![]()

1

THE POSSESSIONS AT LOUDUN

Tracking the discourse of possession

Although it is, of necessity, finite, . . . historical knowledge is yet superior to all other human knowledge, since the comprehension by the actors of the parts that, in some sense, their own acting creates, will, if they understand the regular and recurrent structure of the ends and methods of social activity, be superior in kind to the knowledge possessed by spectators, however perceptive they may be. In history we are the actors; in the natural sciences mere spectators.

(Isaiah Berlin, Three Critics of the Enlightenment, p. 88)

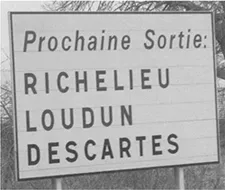

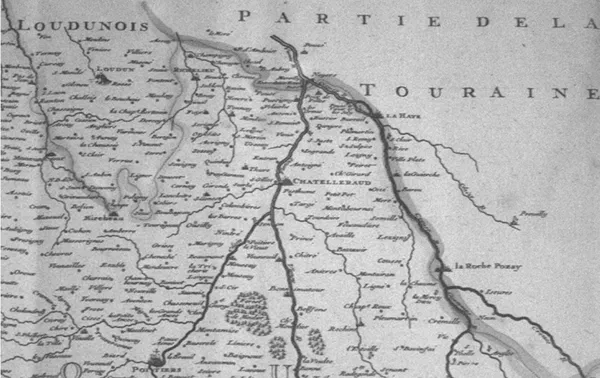

One of the best known cases of possession in Western European history took place in the French town of Loudun, some twenty kilometres west of Richelieu and sixty kilometres west of La Haye, the birthplace of Descartes. In 1631, Cardinal Richelieu received royal permission to construct the town that still bears his name as a monument to his own power. In 1633, in voluntary exile, Descartes suppressed publication of his treatise Le Monde after having learned of the trial of Galileo. From 1632 to 1638, Loudun was the unlikely epicentre of a collective crisis; it became the stage for a case of demonic possession that drew crowds from all over Europe. These three events are related by more than simple location and chronology. Taken together, they define a Zeitgeist and prefigured the direction in which Western philosophy and the science of mind would be carried.

Because the documentation of the Loudun possession is extremely copious, the lines of debate about possession as they shifted over four centuries can be tracked. This density of recorded events offers what Berlin especially privileges in the historical rather than the scientific: the opportunity to understand as actors rather than as spectators. Considering the case of Loudun necessarily means rationalizing and, perhaps, anachronistically psychologizing the data, but I hope to steer a course that will neither distance and dismiss the documented human suffering nor remystify a series of events that culminated in an appalling injustice and a collective act of great cruelty. Situating Jung’s concept of possession within this historical continuum shows how a Jungian perspective contributes a useful new approach to the debate.

Possession and the religious wars

After about 1520, Lutheranism began to gain a foothold in France, and by the 1550s, many had converted to the new religion from Catholicism, including a significant group of nobles. In 1562, the Edict of Saint-Germain granted the Protestant Huguenots some freedom of worship, but over the next thirty-six years it was withdrawn, restricted, or reinstated in no fewer than eight religious wars. Finally, in 1598, the Edict of Nantes granted permission for Protestants to worship as they chose. During these Wars of Religion, Catholic and Huguenot forces alternately pillaged and burned Loudun. The precarious equilibrium set by the Edict of Nantes allowed the town’s mostly Protestant population a period of consolidation, but in 1628, the fall of La Rochelle, a rebellious Huguenot port to the southwest, marked an ominous shift. Louis XIII made explicit his antipathy toward his subjects who had adopted the ‘so-called Reformed Religion’, and he began to demolish the outer walls and towers of towns to safeguard his kingdom from any opposition that might arise in Huguenot strongholds.

Loudun’s fate was both typical and exceptional. Typically, in 1617, its Protestant governor was replaced by a Catholic. Exceptionally, as a personal favour to the new governor and in contradiction to his command, Louis XIII granted the donjon, or great tower of Loudun, a reprieve from his wrecking crews; it still stands today. The people of Loudun responded to the fate of their donjon like secular citizens: for the most part, civic pride outweighed religion, with Catholics and Protestants alike rejoicing in the decision to safeguard the symbol of their city’s autonomy when neighbouring towns such as Mirebeau were losing theirs. This civil society did not last, however; the case of demonic possession that began in 1632 would drag the people back into irreconcilable fundamentalism.

The case of possession at Loudun did not appear out of the blue; in fact, four important cases can be seen as precedents. The first occurred in 1566 near Laon, in northern France. A sixteen-year-old girl, Nicole Obry, was said to be possessed by as many as thirty devils, primarily by one identified as Beelzebub. For two months, she was exorcised almost daily in front of large crowds on public stages constructed first within the church at Vervins and then at the cathedral of Laon. The principal tool employed by the exorcists was the Eucharist, a technique uncharacteristic of the contemporary procedures of exorcism defined in the Malleus Maleficarum (Sprenger and Kramer, 1486/1968); the exorcists apparently intended to convert the Huguenots, or at least confute them, by demonstrating the Real Presence in the consecrated Host. Certainly, the public dialogues between the exorcists and the demon Beelzebub residing within Nicole Obry vindicated several Catholic practices and beliefs that the Protestants attacked as superstitions: transubstantiation, the veneration of relics, the use of holy water, the signing of the cross and the power of names (Walker, 1981, p. 23).

The second precedent took place in 1582 at Soissons, also in northern France. Among the group of four possessed persons, the most notable was a fifty-year-old married man, Nicolas Facquier. His devil, named Cramoisy, claimed he was possessing Facquier to force three of his cousins, who were Huguenots, to convert to the true Church. Following the eventual and somewhat coerced conversion of all three, Facquier was successfully dispossessed. In this case, the propagandizing function of exorcism was explicit.

The third case involved propaganda even more clearly. In 1598, twenty-six-year-old Marthe Brossier, having apparently studied a book on the Miracle of Laon, travelled with her father to Paris just as the Paris Parliament was registering the Edict of Nantes, in which Henri IV granted all Huguenots freedom of worship. A year earlier, at Angers, a bishop had already tested Brossier’s symptoms of possession: by alternating holy water with ordinary water and words from his book of exorcisms with the first lines of the Aeneid, he had established that she was a fraud. Still, Brossier insisted that her possession was authentic, and during her public exorcisms in Paris, she ‘said marvellous things against the Huguenots’. Fearing that the fragile spirit of religious tolerance codified in the edict might be undermined with catastrophic results, the king ordered her detained, examined, and eventually escorted home and monitored by a resident judge. Dr. Michel Marescot’s report, published by royal command in 1599, argued that, in the opinion of the best physicians in France, nothing done by Brossier was preternatural; their diagnosis was ‘nihil a Spiritu, multa ficta, pauca a morbo’: ‘nothing from the Spirit, many things simulated, a few things from disease’ (Walker, 1981, p. 15). This report registered two significant official acknowledgements: that exorcism had become an important tool in the service of religious propaganda, and that physicians (and even bishops) had begun to identify fraud and naturally occurring sickness as possible causes for a demoniac’s behaviour.

The most important precedent to the events in Loudun occurred in 1611 at Aix-en-Provence. Here, for the first time, a connection was made between possession and witchcraft; though the demoniac was still perceived as suffering the traditional torments of the occupying demon, the demon was now deemed to be acting at the behest of a sorcerer. This shift from a dyad consisting of demoniacs and exorcists to a triad including a sorcerer is significant: legally, spiritually, psychologically, the demoniacs who gave voice to ‘evil spirits’ were freed from personal responsibility for their behaviour. They still had to undergo exorcism, but now the exorcists worked not only to expel the invading spiritual agent but also to identify and exterminate a guilty third party. In the case at Aix, based on evidence provided by Madeleine Demandolx and other nuns of her Ursuline order, a priest named Louis Gaufridy was convicted of sorcery and burned at the stake.

Polarization in Loudun

According to ecclesiastical records, the events at Loudun began on 22 September 1632, when Jeanne des Anges, the prioress of the Ursuline convent, Sister de Colombiers, the sub-prioress, and Sister Marthe de Saint-Monique, a junior nun, were each visited separately during the same night by an apparition of ‘a man of the cloth’ asking for help. On the evening of 24 September, in the refectory, another spectre in the form of a black sphere knocked Sister Marthe to the ground and Jeanne des Anges into a chair. Strange disturbances continued: the nuns heard mysterious voices, experienced physical blows from unseen sources, and found themselves gripped by fits of uncontrollable laughter. Finally, physical evidence of possession appeared: three hawthorns were seemingly passed from a ghostly hand into the palm of the prioress. After this, most of the nuns were stricken with bouts of uncontrollable convulsions and irrational behaviour. The first exorcisms were conducted on 5 October 1632, and many more followed, eventually expanding into huge public events which attracted thousands of curious onlookers from all over Europe. On 18 August 1634, Urbain Grandier, parish priest of Saint-Pierre-du-Marché in Loudun, was found guilty of the crimes of sorcery and casting evil spells; above all, he was declared responsible for the possession visited upon the Ursulines. He was burned at the stake the same day. Even though the sorcerer had been executed, the exorcisms continued, though no longer as public spectacles, until 1638.

The hundreds of books and essays about the possession at Loudun and the trial and execution of Urbain Grandier show how abruptly the brief period of tolerance and civic cooperation between Catholics and Protestants ended. The first account, Veritable relation des justes procedures observees au fait de la possession des Ursulines de Loudun, et an proces de Grandier, by Reverend Father Tranquille (1634), a member of one of the earliest teams of exorcists, is a polemic on behalf of the exorcists and the rites of the Church. Tranquille’s rhetoric demonstrates his purpose: to defend his own actions and to condemn the considerable public scepticism about the nuns’ possession and disapproval of Grandier’s judges. Tranquille’s argument emphasized that a possession is either genuinely demonic or it is voluntary and wilful. But Tranquille did not acknowledge the skewed political situation in the town. The dissenting audience to whom he addressed his arguments had no voice during Grandier’s trial. A court order announced from the pulpits of Loudun and posted in public places forbade debate or disagreement about the possessions or the legal proceedings, on pain of death.

As early as 1637, in ‘Relation de M. Hédelin, abbé d’Aubignac, touchant les possédées de Loudun’, a visitor to Loudun voiced scepticism about what he witnessed (Hédelin, 1637). It could be argued that the possessions at Loudun unfolded like a textbook case, that details right down to the hawthorns in the prioress’s hand occurred in accordance with books such as Histoire admirable de la possession et conversion d’une penitente, which the exorcist Father Sébastien Michaëlis of Aix-en-Provence had written in 1613. Indeed, just a week after the first exorcisms on 5 October 1632, Father Mignon, the nuns’ confessor, was already citing the case of Aix and the possessed Ursulines, with its unprecedented outcome, the execution of a priest as a sorcerer. Although d’Aubignac was a Catholic witness, he remained unconvinced that the criteria for possession had been adequately established, nor did the manner in which the exorcisms were performed please him.

Grandier’s trial had legitimized the evidence of the demoniacs and the exorcists, and the court order rendered all objections illegal. As a result, the opposing Protestant position was not available in print, and in 1685, the Edict of Nantes, which had granted the Huguenots a grudging tolerance, was revoked. Not until 1693 did Nicolas Aubin, a Huguenot from Loudun who had lived in exile in Amsterdam for seven years, publish his Histoire des diables de Loudun. Aubin argued that the Huguenots of Loudun had been maliciously undermined by ‘the long and deadly intrigues of a convent of nuns and a great number of ecclesiastics, supported by a body of magistrates, of habitants of the town, and favourites of the court’. Aubin even identified a culprit at the centre of the affair: Father Mignon, the nuns’ confessor at the time of the first events. Aubin dramatized Father Mignon’s instructions to the nuns about how best to perform during the public exorcisms so they would both incriminate Grandier, who was reputedly a libertine and an embarrassment to the Catholic cause, and, more importantly, demonstrate the power of Catholic ritual over the devil and thereby undermine the all-too-powerful Huguenot position in Loudun. Circumstantial evidence to support Aubin’s argument is not difficult to find: following the execution of Grandier, the court confiscated what had been, until that moment, a reputable Huguenot college and rehoused the Ursulines there, to their great advantage.

The language of possession

The language of possession has been fluid during the history of European religion, and the ‘set texts’ on which d’Aubignac relied for a clear statement of diagnostic criteria were orthodox only to his particular time and place.

In early medieval medical terminology, ‘possession’ probably referred more to the intermittency of manic attacks than to any notion of causation (Demaitre, 1982). Differences in emphasis can be attributed to different conceptions of ‘devil’, a word that, in the medieval imagination, synthesized to varying degrees the biblical Satan, the mythic fallen angels, and the daimones of Hellenistic paganism (Pagels, 1995; Boureau, 2004). In the early Middle Ages, the devil’s field of action was the imagination, not the body or corporeal reality. Between the third and fifth centuries, Tertullian, Augustine, and John Cassion portrayed the devil as, most importantly, a deceiver who employs fantasmata to lead the soul astray, and one falls prey to the devil particularly in dreams. True dreams come from God; the devil fills dreams with false and tempting images. The Canon Episcopi (916) described ‘certain wicked women, instruments of Satan who were themselves deceived by diabolical apparitions’, believing that they rode by night on herds of animals following the sorceress Holda (or, as William of Auvergne, Bishop of Paris, more tolerantly called her, Abundia or Satia). The Church denounced these alleged nocturnal voyages associated with pagan fertility rites. It argued that the participants mistakenly believed that these phantasms actually occurred in time and space rather than in their imaginations, and it took upon itself the duty to heal people whose sick imaginations were leading them away from God.

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, however, the church reversed this position and attributed corporeal reality to the devil’s fantasmata (Schmitt, 1982). The pontifical constitution Vox in Rama (1233) described paying homage to Satan as a feudal osculum in reverse – kissing the devil’s anus – and it rendered nocturnal dream voyages into quasi-religious meetings marked by physical (not imaginary) acts of incest, sodomy, infanticide and cannibalism. Jean Vineti, a theologian and inquisitor, circumvented the argument in the Canon Episcopi that witches’ sabbaths were only diabolical illusions and sorcerers deceived souls; in his Tractatus contra daemonum invocatores, he identified devil worship as a new phenomenon, distinct from traditional rustic sorcery. Jacobus Sprenger and Heinrich Kramer, two inquisitors of the Rhineland, specified in their Malleus Maleficarum (1486/1968) that this chan...