![]()

Section 1

Introduction

![]()

Chapter 1

Stage Lighting in the Third Millennium

Technology is a gift of God. After the gift of life it is perhaps the greatest of God’s gifts. It is the mother of civilizations, of arts and of sciences.

—Freeman Dyson, physicist and mathematician

It’s a Saturday night and Sixth Street in downtown Austin is about to come alive with throngs of partiers, dancers, and music enthusiasts. Everyone is in a pleasant mood, with the notable exception of one irritated club manager who has an annoying problem. His club is about to open for the evening and he has no lighting operator for the venue’s state-of-the-art lighting system. His employee quit the previous night and the manager scarcely knows how to turn on the console or the lights, much less make them do the things that prompted the owner of the club to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on them. And on this night the entertainment is stand-up comedy on a temporary stage that, as of 6pm, is in total darkness. The presets that are stored in the console put all the light on the dance floor and none on the newly erected stage. Try as he might, the manager is unable to put any light whatsoever within several feet of where it needs to be. What’s a manager to do?

Luckily, one of the most talented lighting programmers in the city happened to be in the room running a crew who were setting up for the city-wide comedy festival. On a whim the manager asked him if he could somehow persuade the console to put some light on the stage where the comics would be performing. The programmer took pity on the manager and carved time out of his hectic show call to help out. The manager was so pleased that he offered the programmer a job on the spot at a rate of $200 per night, an offer that was politely declined. What the manager didn’t know was that he was about four times shy of the programmer’s regular day rate.

The single scene that the programmer recorded in the console will get the club through the night, and, chances are, the manager will find a programmer willing to take him up on his offer. The rate he’s offering is not bad for a non-touring gig with short hours, and there are plenty of programmers in Austin.

This true story illustrates the technology conundrum in the world of stage lighting: there’s a trade-off between capabilities and ease of operation. The more “automated” lighting becomes, the more skill is required to make it perform the most basic of tasks. The demand for more powerful consoles to quickly program larger and more complex lighting rigs has produced incredibly sophisticated technology that comes with a steep learning curve. In the days of conventional lighting it was simple to operate. You could physically focus each light and find a fader that would turn it on. In the worst-case scenario it might take you a minute or so to find the right fader for the light or lights you wanted to control. Today the simplest tasks can be the most challenging for the complete novice. Before you can play back a scene you first have to patch, program, and record it using hardware and software that can boggle the mind.

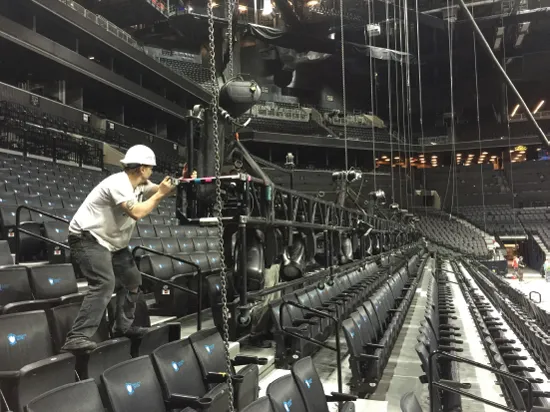

Figure 1.1 Lighting programmers who are fast, have a good attitude, and understand the technology are in the highest demand in the industry. Andrew Roman (left) and Kendall Clark (right) designed and programmed this lighting rig for the Louis the Child tour in fall 2016. (Photograph by Daniel Wyatt; equipment supplied by Creative Production & Design.)

The good news is that the demand for those who understand stage lighting is growing. Those who master the art of programming—and it truly is an art form—will always be in high demand. The quicker one can program, the more in demand they are and the more money they can earn—as long as they can interpret the lighting designer’s language, endure the long hours with a good attitude, and keep up with the technology (Figure 1.1). And the technology is always evolving.

Stage-Lighting Technology

Today’s stage-lighting systems are technological marvels with incredibly sophisticated hardware and software, a rich feature set, a high level of reliability, and amazing efficiency. They embody a wide range of disparate technologies, including optics, mechanics, robotics, chemistry, and electronics, mixed with a bit of ingenuity, artistic style, and design flair. Few products combine this level of sophistication and complexity in one package for the entertainment of the general public.

In stage-lighting fixtures, high-current devices like lamp circuitry reside in close proximity to high-speed, microelectronic components and circuits such as communications transmitters and digital signal processors. Voltages inside the fixtures range from a few volts to supply the electronics and motor-drive circuits to tens of thousands of volts to supply the starting circuit for arc lamps. The internal operating temperature can reach 1832°F (1000°C) in the optical path of a typical arc lamp stage-lighting fixture, yet the electronics are sensitive enough to require a reasonably cool environment to perform reliably. These fixtures regularly cycle between room temperature and operating temperature, placing great stresses and strains on the interfaces between glass, ceramics, metal, and plastics. At the same time many of the fixtures are designed to withstand the rigors of being shipped all over the world in freighters, airplanes, and trucks. They are often subject to daily handling and abuse from stage-hands, physical shock from being bounced around on moving trusses, and thermal shock from cycling on and off. They are truly an amazing blend of modern machinery, computer wizardry, and applied technology.

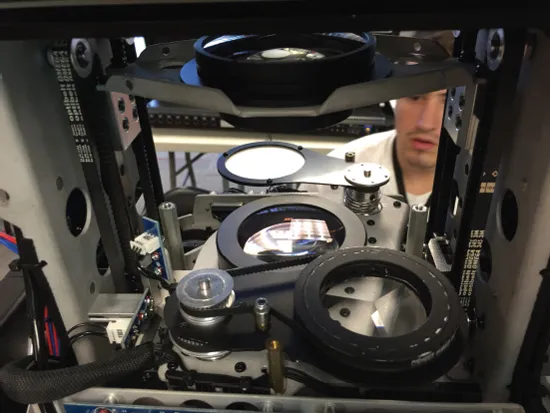

If you’ve ever seen the inside of an automated luminaire then you will have a sense of the complexity involved in its design. Design engineers draw from disciplines as diverse as physics, electrical and electronics engineering, software and firmware engineering, mechanical and chemical engineering, thermal engineering, and aesthetic design (Figure 1.2). These designers are under constant and intense pressure to innovate and leapfrog the competition before they are out-innovated. Innovation, whether it’s in pricing, performance, or feature set, is the only path to success and growth of the technology, as evidenced by some of the latest milestones in the industry. In the last 30-plus years there has been constant improvement in stage-lighting technology, but what has happened recently has really changed the landscape.

Figure 1.2 The design of stage lighting draws from a blend of physics, electrical and electronics engineering, software and firmware engineering, mechanical and chemical engineering, thermal engineering, and aesthetic design.

Wait, What Just Happened?

The only commercially available LEDs before 1992 were red, yellow, and green; there were no blue LEDs. In the late 1980s and early 1990s Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano were conducting research at Nagoya University in Japan in order to develop the elusive blue LED. They eventually succeeded in growing high-quality gallium nitride crystals that they needed to make it happen, and by 1992 had made their first blue emitters. Around the same time, Shuji Nakamura was working alone at a small company called Nichia when he developed a different method of growing gallium nitride crystals to make blue LEDs.

When they became a commercial reality, blue LEDs changed the world. They ushered in an era in which combining red, green, and blue LED light to create white light and a much broader gamut of colors opened the door to a host of new inventions, including LED video displays and color-changing light using solid-state emitters. Akasaki, Amano, and Nakamura received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2014 for the invention of the blue LED.

Another pivotal moment occurred in 1997, when the entertainment lighting industry gathered in Dallas for the annual Lighting Dimensions International (LDI) trade show. In the glass and steel structure of Infomart, a couple hundred exhibitors hoped to capture the imagination of the several thousand visitors. Among the exhibitors was a new company showing two products on a six-foot folding table that stood in contrast to the other excessively large booths, some as large as a concert stage and nearly as high. The two men behind the relatively small table were anxious to talk to anyone who stopped by their booth. The quirky-looking products looked something like a PAR 36 and PAR 46, except the light source was an array of red, green, and blue LEDs, which, at the time, was unheard of. Adding to the peculiarity was the relatively high price and the dismally low light output.

Some thought the lights were laughable, no more suited to lighting a stage than the gas lamps that came before electricity. But the two men, Ihor Lys and George Mueller, got the last laugh. The lights they were showing that year at LDI were some of the first offered by their company, Color Kinetics, which rapidly grew into a formidable power in the entertainment lighting industry. In 2007 they sold the company to Philips for $794m.1

How did they do it?

Though they were hardly bright enough to light the big stage, the products Color Kinetics displayed at LDI in 1997 impressed the judging committee enough to win the Architectural Lighting Product of the Year. These were some of the first LED lights for general illumination in the entertainment lighting industry, and, regardless of the light output at the time, they were unique—and Haitz law was on their side.

Dr Roland Haitz, the former CTO of Agilent Technologies, presented a paper in 2000 in which he observed that LEDs had increased in brightness by a factor of 20 while falling in price by a factor of 10 for each decade they had been in existence. With a blistering pace of development like that it’s no surprise that the issue of anemic light output was eventually overcome. In the long run, all doubts about whether or not LEDs could be bright enough to light a stage vanished in the harsh glare of the same lights that were once, in some people’s opinion, the laughing stock of the entertainment industry.

By the time Philips bought Color Kinetics the writing was on the wall, yet many in the industry remained dubious about the practicality of LEDs in entertainment lighting and whether or not they would ever be bright enough to compete with stage lighting. The answer, at least for the author, came breezing through town in the form of a touring band.

In December 2009 the band Daughtry was playing at the Frank Erwin Center on the campus of the University of Texas. Lighting designer Matt Mills had a mix of GLP Impression automated color wash LED fixtures and Martin MAC 2000 Profile fixtures on the stage (Figure 1.3). The MACs have a 1200-watt short arc lamp, and, to the naked eye, the two fixtures, which were no more than eight to 10 feet apart on the stage, looked to be about the same brightness. It was at that moment that the author knew LEDs had arrived on the big stage.

But brightness was only one issue LEDs had to overcome; steppy or choppy dimming was another. LEDs are so responsive that they tend to dim in steps rather than dim smoothly like an incandescent lamp. Manufacturers eventually figured out how to make them dim more smoothly by increasing the resolution or the number of dimming steps from blackout to full. But the bottom end of the dimming curve is especially tough to control, and LEDs would sometimes turn off in the last 1% of the dimming curve instead of smoothly fading to black like an incandescent lamp. That sudden drop from some light to no light is very unsettling to a lighting designer, especially when you’re used to the organic fade of an incandescent lamp. Today most high-quality LED stage lights have solved this problem to the extent that most mortals don’t notice a differen...