![]()

1

THE DYNAMICS OF RECOVERY

Two examples

Experts talk of ‘building back better’, of concepts like ‘resilience’ and ‘sustainability’, of crisis being opportunity in the way that it was for the devastated cities of Germany and Japan in 1945.

The practice … can be very different; piecemeal, dilatory, bureaucratic, venal even. Urban planners, it seems, never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity. But occasionally, just occasionally, they surprise on the upside too, and reimagine the city in ways that might have been impossible had disaster not struck.

(Rice-Oxley 2014)

Examples of positive and negative recovery

A rich collection of metaphors is used to describe the complicated process of disaster recovery: melting pots, moving targets, spiders’ webs, roots and branches, jigsaw puzzles, and so on. Writers have used these pictures as they attempt to capture the right image of a recovery operation that involves people, institutions, structures, issues, policies, plans, pressures, progress or stagnation, and hopes. We consider varied models of recovery in Chapters 3 and 4 (see Appendix 1 for a summary of models), but we have found that these complex realities and relationships are best conveyed in the narrative of observed experience. Therefore we launch straight into our book with a pair of contrasting examples of disaster recovery after earthquakes in India and Sicily.

One of these was highly successful while the other was less successful and gave rise to some opportunities that were missed. We selected them because we have first-hand experience of both situations over different stages of the recovery process; and we make no apology for including the broad ‘macroscopic’ elements in each story as well some of the minor details conveyed in our drawings and photographs, for the ‘magic is in the details’. These examples relate to the first and second models (the ‘progress with recovery’ model and the ‘recovery sectors’ model) that appear at the beginning of Chapter 3.

Successful recovery of Malkondji village following the 1993 Latur earthquake in Maharashtra State, India1

In a remote rural town, Latur, and surrounding villages in the Indian state of Maharashtra, a magnitude 6.4 earthquake occurred at 3.30 in the morning on 30 September 1993 while people were sleeping in heavy masonry dwellings. In a manner typical of earthquakes that occur at night, casualties were high. It is estimated that 7,928 people were killed and 16,000 were injured. Some 37 villages were catastrophically damaged and about 30,000 houses collapsed. The earthquake did not occur in one of the well-known seismic zones of India; this lack of history of recent disasters partly explains the absence of building codes designed to guarantee seismic resistance in Latur, as well as the consequent high levels of damage to dwellings (Figure 1.1).

The Government of Maharashtra managed the earthquake recovery process with considerable skill, setting standards of cost and space for dwellings and specifying the minimum earthquake resistance of reconstructed buildings. They then assigned the reconstruction of various villages to those agencies that were able to produce evidence that they had adequate resources and experience to complete the job well. One village, Malkondji, had a population of 1,562 distributed among 281 households; in the earthquake, seven people lost their lives and five were injured. The village was made up of houses constructed with unreinforced stone masonry walls, locally called malwad, with heavy wooden roofs covered with a thick layer of mud – a form of construction that is highly vulnerable to seismic damage. The reconstruction of this agrarian village was entrusted to a Christian NGO called the Evangelical Fellowship of India Commission of Relief (EFICOR). This decision was taken despite the fact that disaster reconstruction was not EFICOR’s normal area of expertise – its particular strength lay in community-based projects. Meanwhile, the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID) had £750,000 (about US$1.5 million) to spend on reconstruction and decided to allocate it to a single community rather than to disperse it more widely. In recognition of its accountability to British taxpayers, DFID also decided to work through Tearfund – a British NGO which had built a good working partnership with EFICOR.

FIGURE 1.1 Earthquake damage to stone masonry dwellings in Malkondji (sketch by Ian Davis).

At that time, Ian Davis was leading a disaster management consultancy organisation, and one of the organisation’s staff was sent out to India by Tearfund in 1994 to discuss how to begin the design of the village. We supported the idea that the design should adopt a cluster approach that had been proposed by renowned British architect Laurie Baker, who had worked in South India from 1945 until his death in 2007 (Bhatia 1991):

I learn my architecture by watching what ordinary people do; in any case, it’s always the cheapest and the simplest. They didn’t even employ builders but the families did it themselves.

[M]y feeling as an architect is that you’re not after all trying to put up a monument which will be remembered as ‘a Laurie Baker Building’ but Mohan Singh’s house where he can live happily with his family.

(Bhatia 1986: 218)

Baker’s ‘architecture as service’ approach was radically different from the way most architects were operating, and his architectural layout was a refreshing alternative to the monotonous rows of regimented ‘barrack-style’ dwellings that were the default design used by the Government of India and most agencies. Tearfund also encouraged the appointment of a progressive Indian firm of consultants called Development Alternatives to provide the detailed design and technical services. Baker’s planning approach included the allocation of communal spaces, public buildings and extensive tree planting to provide shade, fruit and medicine. An important aspect was to retain a traditional feature in villages in the region by building compound walls to surround properties so as to provide privacy as well as protection for livestock that were brought in from the fields every night to avoid risk of theft (Figure 1.2).

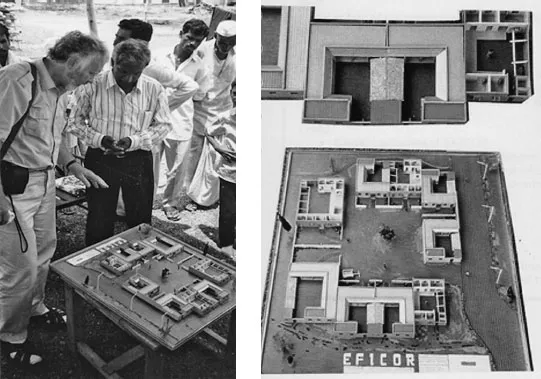

FIGURE 1.2 Model of housing cluster layout. In 1996, the site engineer, Mr Mandappa, is explaining the cluster layout to Ian. After many failed attempts to explain the house and cluster layout to the residents using architects plans, a model was prepared, and immediately everyone understood the design concept (photographs by Ian Davis).

The settlement was located about 600 metres from the destroyed village (illustrated in Figure 1.1). A strong participatory process in decision-making was characteristic of EFICOR’s approach, and the agency and their planning consultants decided to build 336 identical houses, each being 34.5 square meters, using a ‘core house’ principle, carefully planned with sufficient space for later expansion. Houses were constructed in cement blocks, strengthened with ring beams made of reinforced concrete that were positioned at plinth and lintel levels. The roofs were constructed in reinforced concrete. The layout was for a single-family unit and was composed of two rooms, one for use as a kitchen and the other room for sleeping. A separate unit was provided with a bathroom and pit latrine.

In 1996 as the reconstruction project was nearing completion, Ian was asked to lead an evaluation team to assess the recovery of the village, including the reconstruction of houses. The evaluation included examination of the following sectors: health, community development, engineering and planning. It benefitted from the expertise of Mihir Bhatt, the founder and leader of the All India Disaster Mitigation Institute (AIDMI) (Davis and Bhatt 1996)

The results of the evaluation were generally positive, indicating a good level of involvement of the community in the design of the settlement and the dwellings (Figure 1.2). The sensible cluster layout enabled farming families to bring their cattle into communal courtyards at night to provide protection against animal theft. The team also recognised the value of training masons to build safe, robust houses. It was, however, divided over the wisdom of the decision to incorporate toilets in each dwelling as only a small fraction were being used for their intended purpose, most of the others being used for grain storage. Some of the team believed that it would take a generation for these rural communities to become accustomed to toilets instead of their traditional practice of going to the fields.

FIGURE 1.3 Completed houses in the main street of Malkondji. An avenue of trees has been planted by the side of the road (photograph by Ian Davis).

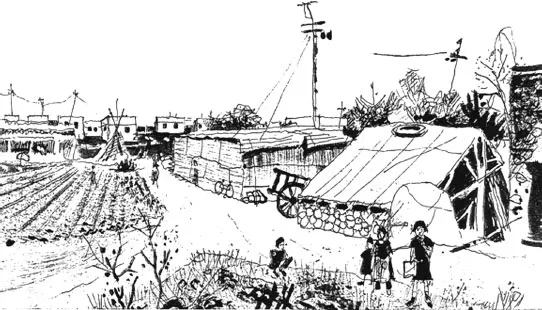

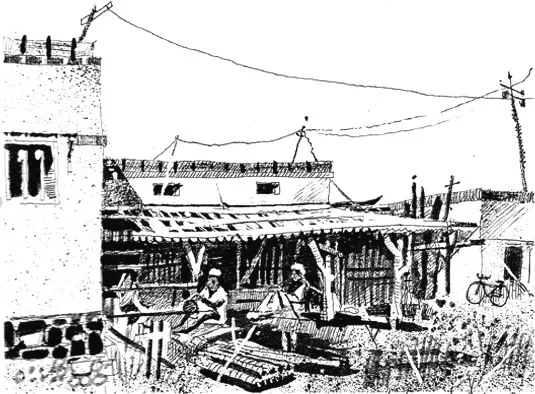

FIGURE 1.4 Sketch of Malkondji in 1996, three years after the earthquake. In the foreground, there are varied forms of improvised shelters that were built by survivors. Others have been replaced with the permanent new dwellings that appear in the background (sketch by Ian Davis).

In the disaster recovery field, long-term ‘longitudinal’ evaluations are exceedingly rare, but, as Ian remembers: in January 2011, our curiosity about progress in Malkondji during the intervening 15 years led us to return to the village. We asked three members of the original evaluation team to revisit the village in order to gauge long-term progress. The team included Mihir Bhatt, with his AIDMI colleagues, and the Director of EFICOR’s Reconstruction Programme, Thomas Swaroop, together with his colleagues. None of the team had visited the village since 1996.

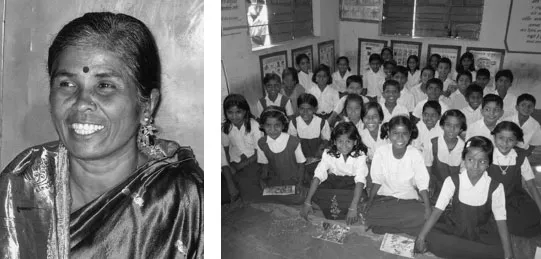

We were warmly welcomed back and the results were beyond our expectations in virtually all areas. Social progress had been significant. The most unexpected result was that 98 per cent of all dwellings had toilets in use following action by the headmistress of the local school, who insisted that on health grounds all children used the school toilets and also those at home. The parents and other family members were therefore ‘educated’ by their own children who, in current development jargon, became the ‘agents of change’. This reminds one of the social reformers in nineteenth-century Britain who argued that working-class people should have running water and baths in their homes, at which the critique was levelled that the baths would be used to store coal. Of course, that was not the case.

Generally, social organisation in Malkondji was excellent. Various public buildings and facilities had been added since our 1996 evaluation: the school, a health centre, a temple and a sports ground. Local leaders took great pride when, in 2008, Malkondji was awarded a prize for being the best village in Maharashtra.

We reviewed progress in the provision of dwellings and established that the distribution of houses had been equitable and had taken place according to family needs. The cluster layouts of houses were working well, with full use of courtyards for the protection of cattle as envisaged by the architect. The compound walls that enclosed individual dwellings were greatly appreciated by residents (Figure 1.2). Throughout the town, dwellings had been enlarged – in a few cases, with the addition of a second storey.

FIGURE 1.5 Headmistress of Malkondji School and a class of schoolgirls. Together they were the ‘change agents’ of Malkondji School in 2011 who introduced the use of toilets into the village (photographs by Ian Davis).

FIGURE 1.6 Many house occupants added covered spaces to their dwellings for various household and occupational tasks (sketch by Ian Davis).

Support from the World Bank had enabled the infrastructure to be improved, including the arrival of electricity and piped water as well as surfaced roads that allowed a bus route to be added. Trees that had been planted beside roads by the Indian Department of Forestry were now fully grown and provided excellent shade. The medicinal Neem trees, wisely planted in each reconstructed village, were greatly valued by villagers.

The village economy was in good shape, with some useful diversification of employment beyond farming. We discovered that the original training course in safe building construction had enabled some local farm labourers to secure occasional building work and thus diversify their sources of income.

A minor regret experienced by our team was the decision the village had taken to demolish historic buildings possessing rather beautiful masonry and carved timber that had been ruined in the disaster. Their retention, in their ruined form, could have provided a valuable link with the past; but for the residents, these ruins were merely a painful memory of the disaster they had suffered and were therefore not to be retained. It was also clear that more public education was needed regarding community preparedness against future earthquake disasters and other hazard threats.

As we left Malkondji after its second assessment, members pondered on the possible reasons why this community had recovered successfully. One underlying factor may be that only seven villagers died in the earthquake. In contrast to other villages where there was a high toll of death and injury, this may be a significant influence upon the psychosocial recovery of the community. Where family losses were extensive, it was always likely that recovery would be incomplete.

We concluded that a decisive factor had been the culturally and environmentally sensitive design of the settlement and its dwellings. Qualities that contributed to success included the clustering of buildings instead of grouping them in tedious rows, the space allotted to expansion, streets that are curved rather than straight, extensive planting of trees, ample provision of community buildings and vital new infrastructure. We noted that there had been a high level of participation by the beneficiaries from the outset of the project, in both formal and informal ways. This occurred in the design and allocation of dwellings, the management of projects and the construction of dwellings. All of these were vital components of success.

A persistent theme throughout this book is that process is often more important than product, and indeed the manner in which the village had been reconstructed seems to have been particularly important. When building work began, EFICOR and Development Alternatives set up basic camp-style living accommod...