![]()

1

The Maya and Their History

The Ancient Maya and the Spanish Conquest

The Maya region is composed of the modern countries of Guatemala and Belize and small parts of Honduras and El Salvador, as well as all or parts of the Mexican states of Yucatán, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Chiapas. It is located entirely south of the Tropic of Cancer, and thus is in the “tropics.” The highland area, however (the mountains of Chiapas and Guatemala), have a temperate climate because of the high altitude, and thus some of the Maya region is decidedly nontropical. Nevertheless, most of the area is in lowlands and therefore is hot and humid virtually all year round. However, since the latitude is considerably north of the equator, there are distinct seasons. The rainy season is from June through October, and the dry season is predominant the rest of the year. All of this means that the Maya lived, and live, in an environment of great diversity ranging from hot tropical rainforests (in the Petén and the Usumacinta River basin) to cold mountains (especially the Cuchumatán Highlands of west-central Guatemala).

The Maya took advantage of their environment to produce a wide range of agricultural and forest products. Agriculture itself began in the region over four thousand years ago, perhaps as long as five or six thousand years ago. Although a variety of food crops eventually were developed, by far the most important was American corn, or maize. This became the staff of life, and was so important to the Maya that their religion taught them that the gods had created human beings out of corn. Maize agriculture was complemented by production of beans, squash, tomatoes, and chili peppers. Animal protein was not always part of the diet, for before the arrival of Europeans the only edible animals were turkey, deer, and iguana. Only the former was domesticated.

To understand the history of the Maya it is vital to take into account the productivity of agriculture. The technology may appear primitive to the modern observer, but it was very effective, allowing agriculturalists to produce not only for their own subsistence but also a surplus that was channeled away from the producers through taxation and markets. Agriculturalists got government and cultural activities in return for civil and religious taxes, and goods (salt, flint, tools, etc.) in return for mercantile exchange. The productivity of maize also allowed the Maya the time to produce cotton in addition to food crops. The raw cotton was eventually spun into thread and woven into textiles, which the Maya produced not only for their direct use but also to pay their taxes. Cloth was even used in commercial exchange as a kind of currency. Other Maya forms of money included cacao beans (small change) and jade (for high-value purchases).

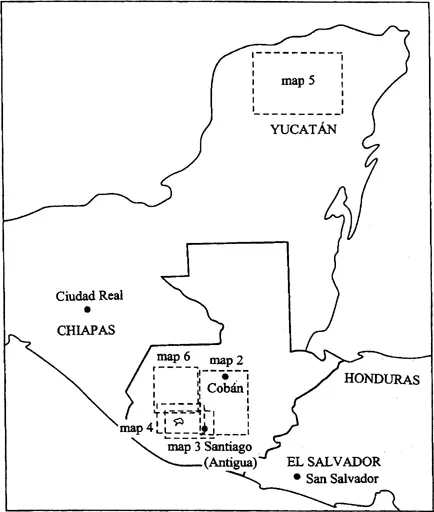

Map 1 The Maya Area Dotted lines show location of detailed maps appearing elsewhere in the book.

As a result of the great productivity of Maya agriculture, a complex society could be supported by the surplus channeled away from the peasants to higher social classes. Maya society eventually became quite stratified, with sharp distinctions made between the farming majority and the ruling elites. Those who ruled developed a strong sense of their special status by emphasizing their lineage and ancestry and by maintaining a monopoly on the skill of reading and writing. They also established a tradition of strong village and regional government and of religious power. The division of society into classes and the institutionalization of political and religious power were characteristics of the Maya that in retrospect helped them survive the extreme dislocation caused by Spanish conquest. At the same time the structure of Maya society and politics provided the Spaniards with the means of controlling the conquered people as well as the mechanisms for extracting wealth from the surplus-producing peasantry.

The ancient Maya were never able to attain political unity. At all times the area was divided into numerous petty states based on capital cities or towns. These engaged in perennial warfare with each other, a practice that served to provide aggressors with captives who could be sold as slaves and exported to other regions, including central Mexico. Some captives, especially high-ranking ones, also became sacrificial victims.

By the early sixteenth century, when the Spaniards arrived on the scene, the Maya area contained a large number of small political states. Yucatán, despite the linguistic unity of the Yucatec Maya, had sixteen or so of these regionally based political units.1 The highland areas were even more complex, because the people were divided linguistically as well as politically. Some, but not all, of the linguistic groups seem to have formed political units that united all the people of the same language. This was the case among the Cakchiquel and Quiché people of the central highlands of Guatemala, but such political and linguistic unity was not found everywhere.

The results of this political fragmentation were important. On the one hand, it meant that ultimate Spanish victory was virtually certain, for the invaders could pursue a typical policy of “divide and rule”: they could make alliances with some people in order to conquer the others and bring all under their control one by one. On the other hand, fragmentation helped delay conquest because for the Spaniards there was no single site to capture or one single government that could be forced to surrender. Conquest took time, which worked to the advantage of the Maya, for over time Spanish enthusiasm for conquest weakened. This was because the area’s lack of gold or silver to loot was discouraging, and because the discovery of Peru’s resources encouraged many Spaniards to leave the Maya area and seek their fortunes elsewhere. It therefore took over twenty years to bring most of the Maya under Spanish authority, a process that at times—as in the Verapaz region (the northern part of the Guatemalan highlands)—involved a negotiated submission rather than a surrender. In the Petén area of northern Guatemala some Maya remained unconquered and maintained their independence until 1697.2 Such regional variations, caused in part by preconquest political regionalization, would eventually play an important role in colonial politics.

The Ordering of Colonial Society

The Spanish conquest brought not only violence but also epidemic disease. In fact, the diseases preceded the arrival of the conquistadors and undoubtedly contributed to ultimate Spanish victory. The result of the epidemics of smallpox and other illnesses was a sharp population decline that continued throughout the sixteenth century. The demographic contraction was undoubtedly made worse by the forced resettlement (reducción or congregación) of the native people into larger, more concentrated settlements, a policy carried out by Spanish priests in order to “civilize” the Maya and make them easier to indoctrinate. Recovery of the population began in most places early in the next century, but then epidemics of yellow fever and other diseases once more caused decline. Only in the eighteenth century would demographic expansion take place in almost all parts of the Maya area.3

The institutions of colonialism imposed a structure on Indians all over America, and gave similarity to the history of socially complex, surplus-producing indigenous peoples from Mexico to Peru and even as far away as the Philippines.4 Nevertheless, local conditions of geography and variations in culture and in social and political structures determined the ways in which native society and colonialism adapted to each other. In the Maya area the absence of gold and silver deposits on a significant scale meant that the Spanish colonists could not enrich themselves as easily as in Mexico and Peru. Spaniards therefore looked for other exportable goods, and at first found one in cacao, much in demand in Mexico and then in Europe. But because cacao could only be produced in the lowlands, which were most exposed to tropical diseases, the indigenous population in the producing areas—Soconusco (the Pacific coast of modern-day Chiapas5), the alcaldía mayor (high magistracy) of San Antonio Suchitepéquez (the western Pacific coast of Guatemala), and Tabasco (on the southernmost coast of the Gulf of Mexico)—declined more drastically than elsewhere, thus severely limiting the supply of laborers and reducing output and profits.6 In the absence of an economy based on the export of raw materials, Indian labor was not as valuable as in some other regions of the Spanish empire. The labor draft demanded of the Maya (discussed in Chapter 4) for the most part involved the allocation of workers to local agricultural enterprises rather than to distant mining camps as in Peru and parts of southern Mexico.

Spaniards thus eventually came to realize that the most important source of wealth in the Maya area was the indigenous population and its economy. These the colonists learned to exploit through taxation and commercial exchange. Civil taxes, called tribute, were collected at first in kind (mostly corn, turkeys, cotton textiles, and where possible cacao) and later in silver coin as well as in kind. At first individual Spaniards, as rewards for their participation in the conquest, were given the right to collect tribute from a specific village or villages in return for their services in the conquest. This institution was called the encomienda, and the people with the right to collect tribute were called encomenderos. As time went on the Spanish crown, which feared that the encomenderos would become too powerful and too independent of Spain, gradually ended the encomienda system and took control of tribute. By the late seventeenth century, most of the Maya of Guatemala and Chiapas paid their tribute to the Spanish government rather than to an encomendero. By the 1720s all encomiendas were abolished in Guatemala and Chiapas; thereafter the Maya paid their tribute to the crown rather than to a private individual. In Yucatán, however, because of the lack of economic resources available to the Spanish colonists, the government allowed the encomienda system to continue to exist until 1785.

The Maya also had to pay religious taxes, which were the ecclesiastical equivalent of tribute. The conquered people paid at first in kind, and later in kind and in money, in the same goods as in the tribute system. The taxes so collected were used to provide for the local church and priest, not for the diocese as a whole. At the same time, Indians were also required to tithe, that is, pay one-tenth of their annual production. Tithes, which Spaniards also had to pay, went directly to the ecclesiastical government of the diocese, and provided an income for the bishop and other priests who administered the church. However, the crown also got a share, usually two-ninths of the total, and thus had a vested interest in seeing that everyone paid what was owed. Nevertheless, the tithe, unlike other religious taxes, had little impact on the Maya. This was because the crown eventually decided that the Indians would pay this tax not on all their production but only on those goods that were not of indigenous origin (in other words, wheat, cattle, sheep, pigs, and chickens). Since the Maya economy was based overwhelmingly on native products, especially corn, the tithe was an insignificant burden on the Indians.

As a result, and because the Spaniards engaged in few productive activities that would produce significant tithe revenues, the Catholic Church in Guatemala and Yucatán was quite poor. In Guatemala the government paid a subsidy to local priests who otherwise would have found it difficult to make ends meet. Indeed, the clergy was so poor that few people wanted to be priests, and as a result the diocese had to rely on friars who took vows of poverty. As a result, until the middle of the eighteenth century almost all rural parishes in Guatemala and half of those in Yucatán were under the care of Dominicans, Franciscans, or Mercedarians.7

Commercial exchange was the other mechanism that the Spaniards used to extract wealth from the Maya. By far the most important practice accomplishing this was the system known as the repartimiento (not to be confused with a labor draft also called a repartimiento). This came into existence in the late sixteenth century and continually increased in importance until, by the middle of the eighteenth century, it frequently had become the most important mechanism for extracting a surplus from the Maya. The commercial repartimiento was a system of business transactions between Spanish government officials and the Indians under their jurisdiction. The official, usually an alcalde mayor (high magistrate), a corregidor (magistrate), or a governor, would either sell goods to the Indians at prices favorable to the seller or would buy goods at prices favorable to the buyer. In the first case, the magistrate would usually sell livestock, agricultural tools, or clothing for much more than he paid for the goods and thus make a large profit on the transaction. The second case, the purchase of goods from the Maya, was the most important form of repartimiento. This consisted of the payment in advance, and of course at low prices, for goods that the Indians produced. Most commonly, the alcalde mayor, corregidor, or governor would loan money to the Maya so that they could pay their tribute, and then would collect the debt in cotton or woolen textiles, raw cotton or wool, wheat, cacao, or wax. He would then resell the goods at market prices, which were much higher than the value of the credit given to the Indians. This of course also allowed the magistrate to make a large profit on his dealings with the Maya.

The significance of tribute (whether collected by encomenderos or by the crown), religious taxes, and the commercial repartimiento is that they were mechanisms for the extraction of wealth from the Indians in ways that did not seriously disrupt the Maya economy. The goods in question were almost always those of the native economy; new economic activities that might have been disruptive, such as silver mining, did not have to be introduced. Taxes and the repartimiento, in short, depended not on new structures of production but rather on already existing ones.

Since corn was bulky, expensive to ship, and subject to spoilage, by far the most important native products from the Spanish point of view were cotton textiles, for which the Maya are famous. Cotton was produced through-out the lowlands and then shipped to all Maya communities for spinning and weaving. Spanish encomenderos, officials, and priests demanded partial payment of tribute and religious taxes in cotton textiles.

Eventually the acquisition of cloth manufactured by the Maya became the most important branch of the commercial repartimiento as well as of tribute and religious taxes. Cotton was planted and harvested by men and boys, and spinning and weaving were carried out by women and girls, so tribute, taxes, and the repartimiento ensured that the agents of colonialism tapped the surplus labor of everyone—men, women, and children—in the peasant community.8

The royal government prohibited its officials in America from engaging in commercial enterprises within the areas of their jurisdiction. This meant that the repartimiento was illegal. However, the crown did legalize it in Yucatán in 1732, and it remained legal in that province until the 1780s. In Guatemala the repartimiento was legal only for one decade—the 1750s. For most of the colonial period, therefore, this system of economic exchange between the Maya and the Spanish magistrates was illegal. It nevertheless was widely practiced in both Yucatán and Guatemala, legally or otherwise. The repartimiento existed and survived numerous edicts against it because it enabled the poorly paid colonial magistrates to earn extra income and thus was an unofficial encouragement to take up an office with a low salary. The crown in fact tolerated the system, for it permitted the government to pay low salaries and thus keep administrative costs down.

The repartimiento was important because it allowed Spanish corregidores, alcaldes mayores, and governors to acquire valuable goods much below the market price. The cotton textiles acquired through repartimiento, tribute, and religious taxes were of vital importance because, with the exception of wax and a little cacao, they were the only ...