![]()

1

The workforce and the labour market

Heather McLaughlin and Colm Fearon

Introduction

Seafaring dates back many centuries, derived from the growth of international seaborne trade. Modern seafaring is truly a profession, demanding high levels of internationally regulated skills and competencies and carrying considerable risk and responsibility. Once an exciting and adventurous proposition, competing shore-based job opportunities have lessened the attraction of a seafaring career and we are now witnessing a global imbalance of demand and supply, particularly at officer level. It is generally recognised that recruitment and retention issues need to be addressed on an international scale. In order to do this, we need to understand the unique characteristics of this labour market. This chapter examines the workforce from an economics perspective, by considering the factors that influence demand and supply as well as the various market imperfections which can lead to discriminatory practices. International institutions play a significant role in addressing some of these issues and ensuring that the market is appropriately regulated. Finally there is a discussion of the importance of maintaining seafaring skills for relevant shore-based careers in the wider maritime cluster.

A historical perspective

Waterborne transport can be traced back thousands of years. Indeed, in the pre-road era, it was far easier to move goods by water than on the footpaths that linked town and villages. Major waterways such as the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates, and Yellow River became vital to the development of early civilisations. As vessels became more robust, the Eastern Mediterranean was the first region to develop significant maritime trade, notably by the Phoenicians who traded luxury goods such as wood and ivory carvings as well as an expensive dye called Tyrian purple through the Mediterranean islands and along the African coast (circa 945 BC).

Trading expanded through the ages with the development of new technologies and new routes, but it was the so-called ‘Age of Discovery’ (15th to 18th century) that saw significant changes, fuelled by the search for new trading routes and partners to satisfy the appetite of an increasingly wealthy European population. During this time, many explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Vasco da Gama, and John Cabot travelled significant distances in search of alternative trade routes to the West and East Indies and the Americas. Towards the end of this period, the clipper route between Europe and the Far East, Australia, and New Zealand became well established. Sailing conditions were particularly difficult especially around Cape Horn where many ships and sailors were lost. Cutty Sark was one of the most famous of the clipper ships and one of the fastest, capable of a maximum speed of 17.5 knots (Lubbock, 1924). Built in 1869, she was also one of the last sailing ships of that age which gave way to the more reliable steam ship in the late 19th century. Further developments in the 20th century saw the internal combustion engine and gas turbine replace the steam engine in most ship applications. Now in the 21st century, modern vessels are amongst the largest and most complex mobile structures known to man, and are at the forefront of new technology and design.

But what of the seafarer? There is no doubt that seafaring from the time of the early explorers through the age of the sail was a very hazardous profession. Quite apart from the dangers of the sea and the other elements, life on board was filled with hardship. Sailors lived in very cramped conditions, were exposed to a range of diseases, and endured a poor diet and low pay. Voyages were long and they were cut off from normal life ashore for months at a time (Royal Museums Greenwich, 2015).

With the advancements in technology, seafaring in the mid-20th century became a career with good pay, benefits, fast advancement, and an opportunity to see the world. However, the advent of air travel coupled with much faster turnaround times in port removed the attraction for those seeking a global adventure. As Goss (1995) remarked:

the very changes which have raised seamen’s productivity have reduced the quality of their lives. A seafarer no longer has time to enjoy foreign ports, since his ship’s stay is brief and he has much work to do in port. Increasingly, his ship’s berth is likely, as with tanker terminals, to be far from the nearest town. (p.279)

Equally, economic prosperity in the traditional maritime nations increased the number of appealing shore-based opportunities offering competitive pay and a better work–life balance. Shipowners operating on tight margins were unable to compete on salary and so looked towards alternative and cheaper sources of labour. So we have seen a decline in the number of seafarers from ‘traditional’ maritime nations, and the development of a new concept of ‘seafaring labour supplying countries’, many of which have no obvious maritime tradition.

The seafaring labour market

In basic economic terms, labour is a primary factor of production. It refers to human physical effort, skill, or intellectual power deployed in productive service. As a branch of economics, labour is subject to similar analysis as that of other factors of production but also faces some distinct challenges and characteristics.

The function of any market is to bring buyers and sellers together. Neo-classical economists view the labour market as similar to others in that the interaction of supply and demand determines the price (wage rate) and quantity (numbers of people employed). However, unlike many other markets such as the market for goods, supply cannot be ‘manufactured’ as people have limited amounts of time in the day. The labour market may also be non-clearing in that it may experience persistent unemployment. Finally, it is subject to a number of imperfections that create differentials between workers. This is particularly true of the seafaring labour market which operates across national boundaries but is segregated by legislation and culture. In addition, it is strongly influenced by national and international institutions which are absent in other factor markets. As Leggate and McConville (2002a) observed:

The seafarer is the archetypal international worker, employed on board vessels registered under different flags, owned and operated by citizens of many countries … Such a geographically diverse industry is dependent on international regulation to establish and ensure adherence to acceptable standards and conditions of employment. (p.449)

The following section examines the factors which determine demand for and supply of seafaring labour and the challenges faced in terms of recruitment and retention.

Demand and supply

It is perhaps surprising to discover that we had no idea of the global supply of and demand for seafarers until 1990, when the Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) and the International Shipping Federation (ISF) launched their first ground-breaking report. This BIMCO/ISF Manpower Study was the first to estimate these figures and highlight that there was an excess of ratings but a shortage of seafaring officers to man the global fleet, and has since been repeated and refined every five years. The findings received little challenge until 2004 when other studies emerged to question the numbers (Drewry Shipping Consultants, 2008; Japan International Transport Institute and The Nippon Foundation, 2010; Leggate, 2004) as well as the more specific skills shortages (Nguyen et al., 2014). However, the overall message of officer shortage has remained the same.

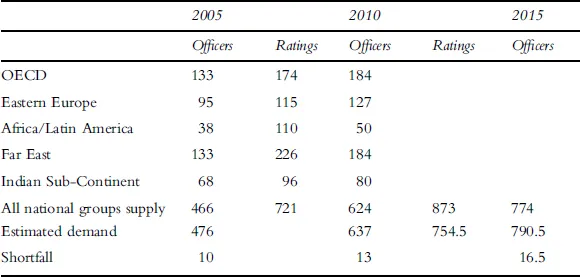

In order to provide shipping services, shipowners or operators use a combination of capital, labour, and technology. The price of this service is determined by the interaction of supply of and demand for the service on the open market and is expressed as a freight rate. Shipping services are not demanded of themselves, but are derived from the demand by the consumers for the commodities being shipped. It follows therefore, that the demand for seafaring labour is dependent on the demand for those maritime services. In recent years, the global demand for seafarers has been estimated by BIMCO/ISF Manpower Survey based on fleet size and manning scales, and calibrated by survey data from 100 major companies as well as information from national maritime administrations and crewing experts. According to latest BIMCO/ISF estimates, the worldwide demand for seafarers in 2015 was 790,500 officers and 754,000 ratings (see Table 1.1).

In any labour market, the total supply of labour is dependent on individual decisions of those who are eligible to seek employment. Such decisions will be influenced by age, family commitments, and other available opportunities. However, in most cases workers have little or no choice about entering the market because of an economic imperative to earn money. In the seafaring context, the decision is complicated by a need to meet eligibility criteria in the form of skills, education, training, and experience.

The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) 1978, as amended in 1995 and again in 2010, sets those standards, governs the award of certificates and controls watchkeeping arrangements. The Convention was adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 1978 and came into force in 1984. During the late 1980s, it was clear that STCW-78 was not achieving its aim of raising professional standards worldwide, and so IMO members decided to amend it. This was done in the early 1990s, and the amended convention was then called STCW-95. In June 2010, a diplomatic conference in Manila adopted a comprehensive set of amendments to the original Convention that came into force in January 2012 which recognised the particular training issues for the modern-day seafarer. Important changes were made to the monitoring of certificates in the wake of fraudulent practices, the need for training in modern technologies, awareness of marine environment, and security issues. There was also an introduction of modern training methodology including distance and web-based learning, as well as an overall commitment to harmonise the amended STCW Convention, where practical, with the provisions of the 2006 ILO Maritime Labour Convention. The standard set by the Convention applies to seafarers of all ranks serving on sea-going vessels.

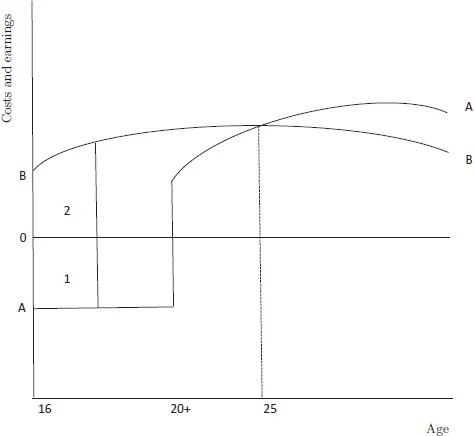

Hence seafaring labour is not simply about numbers but quality. Competencies are required by the individual which facilitate the earning of income. These competencies are obtained largely through education and training to achieve professional qualifications. In terms of the theory of investment in human capital, seafarers will make individual decisions about foregoing initial earnings and bearing the costs of education and training in expectation of future higher earnings. Indeed, it is possible to examine the differences between ratings and officers in this way, where ratings are essentially learning on the job and officers continue in full-time education in order to gain the necessary qualifications that enable them to secure higher salaries after the training period.

Figure 1.1 illustrates this proposition, with costs and earnings measured on the Y axis and age on the X axis. The potential working life of a rating begins at the age of 16 on completion of school education which normally has zero cost to the seafarer. At this point the seafarer is unskilled but receives some form of induction and then on-the-job training, gathering experience which causes earnings to rise modestly with age up to the point where (s)he may decide to spend more time at leisure which causes earnings to fall. This is shown by curve BB. At 16, an aspiring officer will invest in the costs of further education for several years before entering the work force (see area 1). Occasionally, this will be subsidised by the shipping company or even government, but this is not usually the norm. In addition, the officer will be subject to another cost, namely the opportunity cost of not earning during this period (see area 2). However, by the age of about 25, the officer’s income will exceed that of the rating and the upward trend continues (see AA).

Figure 1.1 Investment in education and training

Such investment in education and training was traditionally made by the aspiring officers from the developed nations, but this has changed significantly over recent years with the world fleet operated largely by seafarers from developing countries, the so-called ‘labour supplying countries’ notably the Philippines, India, and Eastern Europe. Even with this increasing trend, there is a global shortage of officers. Table 1.1 shows the trends in seafarer numbers over the last ten years together with the demand estimates.

Table 1.1 Trends in global seafarer numbers (’000s)

Sources: BIMCO/ISF, 2005, 2010, 2015.

The figures show the persistent shortfall in the number of officers required to service the world fleet, and the changes in the nationality mix. Over recent decades, there has been a proportionate decline in the number of seafarers coming from developed countries, due to an appreciable reduction in recruitment and retention. In contrast, the proportion of officers and ratings from developing countries has increased.

BIMCO/ISF (2015) notes that shortages are more acute in certain specialised sectors such as tankers and offshore support vessels. The company surveys also indicate issues of supply of senior officers and engineers in some markets. The Manning Report (Drewry Shipping Consultants, 2015) confirms this trend, suggesting that the industry will require an additional 42,500 officers by 2019. Although there is evidence that this persistent shortage of officer crew is lessening, the deficit still raises the longer-term question of how the industry attracts and retains talented crews.

Recruitment and retention

So how is the industry addressing this issue of recruitment and retention? Research such as Kokoszko and Cahoon (2007) and Wilkinson and Cahoon (2008) have recommended greater attention to the marketing efforts of individual shipping companies and the shipping industry as a whole, as a means of drawing positive attention to the benefits of working in the shipping industry sector. They urge individual shipping companies to re-examine their human resources practices and introduce best practice strategies to become recognised as employers of choice, and the shipping industry to widely promote the vast benefits and opportunities of being part of a dynamic international industry and position itself as an industry of choice. A marketing based solution is needed for Human Resource Management to challenge the issues facing the industry. In a study of Vietnam, one of the emerging sources of labour supply, Nguyen et al. (2014) support the recommendation for the development of effectiv...