of the New World. The journeys of Columbus and Vespucci brought the Caribbean and South America to European awareness and inspired later conquistadors. With the conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519) in Mexico by Hernán Cortés, and the destruction of the Incan Empire in Peru (1533) by Francisco Pizarro, Spain forcibly secured its influence in Central and South America for centuries to come.

Spanish discoverers also visited the southern regions of the North American continent. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c.1490–c.1557) explored the area of today’s Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona on foot from 1528 to 1536. As the only survivors of a group of three hundred men after a shipwreck in Florida, de Vaca and three companions marched from the outlet of the Mississippi River to Mexico City. The group endured unbelievable strains and deprivations, including several years as slaves in the hands of Native tribes. After eight years of hardship and several thousand miles on foot, they finally reached the Spanish settlement in Mexico City. De Vaca’s report about his experiences was published in 1542 under the title La Relación and provides one of the earliest accounts of the southern territories of the United States. A few years after de Vaca, Hernando de Soto (1496 or 1500–1542) also explored the area of Florida and the Gulf Coast on a largescale expedition with over six hundred soldiers. Driven by the futile search for gold and treasures, de Soto’s four-year trip (1539–1542) was charac terized by brutal interactions with local tribes, often resulting in atrocious killings of Natives.

Roughly speaking, at the same time as de Soto’s venture into the Southeast, the Spanish crown commissioned a similar expedition to the Far West. Searching for the seven legendary golden cities of Cibola, Francisco Vásques de Coronado (1510–1554) set out in 1539 with an army of 350 soldiers, several hundred Natives, and a number of slaves. His journey led him from Mexico via Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma into the area of today’s Kansas. Splinter groups of his men even reached the Grand Canyon and came into contact with the pueblo tribes of the Hopi and Zuni. Needless to say, the search for the treasures of the legendary golden cities was not successful.

However, Spanish conquistadors and seafarers were not the only ones responsible for the discovery and exploration of the new continent. As early as 1497, only a few years after the first voyage of Columbus, the English king, Henry VII, sent the Italian John Cabot (c.1450–1498) on an exploratory journey into the Far North of America. Like Columbus half a decade before him, Cabot tried to reach Asia – this time by a supposedly shorter and more northern route. When he landed in Newfoundland, Labrador, and territories in New England, Cabot, like his predecessor, mistook them for China.

On a similar mission under French orders, the Italian Giovanni da Verrazano (1485–1528) in 1524 searched for a northwestern passage to Asia, thereby accidentally exploring the east coast of North America between Florida and Newfoundland. Sailing in the New York Bay as well as the lower reaches of the Hudson River, Verrazano believed he had found a passage to the Pacific. This misconception influenced cartography for a whole century, rendering America as a slim continent whose two landmasses form a narrow strait connecting the Atlantic with the Pacific.

The French continued to be instrumental in discovering and consequently colonizing the northern parts of the continent, including the territories of today’s Canada. In 1534 Jacques Cartier (1491–1557) explored Newfoundland, traveled the St. Lawrence River, and gave Montreal its name. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Samuel de Champlain (1567–1635) followed Cartier’s footsteps. In 1608 he founded the city of Quebec as the capital of the colony of New France and discovered, among others, Lake Huron and Lake Champlain in Vermont. Samuel de Champlain’s expeditions, taking him across the Atlantic over a dozen times, document in a unique way the life and customs of a number of Native tribes in North America. Champlain’s close cooperation with the Huron tribe inevitably involved him and his men in conflicts between the Huron and the Iroquois. The countless publications of his experiences and observations are some of the most significant documents of North American conditions before or at the beginning of European colonial endeavors. His reports not only provide deep insights into the regions of tod...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Introduction

- 1 Discovery narratives

- 2 Colonial literature

- 3 Literature of the Early Republic

- 4 Transcendentalism

- 5 American Renaissance

- 6 Gilded Age – Realism

- 7 Modernism

- 8 Postmodernism

- 9 Ethnic voices

- 10 Literary theory in the United States

- Extended glossary and study aid

- Suggested further reading

- Bibliography

- Author and title index

- Subject index