![]()

1 Introduction to Ancient China

Introduction

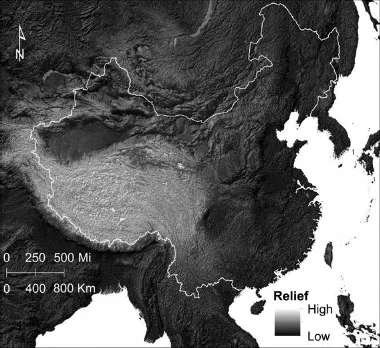

There was no such place as China for most of the time period covered by this book. Long before China arose as a concept, a place-name, and a political reality, a variety of cultures, polities, and states occupied parts of the physical landscape that we now know as China (Map 1.1). Some of the first manifestations of such cultures could be called “proto-Chinese” or “Sinitic”—that is, showing characteristics that would later be identified with China—while others clearly stood apart from the Chinese ethno-cultural world. The name China itself apparently comes from the state of Qin (pronounced “chin”), which in 221 BCE completed the forcible unification of the various states that occupied the Yellow River Plain and the Yangzi River Valley, imposed central rule upon them, and created the first authentic imperial Chinese state. But a succession of proto-states and kingdoms had existed in parts of that territory for some 2,000 years before “Qin” gave rise to “China,” and Neolithic cultures had existed there for thousands of years earlier. Indeed, human existence in various places in East Asia can be documented back over 50,000 years. How, then, is one to refer to China before “China”? And why does it matter?

It matters because the use of such terms as “North China” for the territory of the Shang kingdom (c. 1555–1046 BCE), or “Far Western China” for the Tarim Basin (the home of what seems to have been the easternmost outpost of the ancient people who would later be known as the Celts), tends to homogenize ancient history and obscure the diversity of the ancient East Asian world. It falsely suggests the existence of “China” as a political entity in very ancient times. And it obscures the reality that what is known as Chinese culture today has diverse regional and cultural roots.

Ancient China, as historians commonly use that term, refers to the period from the beginning of the Neolithic era, about 10,000 years ago, to the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty in 220 CE. “Early China,” in common usage, is a more restrictive term, used for the period from the Early Bronze Age to the end of the Eastern Han. The Three Kingdoms Period, 220–265 CE, marks the transition from Early China to Medieval China. In this book, we will generally avoid using the word China to refer to the period before 221 BCE. Instead we will refer to sociopolitical entities as they existed at any given time (for example, “the Shang kingdom” or “the state of Lu”), and locate them by using terms that refer to specific geographical features (“the Yellow River Plain,” “the South-Central Coastal Region”) rather than by such terms as “east-central China” or “the North China Plain.” Fortunately many Chinese place-names are geographically specific (such as the province names Shandong, “east of the mountain,” and Hunan, “south of the lake”), allowing us to use them freely within our frame of reference.

Map 1.1 Relief map of East Asia, with the present borders of China. Political boundaries change drastically over time; physical features are relatively much more stable.

Our basic focal area will be the East Asian Heartland Region and, surrounding it, the Extended East Asian Heartland Region. The first refers to the grain-growing regions roughly comprising the basins of the eastward-flowing Yellow and Yangzi River Valleys and the Sichuan Basin. The second, the Extended Heartland, encompasses the forests, grasslands, arid lands, mountains, high plateaus, and subtropical jungles that surround the Heartland Region. We will define these terms more precisely in Chapter 2; here we simply posit them as the landscape within which, over a long period of time, Sinitic culture and the Chinese nation gradually came into being.

Diversity and continuity in ancient China

To study the history of early China requires constantly navigating a course between two poles: change within continuity and continuity within change. In the long history of human societies in the East Asian Heartland we find both important structural commonalities and a wide range of cultural responses to widely differing environmental circumstances. Neolithic cultures worldwide are in some senses similar in their general characteristics (agriculture, villages, ceramics, stone tools), but highly diverse in the specific manifestations of those characteristics. The cultures of the Yellow River Plain, the Yangzi River Valley, and the southeastern coast, to name just three key regions, exhibit differences even today; the roots of those differences are unmistakably visible in the archaeological record over a period of 8,000 years or more and clearly reflect different ecologies and agricultural economies. For example, the people in the Yangzi River Valley mainly grew rice, while those in the Wei River Valley and the Yellow River Plain, to the north, grew several varieties of millet as well as barley and wheat. Coastal peoples in the south consumed large amounts of seafood and had access to abundant fruits and vegetables, both cultivated and gathered in the wild. Within some cultures hunting evolved from a daily pursuit to an elaborate and ceremonial elite activity, while elsewhere small populations of hunting and gathering tribal peoples continued to exist well into the era of dynastic states and great cities. Even when, over a period of many centuries, some northern and southern cultures in the two great river valleys began to amalgamate and coalesce into the root culture we call Chinese, many areas, large and small, remained unassimilated. During China’s first imperial period, the Qin–Han era lasting from 221 BCE to 220 CE, the empire struggled to define its relationship with the many non-Sinitic peoples within and along its borders. Substantial populations of ethnically non-Chinese people remain in the southern, western, and northern highlands to this day. In the early twenty-first century at least fifty-five languages are still spoken within the borders of the People’s Republic of China. It is reasonable to assume that in ancient times there was far greater ethnolinguistic diversity within the Heartland Region.

On the other hand it is equally true that a strong thread of cultural continuity runs though the Heartland Region’s tangle of cultural diversity. To that extent the oft-repeated claim that China has “the world’s oldest continuous civilization” can be taken as valid. The mask-like décor found on jade ritual objects of the Liangzhu Culture that flourished in the Yangzi River delta in the late fourth and early- to mid-third millennia BCE are clearly ancestral (with several intermediate steps) to the mask-like décor of bronze ritual objects of the Shang dynasty, 2,000 years later. Many shapes of ceramic vessels of the late Longshan Culture (c. 2600–2000 BCE) were directly copied in bronze during the Early Bronze Age Erlitou Culture and the subsequent Shang dynasty. Neolithic cultures in many parts of the Heartland, and their Jade Age and Bronze Age successors, exhibit a shared enthusiasm for the building of pounded-earth walls (village walls, city walls, eventually state-boundary walls), as well as a post-and-beam architectural style for large buildings, usually sited on pounded-earth platforms. The earliest known written language in the East Asian Heartland, found on animal bones and turtle shells used for divination during the late Shang Period, is unmistakably an early form of Chinese, and the subsequent written record shows the inexorable spread of Chinese as the region’s common language, leaving other languages to survive only in scattered pockets. Many other examples of long-term continuity will be adduced in this book’s pages, and because of that continuity we will often write in terms of “proto-Sinitic,” “Sinitic,” and (from the Qin–Han period onwards), “Chinese” culture.

Nevertheless, to say that there were fundamental continuities in the ancient East Asian Heartland is not to say that the region’s societies, whether in the emerging mainstream of Sinitic culture or on its fringes, remained static throughout time. Societies may change in response to internal evolutionary developments or external pressures, or both. They might even be swept away and replaced. For example, the Liangzhu Culture (c. 3200–2300 BCE) seems to have simply disappeared (possibly as result of a period of persistent flooding in the Liangzhu homeland in the Yangzi delta). Some attributes of Liangzhu Culture reappear in the Longshan Culture, which arose in western Shandong c. 2600 BCE and gradually spread widely across the Yellow River Plain; were those cultural attributes introduced by Liangzhu refugees who moved northward into Longshan territory? Or were they simply the result of long-term cultural contact? Did Longshan overlords conquer what remained of Liangzhu near the end of its cultural existence? And, in turn, did the final stage of the Longshan Culture lead directly into the beginning of the East Asian Bronze Age? Clear answers await further archaeological work.

New archaeological discoveries and new studies continue to redefine drastically our understanding of the cultural diversity of the ancient Heartland Region, and of the evolution there of political powers and of competing civilizations. It has revealed many early complex societies that were not recorded in the traditional histories but which must be taken into account to achieve a full and reliable picture of how China became China.

Eras, cultures, nations, states, and dynasties

Chinese history is conventionally divided into “dynasties,” defined as rule over all, or at least a substantial portion, of China’s territory from a politically symbolic center by a single lineage of kings or emperors over time. Thus it is commonplace to speak of the Han dynasty, the Tang dynasty, the Ming dynasty, and so forth, and these terms are both familiar and well understood. For the ancient period, however, the concept of a “dynasty” is much less clear, and the old convention of referring to early Chinese history as a sequence of dynasties (the Xia, Shang, and Zhou) tends to imply a much greater degree of territorial control and political centralization than appears in fact to have been the case. It is important, therefore, to be clear about the various kinds of social and political entities that existed in the Heartland Region, and the terms used to describe them, over time.

“Era” and “age” are usefully flexible terms that usually denote fairly long expanses of time, often distinguished by major political change or by technological advances. Often the two go hand-in-hand. For example, the “Bronze Age” applies to a time when a great deal of social energy was devoted to the production of metal artifacts, mostly of bronze. In the East Asian Heartland the Bronze Age began some 4,000 years ago (though pre-metallurgical working of native copper was found many centuries before that in several Heartland Neolithic cultures), coinciding with the development of early proto-states and states. The Bronze Age continued through the Shang and Zhou Periods. It began to wane during the Warring States Period (481–221 BCE) when other materials, especially iron, eclipsed the importance of bronze; it ended with the advent of China’s imperial era: that is, with the Qin and Han dynasties. (Of course, the production of bronze artifacts continued during the imperial era, but bronze had ceased by then to be the defining characteristic of the age.)

The Bronze Age itself grew out of the “stone” or “lithic” eras. The Paleolithic era was the “old stone” age, during which a fairly limited range of tools and weapons made of chipped stone were used in hunting and gathering. The Neolithic era was the “new stone” age, in which stone tools were more finely crafted and diverse in form and function, and were employed in hunting, agriculture, warfare, and as decorative or religious artifacts. The final phase of the Neolithic era in the East Asian Heartland is often known as the Jade Age, because cultures in several parts of the Heartland devoted significant human and material resources to the production of precisely crafted objects of jade, objects that seem to have served symbolic (as opposed to utilitarian) purposes.

Artifacts, whether of stone, jade, bronze, ceramic, or other materials, are sometimes recovered from ancient sites by archaeologists, who assign them to cultures on the basis of analytical investigations of their characteristics. “Culture” in this sense refers to a complex of characteristics including livelihood, settlement patterns, a suite of material objects of distinctive shape and ornamentation, and (to the extent that these things can be known), language, beliefs, and traditions. Cultures can, but do not always, evolve through stages of complexity and can, under some circumstances, give rise to civilizations (complex urban cultures) and to nations and states. We follow the common practice of anthropologists in describing four cultural steps toward civilization:

1 Simple villages, engaging in agricultural production and simple craft production, with little differentiation of social status and craft specialization, little organized warfare, little external trade, and limited contact with neighboring villages.

2 Simple chieftainships, a network of one or more towns with surrounding villages, engaged in agricultural production and some specialized craft production, with some distinctions of social rank and occupational specialization. Rudimentary government is led by non-hereditary chiefs, often claiming special military or religious authority, with the consent of a council of elders or some similar social organ. There is some organized warfare, wall-building for military defense, and some long-distance trade.

3 Complex chieftainships (nations or proto-states), encompassing a city and, often, its associated ceremonial center, several towns, and numerous villages. Agricultural production may include extensive irrigation works. Agricultural producers owe a portion of their crops to members of the ruling elite. Craft production is highly specialized. Rule, sometimes informally hereditary for several generations in succession, is monopolized by a military elite with the support of a religious elite. Warfare is common; defensive walls are massive. Residential and ceremonial buildings used by elites are large and elaborate. Ceremonials, including elite funerals, involve rare and expensive materials such as jade and metal. Trade is active and can include both specialized craft products and important raw materials. Complex chieftainships sometimes constitute nations, meaning a group of people (often united by common language, shared beliefs and traditions including supposed common descent from a founding ancestor, shared material culture, and territorial contiguity) who are conscious of themselves as a people distinct from others.

4 Highly stratified societies (civilizations, states), controlling an extensive territory with a capital city, other cities sited for strategic, ritual, or economic reasons, and numerous towns and villages. Society is complex and highly stratified, with social ranks ranging from a royal family through aristocrats, priests, craft specialists, traders, farmers, and slaves, among others. There is frequent, large-scale offensive and defensive warfare, including military action to take and hold territory. A wide range of finely produced goods is available for elite use; there is highly developed craft specialization and extensive external trade. Agricultural production is controlled by elites, and agricultural workers are in effect serfs. Rule is likely to be hereditary within a royal clan, and the term “dynasty” begins to be appropriate as a description of the political regime. A system of writing is adopted or invented.

In this book we will encounter cultures of all four stages in various parts of the East Asian Heartland Region.

Dynastic rule in the ancient East Asian Heartland Region

The mass production of bronze vessels and weapons occurred at the same time as nations or proto-states evolved into full-fledged states in the central Yellow River Valley during the late third and early second millennia BCE. According to traditional histories handed down through time for over 2,000 years, these polities were the states of Xia, Shang, and Zhou. They were ruled by “kings” (wang) who followed one another in orderly dynastic succession, frequently father-to-son but sometimes also brother-to-brother or uncle-to-nephew. These states, then, are known as dynasties for their characteristic system of hereditary monarchy within a single royal house or clan. Sometimes the Xia, Shang, and Zhou are referred to both in early texts and in modern historical writing as the “Three Dynasties” to reflect the idea of a continuous “Chinese” civilization and to emphasize the centrality and dominance of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou kingdoms within the East Asian Heartland Region. But the old idea of the Three Dynasties as isolated beacons of civilization surrounded by the territories of uncouth “barbarians” has been drastically revised by modern historical and archaeological studies, and the concept of a dynasty itself requires some qualification with respect to the Xia, Shang, and Zhou. Some scholars are reluctant (because of the absence of definitive evidence) to accept the existence of a Xia dynasty at all. The Shang dynasty undoubtedly did exist, but the extent of its territorial control is still unclear, as is the nature of its relations with its neighbors. And it is open to question whether the Zhou dynasty (conventionally dated 1045–256 BCE) can be said to have continued to exist in any meaningful way during the Spring and Autumn (722–479) and Warring States (479–221) Periods, when China became divided into a large number of quasi-independent states that at best acknowledged only the symbolic and ritual or religious authority of the Zhou kings.

The history of the state of Qin illustrates both the complexities of state formation in early China and why the term “dynasty” is problematical for the Zhou era. The Zhou kings, having replaced the Shang dynasty, established direct rule over a large territory and also extended their authority by establishing a number of aristocratic states that owed ritual fealty and military service to them. The Qin people, perhaps descendants of Qiang sheep-herding nomads (identified by some historians as “proto-Tibetan”) of the arid northwest, had organized themselves into a state within this Zhou multi-state system. This new state of Qin lay to the northwest of the Zhou royal domain in the Wei River Valley, an area that had served as the core region of the early Zhou rulers since the eleventh century BCE. Accepted as one of the many states allied with the Zhou through networks of kinship and aristocratic obligations, the Qin then began to assimilate the Zhou-style agricultural way of life, adapting to (and contributing to) Zhou-style methods of territorial administration.

In the eighth century BCE the Qin state expanded into the Wei River Valley, which had lately been overrun by another northern nomadic group, the Rong. This Rong invasion forced the Zhou kings to move their capital eastward to the Yellow River Plain in 771 BCE. In the Wei River Valley, meanwhile, the expanding Qin state evicted the Rong and reclaimed for themselves the area “within the passes” (just west of the bend in the Yellow River Valley where, after flowing southward through the Loess Highlands, it encounters the Qinling Mountains and turns east). There, making the most of the region’s important geopolitical advantages, they established a thoroughly Sinitic capital city. The Qin rulers then pursued a policy of expansion eastward and southward from their Wei River Valley stronghold, in the process becoming one of the most powerful of all the Zhou-era states, while the royal Zhou domain itself diminished to relative insignificance. At this point, the notion of a Zhou “dynasty” becomes problematical.

Eventually Qin came to dominate the entire East Asian Heartland in the late third century BCE, when they established China’s first, short-lived, imperial state (221–206 BCE). To emphasize the importance of their unification of the Heartland Region, they discarded the ancient term for the supreme ruler, wang (conventionally translated as “king”), and coined a new term, Huangdi (“emperor,” literally “brilliant l...