![]()

1

THE DYNAMICS OF THE MIDDLE CLASS IN AFRICA

Charles Leyeka Lufumpa, Maurice Mubila, and Mohamed Safouane Ben Aïssa

Introduction

Empirical evidence shows that the growth of the middle class is associated with better governance, economic advancement, and poverty reduction. As people gain middle-class status, they are more likely to use their greater economic clout to demand more accountability and transparency from their governments (Lipset, 1969; Asian Development Bank, 2010). This includes pressing for the rule of law, clearer property rights, and a higher quality of public service provision.

Robust economic growth in Africa over the past two decades has been accompanied by the emergence of a sizable middle class and a significant reduction in poverty. There has also been a concomitant increase in consumption spending. Indeed, consumption in the continent now stands close to one-third that of developing EU countries.

Fostering the growth of the middle class should be of primary interest to policymakers. It represents a strong medium- and long-term development indicator, partly because of its close association with accelerated poverty reduction. This provides an opportunity for African governments to leverage middle-class growth to accelerate poverty reduction by harnessing appropriate policies.

This chapter argues that the middle class holds the key to a rebalancing of African economies toward greater dependency on domestic demand rather than an over-reliance on export markets. The evidence presented here is based on research and studies undertaken in 45 African countries.

Definitional issues, data sources, and methodology

Who are ‘the middle class’?

The middle class can be defined in relative or absolute terms. In relative terms, the middle class refers to households falling between the 20th and 80th percentile of the consumption distribution, or individuals falling between 0.75 and 1.25 times median per capita income (Birdsall, Graham, and Pettinato, 2000). Using the absolute definition, the middle class usually refers to individuals with an annual income exceeding $3,900 in PPP terms (Bhalla, 2009). Banerjee and Duflo (2008) consider two separate groups: (i) those with a daily per capita expenditure between $2 and $4 and (ii) those with a daily per capita expenditure between $6 and $10.

The middle class is widely acknowledged to represent Africa’s future, as the group crucial to the continent’s economic and social development (McConnell, 2010). But it is difficult to define exactly who falls into this category and harder still to establish how many middle-class people there are in Africa. Recent estimates put the size of the African middle class in the region of 300 to 500 million people, representing the segment of population that lies between the vast number of the poor and the continent’s few elite. Africa’s emerging middle class is thus roughly the size of the middle class in India or China (Mahajan, 2009). It is also argued that this segment of the population is strongest in countries that have robust and growing private sectors (Ramachandran, Gelb, and Shah, 2009). The middle class is crucial not only for the growth of Africa’s economy but also for the growth of democracy.

Definition used in this chapter

This chapter uses an absolute definition of per capita daily consumption of $2–$20 in 2005 PPP US dollars to characterize the middle class in Africa. The study provides three subcategories of the middle class. The first is that of the ‘floating class,’ with per capita consumption levels of $2–$4 per day. Individuals with this level of consumption are only slightly above the developing-world poverty threshold of $2 per day, which is used in some studies (Ravallion, Chen, and Sangraula, 2008). Such people are at risk of relapsing into poverty in the event of exogenous shocks such as a rise in the price of foodstuffs or loss of income. This ‘floating class’ subcategory is the demarcation between the poor and lower-middle class. This class is vulnerable and unstable, but it reflects the direction of change in population structure over time.

The second subcategory is that of the ‘lower-middle class,’ with per capita consumption levels of $4–$10 per day. This group lives above the subsistence level and is able to save and consume non-essential goods. The third subcategory is the ‘upper-middle class,’ with per capita consumption levels of $10–$20 per day.

Data sources

A variety of data sources were used in our study to create the population distributions and determine the size of the African middle class. The primary source for the distribution data is the World Bank’s PovcalNet database, updated for 2012, which provides detailed distributions of either income or household consumption expenditures by percentile, based on household survey data. In addition, PovcalNet provides information on mean household per capita income or consumption levels in 2005 PPP US dollars.

This database primarily provides sample distributions based on consumption, except in instances where only income measures exist. At lower income levels, the difference between consumption and income is small. However, this difference increases with wealth and thus should be considered a potential measurement error in the analysis. Nevertheless, we expect these differences to be relatively minor, as there is generally a high correlation between income and consumption and thus they should have little effect on overall computations. We also focus on consumption, as it better captures individual welfare and is less prone to fluctuations caused by negative and positive shocks.

The data used in the identification of the characteristics of the middle class were obtained mainly from the AfDB Data Portal and other international sources (Penn World Table, 2009; UNU-WIDER World Income Inequality Database, Version 2.0c 2008; also see Appendix 1.4).

Methodological approach1

The tabulated distributions and their means are used to generate a Lorenz curve for each country to show the share of income for each subclass of the population. The line of equality depicts a situation of perfect equality in a society where a given proportion of the society would have an equal proportion of the income. The extreme opposite would be where an individual has all the income while everyone else has none. The Lorenz curve is normally used to represent inequality in the distribution of income among the population. The further the curve is away from the line of equality, the more unequal is the income distribution in a given society. The Gini coefficient also measures levels of inequality and is derived from the Lorenz curve. It represents the proportion of the area between the line of equality and the Lorenz curve and the total area above and below the Lorenz curve.

The literature on the estimation of Lorenz curves provides a number of different functional forms. Two of the best performers are the general quadratic (GQ) Lorenz curve (Villasenor and Arnold, 1984, 1989) and what may be called the Beta Lorenz curve (Kakwani, 1980). There is some evidence from Indonesia that the Beta model yields more accurate predictions of the Lorenz ordinates at the lower end of the distribution, though the same study found that the GQ model is more accurate over the whole distribution (Ravallion and Huppi, 1990). The GQ model, however, does have one comparative advantage over the Beta model, in that it is computationally simpler (Datt, 1998).

This chapter therefore uses the Beta approach for estimating the various points of the Lorenz curve, showing the proportion of the population and their share of national income (see Appendices 1.1 and 1.2). Using a system of six equations, each representing a trapezoid-shaped area under the Lorenz curve for a series of coordinates, we obtain three unique values representing the proportions of the population associated with the per capita daily income levels of $4, $10, and $20 (see Appendices 1.1 and 1.2). These represent the floating class, the lower-middle class, and the upper-middle class subclasses defined by this chapter.

Africa’s emerging middle class

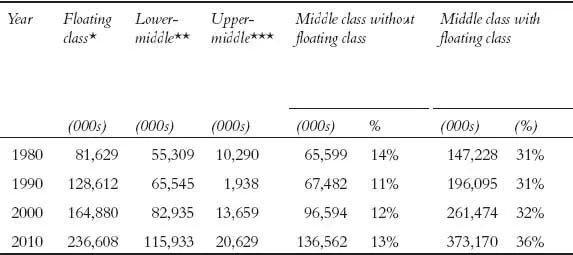

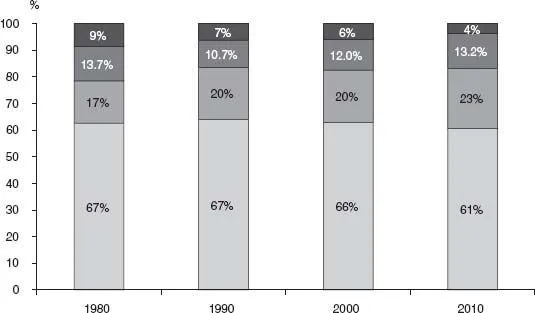

The results of our study reveal that Africa’s middle class has increased in size and purchasing power as strong economic growth over the past two decades has helped to reduce poverty. By 2010, the middle class (including the floating class) had risen to 34 percent of the population (373 million people) (see Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1). This shows a progressive increase over the previous 30 years, from 147 million in 1980, to 196 million in 1990, to 261 million in 2000.

TABLE 1.1 Distribution of Africa’s population by subclass, 1980–2010

Source: AfDB Statistics Department.

Notes: *Floating class ($2–$4), ** Lower-middle class ($4–$10), *** Upper-middle class ($10–$20), 2010 figures revised based on updated data in PovcalNet in 2012.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the slow growth of the middle class meant that only a small percentage of poor households were becoming better off. This trend accelerated slightly during 2000–2010, when a greater number of poor households transitioned into the middle class. At the same time, the decade of the 2000s witnessed an opposite movement – from the rich into the middle class, implying a slight rebalancing toward greater income equality. However, income inequality in Africa remains very high. About 100,000 Africans recorded a net worth of $800 billion in 2008, which equates to about 60 percent of Africa’s GDP or 80 percent of SSA’s GDP (Merrill Lynch, 2010).

FIGURE 1.1 Distribution of Africa’s population by subclass, 1980–2010 (source: authors’ calculations based on AfDB Data Portal and World Bank PovcalN...