1.1 Context for this book

Desktop computers were introduced in the 1980s and during that decade hardware manufacturers and software publishers realized that in order to sell their products in other markets or countries, they would need to adapt them so that they would still be functional in different environments. This adaptation became known as localization since target countries or groups of countries were also referred to as locales. Localization was required because computers at the time relied on very different character sets so a program written in, say, Spanish and encoded in a Western encoding would not run properly on a Japanese operating system. Since then, localization processes have become more sophisticated and are often coupled with internationalization processes, which aim at preparing a product for localization. Note that, because of the length of the words internationalization and localization, the words are commonly shortened to i18n and l10n. These acronyms are ‘quoting the first and last letter of each word, and replacing the run of intermediate letters by a number merely telling how many such letters there are.’1 Adapting a product to a specific market or locale is of course not specific to the Information Technology (IT) industry, as any business hoping to operate successfully on a global scale is likely to rely on transformation processes so that their equipment, medicines or food products meet, or even exceed local regulations, customs and expectations. In this book, however, the focus is on software applications, which are also referred to as applications or apps.

1.1.1 Everything is an app

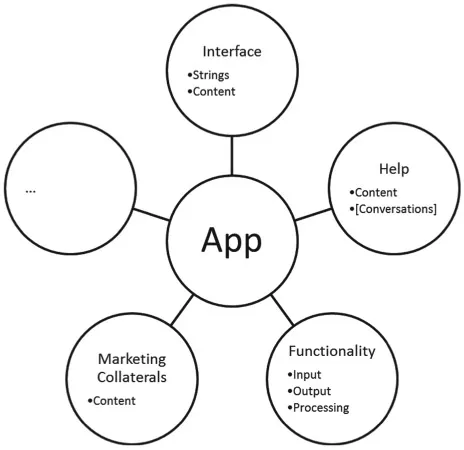

To an end-user, an app is often limited to the visual interface they use to accomplish a specific task. Depending on the complexity of the task(s) an app is supposed to perform, additional components may become apparent over time. Such components can be referred to as an application’s digital ecosystem, a non-exhaustive example of which is presented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Components of a software application’s ecosystem

Most of these components should be familiar to anybody who has ever come across a software application in their life (be it a desktop application, a mobile application or a Web-based application). An application is obviously equipped with an interface, which is composed of textual strings (e.g. menu items) and content (e.g. informative content such as news items or pictures). While most app users probably know that help content is also available, finding and using such content is not as frequent as using the actual application’s functionality (which is why help or support often takes place through online or physical conversations). An application’s functionality often relies on user input which must be processed using procedures or algorithms in order to generate some output. Depending on the type of application, some marketing, training and sales-related content may also be generated, but this may not be as relevant from an end user’s perspective. Figure 1.1 shows, however, that the ecosystem surrounding an application can become quite large if the application turns out to be a success. As far as this book is concerned, the focus is placed on those components that make apps different from other content types (e.g. a perfume’s marketing brochure or a drugs information leaflet), thus requiring specific processes such as localization.

While software localization emerged in the IT sector, it is now prevalent in other sectors, especially those that have an online presence, be it through Web sites (which are very often indistinguishable from Web applications) or Web services. Any online digital content that is generated by online systems or apps, can now be subject to some form of localization in order to reach as many users as possible. In this sense, no conceptual distinction is made in this book between Web sites, mobile apps or desktop programs: all of these are apps, whose digital ecosystem may vary in size depending on its user base. It should be stressed that contributions to this digital ecosystem need not solely originate from an authoritative app developer or publisher. App users are now increasingly directly and indirectly taking part in various aspects of an application’s lifecycle, ranging from funding and suggesting features to testing and writing reviews. For instance, Kohavi et al. (2009: 177) explain that ‘software organizations shipping classical software developed a culture where features [were] completely designed prior to implementation. In a Web world, we can integrate customer feedback directly through prototypes and experimentation.’ With the Web 2.0 paradigm, publishing cycles have also been dramatically reduced, thanks to easy-to-use online services including collaboration tools. These tools and services have democratized the content creation process, which in turn has had an impact on localization-related processes.

1.1.2 The language challenge

Users are spending more and more time online, thus requiring content to be available in a language they can understand. A recent User language preferences survey conducted upon the request of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Information Society and Media (Gallup Organization 2002: xi) and it has never been more relevant than today. This is no surprise considering the ever-increasing amount of content to be translated in a very limited period of time. Even though localization does not only involve translation, publishers are often striving for a simultaneous publication of their information in multiple languages.

As far as multilingual Web sites are concerned, Esselink (2001: 17) warns that ‘the frequency of updates has raised the challenge of keeping all language versions in sync (…), requiring an extremely quick turnaround time for translations.’ However, providing information before it becomes obsolete is sometimes not possible for publishers, and some content is published exclusively in the language in which it has been authored. Yunker (2003: 75) remarks that ‘unless the target audience consists of only bilinguals, this approach is bound to leave people feeling left out.’ The lack of global distribution and accessibility has been highlighted by Pym (2004: 91) and is reflected by three types of locales: the participative locale consists of users who are able to access information in a language they can understand. These users are then able to act upon the information they have accessed. The observational locale consists of users for whom it is too late to do anything with the information they access. They are able to access it in their own language, but by the time this information is translated, it is obsolete. The excluded locale consists of users who are never given the chance to gain access to information in a language they can understand.

Giammarresi (2011: 17) mentions that there are two main reasons for a company to localize its products: a reactive approach ‘if one international customer has expressed interest in purchasing a localized version of one of the company’s products’ or a strategic approach ‘if the company has decided to expand into one or more new international markets’. While this may be the case in certain scenarios, two other reasons should also be mentioned: the interest of users (not necessarily customers) to help localize the product (from an altruistic perspective) and the laws and regulations that are in operation in certain countries. These four main factors driving localization-related activities (global user experience, revenue generation, altruism and regulations) are discussed next.

1.1.3 The need for localization

The first factor concerns the user experience. For instance, the User language preferences survey mentioned in the previous section found that while some users feel comfortable reading or watching Web content using a language which is different from their native language, a majority of users expect to be able to interact with content (search, write, manipulate) in the language of their choice (e.g. majority of Europeans). A slim majority (55 per cent) of Internet users in the EU said that they used at least one language other than their own to read or watch content on the Internet, while 44 per cent said that they only used their own language. These numbers are more or less aligned with the survey carried out by the International Data Corporation in 2000 within the framework of the Atlas II project. Based on the results obtained from 29,000 Web users, they had estimated that by 2003, 50 per cent of Web users in Europe would be likely to favour sites in their native language (Myerson 2001: 14). These findings suggest that in order to provide a truly comfortable user experience, Web sites should offer some language support, which may involve some form of content localization (and possibly internationalization). Regardless of the reasons for not fully localizing online content (time, cost, lack of resources), the consequences of having content that is only partly localized should not be underestimated.

The second factor is revenue generation. A Common Sense Advisory report found that a major driver for any corporate involvement in global markets is always new revenue and market share opportunities.2 DePalma et al. (2011: 2) report that ‘high-tech hardware and equipment makers generate more than a quarter (27.1 per cent) of their revenue account from global markets [and] oil and gas companies earn 23.6 per cent of their income outside the United States.’ In order to be able to compete in these markets, however, companies often have to break the language barrier, and localize some of their content, products or services. Since this requires an upfront investment, these companies must have some level of confidence that this investment will be justified, or that they will get some Return On their Investment (ROI). According to Zouncourides-Lull (2011: 81), it is therefore common in localization projects to calculate costs ‘using parametric estimation, by applying standard rates (e.g. cost per word) and possible revenue’. The pervasive use of translation memory technology has greatly influenced this approach, by providing a quick way to calculate how much it would cost to translate new or legacy content. When these ROI calculations fail to convince executive sponsors, or when the prospect of having to manage and support a number of languages is too daunting, language barriers remain, and opportunities are lost. This is particularly visible with smaller companies, which do not necessarily have the budgets or expertise to embrace localization. For instance, a recent nationwide survey of Irish hotels has found that only 18 per cent of those sampled offer languages other than English on their Web site.3

The third factor is altruism. When the opportunities described earlier are lost, volunteers sometimes decide to contribute some of their time to localize content. This is especially visible in the IT sector with open-source projects such as LibreOffice.4 Altruism also applies to Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) who rely on motivated volunteer translators. A recent survey conducted by O’Brien and Schäler (2010: 9) found that ‘support for [The Rosetta Foundation]’s cause and opportunities to increase professional experience emerged as the two greatest motivating factors’. Also, volunteer-based collaborative translation or crowdsourcing is becoming common in large for-profit corporations. This is especially the case when the product does not necessarily need to be released in a timely fashion or when the ROI for localizing the product is not convincing (but a lot of enthusiastic users are willing to contribute to the localization effort).

Finally, local laws play a very important role in determining whether and how content should be translated or localized, including, but not limited to, language laws, data protection laws and certification laws. In terms of European language laws, for example, the Toubon law in France, whose full name is Law 94-665 of 4 August 1994 (Article 2), mandates the usage of the French language when a product or service is presented, offered or described (e.g. in its user manual or terms and conditions).5 In Ireland, the Official Languages Act of 2003 provides a number of legal rights to Irish citizens with regard to their interactions with public bodies using the Irish language.6

Data protection laws also play a very important role when it comes to the handling of digital content. For instance, in Germany, the Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz or BDSG) of 1 January 1978 prohibits the collection, processing and use of personal data, unless it is explicitly permitted by law or approved, usually in writing, by the person concerned.7 This means applications must be localized appropriately from a functionality and location perspective when adapted for the German market.

Finally certification laws can also have an impact on the localization of an application. For example, the US Department of Commerce mentions that before being sold in China, software products need to be registered at the China Software Industry Association, and the registration approved by the Ministry of Information and Industry. Besides, American firms cannot register their product directly since registration must be made by a Chinese entity.8 This process is even more stringent for the sale of enterprise encryption software since it needs to comply with the Commercial Cryptography Administration Regulation.9 This example shows that local customs and regulations (including testing and inspection procedures) can increase the complexity of a localization project. While this type of example will not be treated in detail, it is a good reminder that localization is more than just translation.

At the time of writing, the localization industry is also influenced by a number of mega trends, including the increasing popularity of mobile platforms. These trends are creating new challenges, which are changing the way traditional localization is currently being done. Some of these challenges, ‘volume, access and personalization,’ were identified in...