The origins of writing

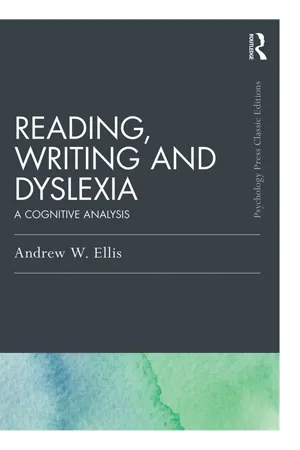

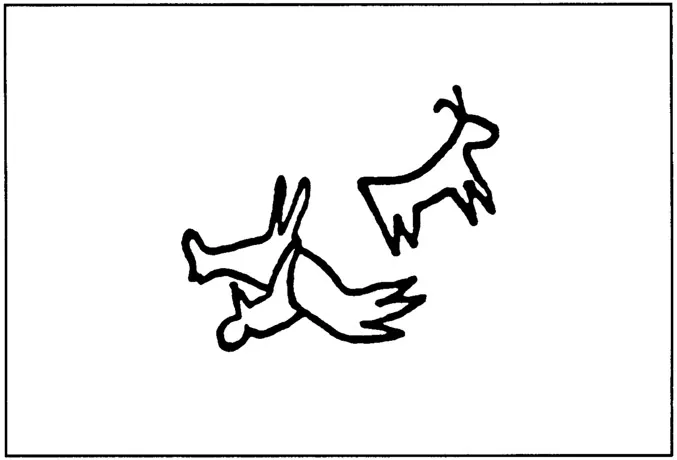

Prehistoric people used pictures to convey information, as did (or do) several more recent cultures without writing systems in North America, Central Africa, Southeastern Asia and Siberia. Figure 1.1 shows a rock drawing found near a precipitous trail in New Mexico. It warns the “reader” that, while a mountain goat (with horns) may hope to pass safely, a rider on horseback is certain to fall. “Picture writing” of this sort may be quite sophisticated in what it conveys. Figure 1.2 shows a drawing found on the face of a rock on the shore of Lake Superior in Michigan and relates the course of an Indian military expedition. The meaning of the drawing is provided by Gelb (1963, pp. 29–30). The five canoes at the top carry 51 men, represented by the vertical strokes. A chieftain called Kishkemunasee, “Kingfisher”, leads the expedition. He is represented by the bird drawn above the first canoe. The three suns under three arches show that the journey lasted 3 days. The turtle symbolises a happy landing, and the picture of a man on a horse shows that the warriors marched on quickly. The courageous spirit of the warriors is captured in the drawing of the eagle, while force and cunning are evoked in the symbols of the panther and serpent.

The interpretation of Fig. 1.2 is by no means self-evident: one needs to be a member of the culture to know, for example, that a turtle can symbolise a happy landing. Note, though, that there is no single, correct way to “read” Fig. 1.2: its meaning may be expressed many ways in English and no doubt in equally many ways in the language of the Native American who drew it. Picture writing differs from true writing in this respect – there are many ways to “read” a picture (that is, to convert its message into words), but only one way to read a sentence.

Figure 1.1 Indian rock drawing from New Mexico (from G. Mallery, Picture-writing of the American Indians. Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1893).

Figure 1.2 Indian rock drawing from Michigan (from H. R. Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Part 1, Philadelphia, 1851).

The emergence of true writing

Historical evidence suggests that picture writing of the sort just illustrated gradually became more formal and more abstract (see Diringer, 1962; Gelb, 1963). A circle, formerly used to represent the sun, could also be used to mean heat, light, day, or a god associated with the sun. Such stylised picture writing is known as “ideographic writing”. For all its formality, it remains the case that a message in ideographic writing can be “read” in a wide variety of ways. True writing systems emerged for the first time when writing symbols were used to represent words of the language rather than objects or concepts. This important step has probably been taken independently in a number of places at different times. This is not to say that picture writing has become extinct in those cultures where writing has developed: road signs and manufacturers’ symbolic instructions on household appliances are just two of the places where picture writing can still be seen today.

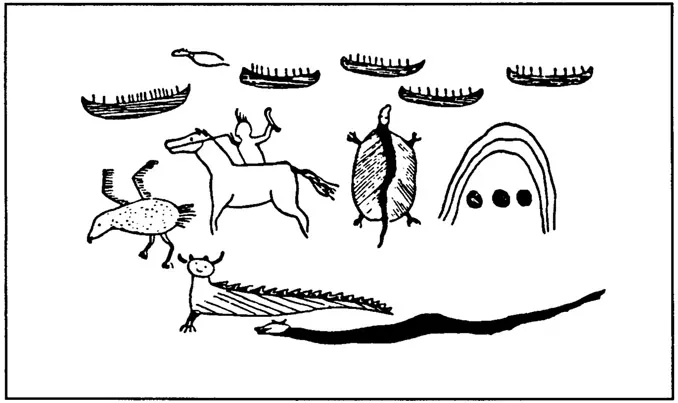

Figure 1.3 Examples of Chinese logographs.

The earliest true writing systems (such as Sumerian cuneiform writing, developed in what is now southern Iraq between 4000 and 3000 BC) were based on the one-word-one-symbol principle. Such writing systems are called “logographic” (from the Greek logos meaning word) and individual symbols are known as “logo-grams”. Modern Chinese remains logographic, as is one of the writing systems (Kanji) used in Japan (see Fig. 1.3). It is important that we should avoid equating logographic with less developed and alphabetic with more developed when thinking about writing. There are, for example, good reasons why Chinese should be written logographically. One is that the spoken Chinese language contains a great many homophones – words with different meanings which sound the same. If Chinese were written using an alphabet, these homophones would all be spelled the same, whereas a logographic writing system is able to use a visually distinct symbol for each distinct meaning. This is almost certainly of benefit to the reader of Chinese.

Many modern writing systems are, however, alphabetic; that is, they use a different letter, or a group of letters, to represent each distinctive sound in the spoken language. The first step in the development of the alphabet involved the logograms of early writing systems becoming progressively less and less picture-like. Their increasing arbitrariness may have fostered a change of attitude in readers and writers who may have come to regard logograms less as representing concepts or meanings and more as representing words in the spoken language. When this transition happens, a logogram may be used not only for its original meaning, but also to represent a homophone with a different meaning but the same sound – as if a circle meaning SUN was also used to represent the word SON or, to borrow an example from Fromkin and Rodman (1974), as if two logograms for BEE and LEAF were combined to represent the abstract word BELIEF.

This use of logograms to represent word-sounds was taken a step further when the Egyptian logographic symbols were adopted by the Phoenecians, a people who lived on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. They spoke an entirely different language from the Egyptians, but borrowed the Egyptian hieroglyphic symbols to represent the syllables of their own language. All connection between the symbols and their original meanings was now lost. In the hands of the Phoenecians, the conversion of an initially logographic writing system to a syllabic and sound-based one was completed (around 1500 BC).

The last major step towards the invention of the alphabet occurred around 1000 BC. That was when the ancient Greeks took over the syllabic Phoenecian writing system, adapting it by using a separate written character for each consonant and vowel sound of the Greek language. All modern alphabets are descendants of the Greek version (English comes from Greek via the Roman alphabet). To someone brought up with an alphabetic writing system, using letters to represent sounds may seem like a simple and obvious way to capture speech in visible form, but when thinking about reading and writing it is worth bearing in mind the fact that, as far as we know, the alphabetic principle has been invented just once in human history – by the Greeks around 1000 BC.

The origins of English spelling

In what we might call a “transparent” alphabetic writing system, the spelling of each word conveys that word’s pronunciation clearly and unambiguously. Some modern alphabets, such as Finnish and Italian, come close to being transparent in this way. English written words like DOG, SHIP and PISTOL are also transparent (or “regular”) because their pronunciation is straightforwardly predictable from their spelling to anyone who knows the normal correspondences between English letters and sounds. However, as teachers are only too well aware, many written English words deviously conceal their pronunciations. One need only contemplate the mismatch between spelling and pronunciation in such “irregular” words as YACHT, DEBT, ISLAND, WOMEN, KNIGHT and COLONEL to appreciate the truth of this.

English has not always contained the sorts of irregularly spelled words we find in today’s books. Before the Norman Conquest (AD 1066), a standard system of spellings was in use throughout the country. Regional variation in spelling later became the norm. By about AD 1400 English words were spelled as they were pronounced, varying from place to place as dialect pronunciations varied, but spellings were still all transparent when matched against local dialects.

The introduction in England of the first printing press (by William Caxton in 1476), and the subsequent rapid spread of the new technology, heralded a move back towards standardisation of spellings. Unfortunately, the transparency of English spelling was an early victim. For a start, many early printers were Dutch and did not always bother to ascertain how English speakers pronounced words. It was these printers who, for example, put the CH in YACHT (because the equivalent Dutch word contained a sound similar to that in the Scottish pronunciation of the word “loch”). Previously, the English spelling of YACHT had been YOTT.

To complicate matters further, there were at large in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries influential spelling reformers. Present-day spelling reformers typically aspire to bring English spellings back into line with their pronunciations. Earlier spelling reformers had different aims: they wanted to alter spellings in such a way as to reflect the Latin or Greek origins of words (at the expense of transparency if necessary). In their hands, the spelling of DETTE was changed to DEBT, DOUTE to DOUBT, and SUTIL to SUBTLE in order to reflect the origins of those words in the Latin words debitum, dubite and subtilis, respectively. Sometimes the reformers got it wrong. They introduced a C into SCISSORS and SCYTHE because they thought (wrongly) that both words derived from the Latin word scindere (to cleave); similarly, we owe our modern spelling of ANCHOR to a false historical link with the Greek word anchorite. Other examples of false etymology are the S in ISLAND (formerly ILAND) and the H in HOUR (formerly OURE); neither of those letters has ever formed part of the English pronunciation of those words.

The process of standardising English spellings was more or less completed by the time the first dictionaries were produced in the eighteenth century, the best known of which is Dr Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755). Dictionaries have many virtues, but they also have one major drawback. The pronunciations of words change down the years. They always have, and they always will. Spellings, in contrast, become sanctified by dictionaries and fossilised within them. In the absence of spelling reform, there is a tendency for spellings and pronunciations to gradually diverge, so that more and more spellings become “irregular”, no longer reflecting pronunciation accurately. For example, in the seventeenth century, the words KNAVE and KNIFE were both pronounced with an initial “k”, WOULD and SHOULD were pronounced with an “l”, and a sound like the “ch” in “loch”, and spelled GH, occurred in the pronunciation of RIGHT, LIGHT, BOUGHT, EIGHT and similar words. All of these words have changed their pronunciations over the last 300 years with the result that their spellings, once transparent and rational, have become irregular and apparently capricious.

This tendency for spellings and pronunciations gradually to diverge has been counterbalanced to a small degree by a converse tendency for the pronunciations of words to change to match their spellings, a process known as “spelling pronunciation”. There is, for example, a whole cluster of English words whose spelling begins with H because of an ancient Latin influence, though none of their pronunciations began with a “h” when their spellings were devised. In some the H remains unpronounced (e.g. HEIR, HONOUR, HONEST, HOUR), but in others the presence of the initial H in the spelling has caused their pronunciation to be modified (e.g. HABIT, HOSPITAL, HUMOUR and HERITAGE, none of whose pronunciations contained an “h” in the seventeenth century). Other examples of pronunciation changing to accommodate to spelling are a switch from “t” to “th” in words like ANTHEM, AUTHOR and THEATRE, and the introduction of a “t” sound in the word OFTEN, which nowadays is only rarely given its original pronunciation of “offen”.

Orthography and phonology

Phonemes and letters

Linguists refer to the writing system used by a language as its orthography and the sound structure of the language as its phonology. The different sounds that are used to distinguish words with distinct meanings are known as the phonemes of the language. A spoken language contains many different sounds, but only some of them are used to distinguish between words. The “k” sound in “keep” is slightly different from the “k” sound in “cool”, the latter being produced further back in the mouth. In Arabic, those two different k’s are used to distinguish between words with different meanings. We can say that the two k’s are different phonemes in Arabic (because they can signal differences of meaning) and Arabic has different letters for them. In English, they are two variants of the same phoneme, and are therefore represented by the same letter.

English has over 40 phonemes but has inherited only 26 letters, so letters have to be combined to represent some of the phonemes (e.g. SH, CH, TH, OO, EE). Even words with regular spellings may not have the same numbers of letters as phonemes (e.g. THROAT has six letters but only four phonemes represented by TH, R, OA and T). But in many words of English, the correspondence between spelling and sound is still more indirect. For reasons outlined above, English orthography is nowadays far from transparent, containing many irregular spelling–sound correspondences, even in some of its most common words. At first blush this might seem clearly undesirable, but some have argued that all may not be for the bad (e.g. Albrow, 1972; Sampson, 1985). At least a proportion of the deviations from transparency may be justifiable, and even beneficial.

Advantages of irregularity?

We have observed that modern Chinese benefits from being able to use a different logograph for each of its many homophones (words with different meanings but the same pronunciation). English has few logographs (&, £ and $ perhaps), but not many. It does, however, contain a surprising number of homophones (e.g. YOU–YEW, MEET–MEAT, PEAR–PAIR, IN–INN, WHICH–WITCH). If, as will be argued later, skilled readers can access the meanings of familiar words directly from their written forms, then there is a clear advantage to having distinct spellings for the different meanings of homophones. Inevitably this means that at least one member of a homophone pair is likely to have an irregular spelling. Thus, the second member of each of the homophone pairs TOO–TWO, SINE–SIGN, THREW–THROUGH and KERNEL–COLONEL has an irregular spelling.

In 1913, the Oxford philosopher Henry Bradley presented the case for English spelling, arguing that skilled readers “form direct as...