- 420 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

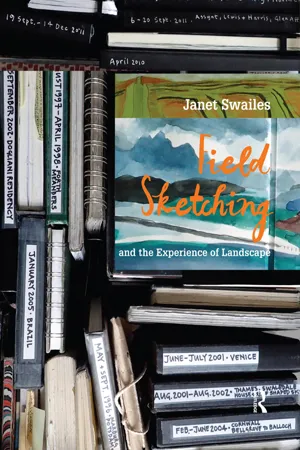

Field Sketching and the Experience of Landscape

About This Book

The act of field sketching allows us to experience the landscape first-hand – rather than reliance upon plans, maps and photographs at a distance, back in the studio. Aimed primarily at landscape architects, Janet Swailes takes the reader on a journey through the art of field sketching, providing guidance and tips to develop skills from those starting out on a design course, to those looking to improve their sketching.

Combining techniques from landscape architecture and the craft and sensibilities of arts practice, she invites us to experience sensations directly out in the field to enrich our work: to look closely at the effects of light and weather; understand the lie and shapes of the land through travel and walking; and to consider lines of sight from the inside out as well as outside in.

Full colour throughout with examples, checklists and case studies of other sketchers' methods, this is an inspirational book to encourage landscape architects to spend more time in the field and reconnect with the basics of design through drawing practice.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Part 1

Reviewing Field Sketching as a Contemporary Practice

Part 1

Introduction

Chapter 1

Practice: Field sketching

What is a field sketch?

The notion of a sketch

- to find the gist or essence of a subject, and as a way to capture an impression;

- as practice for drawing, particularly helpful in loosening up;

- to collect data for another purpose, such as a painting;

- to record nature, through either a more involved naturalist study, or by just catching a moment;

- as a visual diary, or memory jogger;

- for enjoyment, being outside in the elements, for relaxation and meditation, or the pleasure of caricature.

Sketching or drawing?

Trends in field sketching practice

What practitioners say about sketching and sketchbooks

Landscape architects

- Generally, sketching is regarded as a quick drawing activity, with typical periods varying between sketchers: ‘10 seconds to 15 minutes. I haven’t the patience for anything longer … 20 to 30 minutes. … an excuse to slow down … I will stop for 10, 15, 20 minutes. At the most, I’ll spend two hours on a sketch, but very few take more than a couple of hours.’

- The process of sketching is organic; the sketch arising out of its circumstances and time available: ‘The elements themselves or those around me impose those limits … First you must see the critical elements to form and set those down on the page, then the second most critical, and so on … the sketch is what it is.’

- Issues of when to start, when to stop, how to keep motivated, letting go, are all concerns. The processes of movement through landscapes and drawing have their own dynamic and making a sketch becomes a period of attunement.

Artists

Background and history

Observational drawing in pursuit of understanding

Map making

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 Reviewing Field Sketching as a Contemporary Practice

- 1 Practice: Field sketching

- 2 Practice: Changes in how we think about perception

- 3 Practice: Theory, ideas and arts practice

- Part 2 Developing the Technique of Field Sketching

- 4 Technique: Towards an integrated visual and experiential approach

- 5 Technique: Fieldwork and field notation 1

- 6 Technique: Drawing in the field 1

- Part 3 Core Skills

- 7 Core skills: Fieldwork and field notation 2

- 8 Core skills: Drawing in the field 2

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index