![]()

1

Introduction: The Rise of the Semiglobal Economy

Strategy assumes its rightful place in the hierarchy of decision making when it’s part of the business model: integrated with the realities of the external environment, the financial targets, and the business’s operating, people, and organizational activities.1

We must continue to pursue multiple strategies and parallel initiatives to ensure that we are offering the right mix of brands and benefits to our customers and the optimal combination of profitability and service for our customers.2

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, business strategists advised corporate executives to abandon the traditional hierarchical model of business organization for a modem non-hierarchical model: level corporate hierarchies, narrow product portfolios, and organize production by activity rather than by task. The basic premise for this paradigm shift was a self-evident trend, the turning of the world economy from a multinational market, a collection of separate national and local markets, into a global market, a single integrated market. This book argues that in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century, this premise is no longer self-evident. The world economy, or at least parts of it, is not turning into a global but into a semiglobal market, and competing in this market requires a new business model, the semiglobal corporation, which combines the two organizations rather than substitutes the one for the other.

When globalization resumed its course in the mid-1970s, it seemed a universal trend that would eventually turn every industry and every region of the world economy into a single integrated market, where commodities and resources would flow freely across consumer-homogeneous local, national, and international markets, and location would no longer be a source of competitive advantage. From the late 1970s to the mid-1990s, world merchandise exports rose from 11 to 18 percent of world GDP, and service exports from 15 percent to over 22 percent, while sales by foreign affiliates exceeded the world’s total exports.3 Foreign direct investment (FDI) outflow rose by 28.3 percent in the period 1986–90 and by 5.6 percent in the period 1991–93. World cross-border credit to non-banks soared from $766.8 billion in 1984 to $2,502.3 billion in 1994. Globalization accelerated in the early to mid-1990s as the diffusion of information technology and the establishment of North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and World Trade Organization (WTO) accelerated cross-border trade. Trade flows between Canada and Mexico on the one side and the United States on the other almost tripled, while world capital imports grew at a double-digit rate.

By the middle of the first decade of the new millennium, globalization no longer seems a universal trend, for several reasons. First, economic integration has advanced in different gears across world regions and countries. Economic integration advanced in a high gear in countries like Ireland, Finland, and Switzerland, and in a low gear in countries like Israel, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, while it has remained stuck in neutral in many African and Southeast Asian countries that continue to remain on the sidelines of the global economy.

The poorest countries (for example, in Africa) have been left out of the process of economic development. Even within developed or rich countries, the long-ran evolutions of Great Britain and Argentina remind us that relative or absolute decline is always a possibility and that convergence is never automatic but is associated with the choice and implementation of an adequate strategy, given a changing international regime and a radical change in technological innovation.4

In 2005, market-opening reforms were concentrated in twenty-six OECD countries and in twenty-five east and central European countries and former Soviet republics. For the period 1990–2001, intra-trade in merchandise imports accounted for 60 percent of the European Union (15) trade, for 40 percent of NAFTA (3), and for around 22 percent of the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (10). Reflecting such a clustering of trade, most large companies conduct their business in these three areas.5 In the early years of this century, Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s merchandise trade (exports plus imports) account has accounted for about 150 percent of GDP compared to Pakistan’s 20 percent. As of 2002, close to 60 percent of world trade was concentrated among ten countries; and 33 percent among three countries, the United States, Germany, and Japan.6 Ten countries received 80 percent of global investment flows, while the majority of cross-border acquisitions occurred in high-income countries, most notably in the United States, Canada, France, and Germany; 84 percent of newly acquired or established U.S. multinational affiliates were located in developed countries.7

Second, economic integration has advanced in different gears across industries. Economic integration is shifting to a higher gear in textiles, as a 1974 trade pact expires, eliminating a number of quotas and tariffs that limited the flow of garments from developing to developed countries. Economic integration is also shifting to a higher gear in services that have become the target of a new wave of outsourcing. Globalization remains in low gear in a number of industries that continue to be dominated by “local clusters,” geographic concentrations of companies related by common skills, technology, inputs, regulatory frameworks, and culture, like those of Silicon Valley, Napa Valley, Hollywood, and Sanjyo (Niigata, Japan). Commodities and resources cannot flow freely across markets, and location continues to be a source of competitive advantage. “Paradoxically, the enduring competitive advantages in a global economy lie increasingly in local things—knowledge, relationships, and motivations that distant rivals cannot match.”8

Economic integration has shifted into reverse gear in a third group of industries that have regressed to trade protectionism and government regulation. The steel industry is a case in point. In December 2001, citing a surge in imports in twelve steel products, the United States imposed ad valorem duties ranging from 8 to 40 percent, and tariff-based quotas up to 20 percent. The food industry is another case in point. The EU has banned genetically engineered altered products, a ban that hurts American farmers, while the United States requires producer registration and early import notification, slowing the flow of goods in local markets. Compounding the problem, concern over the spread of terrorism has slowed down the flow of resources and commodities across national borders.9 Business travelers take longer to obtain visas, slowing down trading in sophisticated equipment, like aerospace products and metal cutting machines, that must be inspected by customers before shipment. Some observers go so far as to declare the end of globalization.10

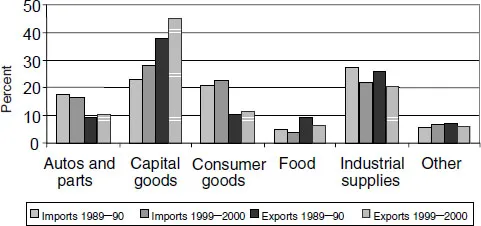

As economic integration shifts to different gears across industries, so do trade flows. The WTO reports that for the period 1990–2001, exports of industries at the center of trade liberalization, like machinery and transportation equipment and office and telecom equipment, have experienced the highest growth, while exports of industries still under protection, like food and industrial supplies, have experienced the slowest growth. The 2001 Economic Report of the President (USA) finds that capital goods, consumer goods, and auto parts are highly globalized, while industrial supplies and food sectors are less globalized. U.S. capital goods imports, for instance, increased from 23 percent in 1989–90 to 28.2 percent in 1999–2000, while exports increased from 37.8 percent to 44.8 percent. Food imports increased by 5.2 percent in 1989–90 and 3.9 percent in 1999–2000, while exports increased by 9.4 percent in 1989–90 and 6.3 in 1999–2000 (Figure 1.1). Trade flows have shifted to a lower gear in less globalized industries, such as repair and maintenance services, credit origination services, entertainment, and medical care services that are localized. For the period 1990–2002, the share of transportation and travel service exports has declined while the share of other commercial services has increased (see Figure 1.2). Global trade in services has declined by 1.3 percent, while global foreign direct investment dropped by 53 percent. In 2001, global merchandise trade slumped by 43 percent to $6.08 trillion, the first decline since 2001, dragged down by a decline in information technology trade, which accounted for 60 percent of that decline.

Source: Data were taken from Survey of Current Business, various issues.

Figure 1.1 U.S. Trade Flows for Highly Globalized and Highly Localized Industries, 1989–90 and 1999–2000

Third, international businesses continue to face local consumer diversity. For many products, consumers retain their preferences even within highly integrated regions, such as the European Union, NAFTA, and Asian Pacific Economic Council. The preferences of Greek consumers, for instance, are different from those of other southern Europeans, and most notably from those of northern Europeans; and the preferences of Mexicans are different from those of North Americans. The preferences of Asians differ from those of both Europeans and Americans. For large, multicultural countries like China and India, consumer preferences differ not only from those of developed countries, but from one region to another and from one city to the next.11 In some cases, local variations in consumer preferences are not pronounced in product selection...