![]()

1 First Americans

The Americas were initially populated during the Pleistocene ice age, at least seventeen thousand years ago. Many descendants of America’s First Nations consider their religious traditions, that they originated in a spiritual realm connected to this world, to be sufficient knowledge for the question of earliest population. A scientific worldview, by definition of science limited to empirically demonstrable data, cannot admit spiritually revealed knowledge. Thus there may appear to be strong differences between a First Nation’s account of its earliest history and the narratives prepared by professional archaeologists and paleoanthropologists. Some Indian champions feel challenged by European-derived science, and some archaeologists defend narrow scientific explanations against any other beliefs. It is important to understand that theology and science need not conflict: an account of spiritual origins conveys religious knowledge and generally can accommodate the more limited empirically based interpretations developed by scientists.

Physical and genetic data link American Indians to Asian populations, supporting the obvious probability that humans entered North America from the nearest continental mass, Asia. From the early nineteenth century, geographers pointed to the Bering Strait, between northeastern Siberia and Alaska, as the likely route. A north polar projection map (not the common Mercator equatorial projection) or a globe will show that the Spitzbergen peninsula from northwestern Norway ends close to Baffin Land in northeastern Canada, and zoologists note that reindeer moved along routes between Norway and northeasternmost Canada, but this region was heavily glaciated during Pleistocene ice advances and has always been less hospitable to humans than the North Pacific, warmed by the Japanese Current flowing across the ocean and then north along the American coast, hosting a rich bounty of fish, sea mammals, and birds. Therefore, the North Pacific–Bering Strait region remains the most likely link between Eurasia, where modern humans gradually spread over more than a hundred thousand years, and the Americas, where no earlier forms of humans, and no apes, have been discovered. Archaeological, biological, and linguistic similarities between northeastern Asian and northwestern American sites and populations support the picture of a series of movements of small human groups from Asia into America through the Bering region.

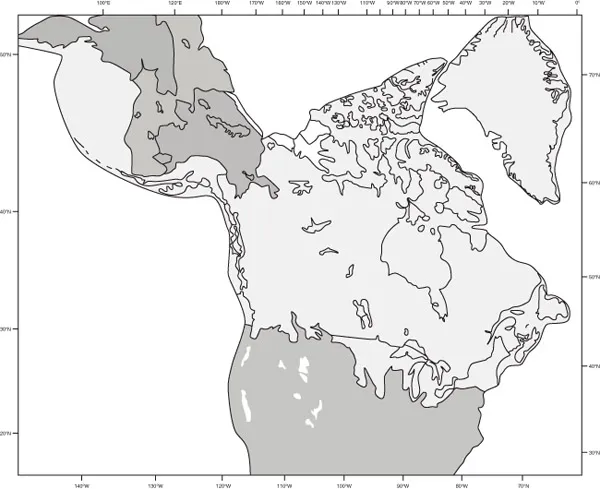

Map 1.1 Map of North American glaciation at Last Glacial Maximum, about 16,000 BCE. Light gray areas were covered by glacier ice.

Asia has had human populations for over a million years, and in the Late Pleistocene, forty thousand to ten thousand years ago, it was home to a diversity of regional groups anatomically modern in all essential characteristics (such as brain size, upright posture) but differing like contemporary populations in facial features, coloring, and average size. What we now think of as “typical Asians,” the Chinese–Japanese–Mongolian populations with high-projecting cheekbones and a fold over the nose side of the eyelid, spread over eastern Asia quite late, after some immigration into America had already taken place. Before the domination by “Mongoloids,” eastern Asia had more widespread populations resembling the historic Ainu of Japan, perhaps best described as “generalized Eurasian”—relatively light-skinned, dark hair, brown eyes, neither very tall nor very short, a range from which descendants could develop into Indo-Chinese, Polynesians, Siberians, and American Indians, as well as the stereotyped “Mongoloids.” The few skeletons found in North America dating from the end of the Pleistocene, such as Kennewick Man buried along the Columbia River, are “generalized” like this rather than showing exclusively distinctive American Indian physical characteristics.

Evidence for Early Settlement

It has been conventionally held that during much of the Late Pleistocene epoch, what is now the sea channel Bering Strait was broad land mostly covered with tundra. The Aleutian Islands lay off the southern coast of this land, called Beringia by geologists. Recent geological surveys show Beringia had massive glaciers at the maximum Pleistocene glacial periods, while its southern margins could teem with fish and sea mammals feeding on plants and microorganisms nourished by the rich flow of nutrients from glaciers’ melting edges. Climate warming since the maximum Late Pleistocene glaciations about 19,000 BCE raised sea levels as the huge ice fields, like Antarctica’s today, thawed, discharging immense floods into the oceans.

For the past five thousand years, most of Beringia has been under water. The presently existing sea channel, only a hundred miles wide, is broken by two islands (the Diomedes) in the middle, and can freeze over in the winter, so it has not been much of a barrier to human movements—historically, Alaskan Yuit and Siberian Chukchi traded and raided back and forth, with some people born on one side marrying into communities on the other. Pleistocene Beringia bridged the present continents, but its submergence did not cut off travel between them.

For years, archaeologists searched for evidence of the earliest humans in the Americas in the interior valleys of Alaska, the Yukon, and Alberta. It was assumed that mountain glaciers like those in Alaska today covered the Pacific coast during the glacial advances of the Late Pleistocene, and that an “ice-free corridor” existed along the western High Plains between the huge continental glacier centered in eastern Canada and the mountain glaciers of the Rockies and Pacific Coast Ranges. Searches found nothing older than terminal Pleistocene, 9000 BCE; for example, the Sibbald Creek campsite in Alberta on the edge of Banff National Park. Further research by geologists failed to establish any significant ice-free corridor east of the Rockies during the last Pleistocene glacial maximum. A counterhypothesis was advanced by British Columbia archaeologist Knut Fladmark, arguing that the post-Pleistocene rise in sea level that flooded much of Beringia also flooded the ancient Pacific coast, leaving late-Pleistocene (indeed, up to 3000 BCE) sites on the coastal plains now under water on the continental shelf. Fladmark, of course, could not produce site features or artifacts from these possible locations presently covered by seafloor muck and water.

Migration into North America by boats around the North Pacific, including coastal Beringia, came to seem more reasonable as geologists confirmed that northern Beringia had been glaciated and that the “land bridge” was rugged, not a flat tundra plain. From about 17,000 to 9500 BCE, sea conditions favored abundant growth of kelp, a large seaweed, offshore in the Pacific, from Japan eastward around the North Pacific and along the American Pacific coasts all the way to southern South America (with a break in the tropics from Baja California to Ecuador). Kelp grows like forests underwater, furnishing nutritious edible leaves and sheltering fish and shellfish, which, in turn, are food for larger fish and sea mammals. Families in large hide-covered frame boats like the Inuit umiak could have paddled with the current southward from the Aleutians, fishing, harvesting shellfish, hunting sea and land game, and filling out nutritional needs with berries, tubers, roots, and fruits near the shores. Kelp itself is popular in Japan (as kombo) and China as a dried snack and for flavoring soups and dishes. Early migrations into North America primarily along the coast make sense, although near impossible to document with discoveries of Pleistocene campsites or boats.

Figure 1.1 Paleoamericans butchering a mammoth at a Chesrow artifacts site in southeastern Wisconsin, 11,500 BCE, when the continental glacier ice front loomed a mile high only seventy miles north of them.

Sites that do testify to Late Pleistocene humans in North America include Nenana in Alaska, Paisley Caves in Oregon, Buttermilk Creek in central Texas, and butchered mammoths with artifacts labeled Chesrow in southeastern Wisconsin. Paisley Caves are so dry that human feces were preserved and radiocarbon dated, proving humans were relieving themselves there 12,400 BCE. All these sites date somewhat older than Clovis, for many years believed to be the earliest evidence of humans in North America, at 11,200 BCE. More interesting, the stone and bone artifacts in these and other sites dated earlier than Clovis differ from the famous long, thin, handsome Clovis spear points, and differ among the sites. It seems that at least several migrations came into North America, settling over the continent, then adopting the Clovis-style spear point created somewhere here, perhaps in the Southwest. Alternately, some archaeologists suggest, Clovis represents a population that moved over the continent, with its distinctive spear point. Almost no Clovis artifacts sites have any human remains that could indicate genetic identifications, so there are no data to indicate an associated distinctive population; the only Clovis DNA recovered is from a small child buried with Clovis blades in southern Montana. The little boy was definitely from an ancestral American Indian population, related to Siberians, and closer to Central and South American Indians than to those historically living on the Northern Plains of North America, indicating their ancestors came there later than Clovis.

The most controversial claims come from South America, and thus concern this book only peripherally. Pedra Furada, against a cliff face in interior northeast Brazil, has crude fractured stones and lenses of charcoal said to date thirty-three thousand years ago, but this material looks like it eroded from the plateau edge down into a chimney-shaped cleft in the cliff. At the base of the cliff, excavations revealed a panel of little figures painted in red on the rock; these have been dated at about 9000 BCE by association with apparent occupation material below the panel, more feasible evidence for terminal Pleistocene habitation in northern South America. Other sites, in Ecuador, Venezuela, and Peru, are dated around 13,000 to 10,700 BCE, filling out evidence for populating the Americas.

Monte Verde site in Chile was excavated by American archaeologist Tom Dillehay. Situated in a pleasant creek valley, the site evidenced wooden slabs possibly from huts, scraps of mastodon hide that may have covered the wooden hut frames, and simple but serviceable bone and stone artifacts, dated to 12,800 BCE. (The dating was based on radiocarbon, here calibrated with other measures of terminal Pleistocene age [Fiedel 1999].) Abundance of plant and animal remains preserved in the peat bog that the site became gives a detailed picture of the seeds, berries, tubers, and animal parts people used at the site. A delegation of prominent archaeologists examined the site in 1997 with Dillehay after his report on the work was completed and, although some had been skeptical, they agreed after the visit and laboratory inspection that Dillehay’s work seemed scientifically sound. Subsequently, close examination of the published report fomented renewed debate over dating of the few diagnostic artifacts and Dillehay’s interpretation of wood as hut planks. Such intense protracted debate typifies reports of humans in the Americas earlier than the 11,000 BCE “Clovis horizon,” the oldest thoroughly documented archaeological evidence in the continent (Waters and Stafford 2007).

The most practical route from Asia to Chile would have been along the Pacific coast. Postulating sailing during the Pleistocene from Australia across the immense South Pacific to Chile would be a wild card. Unlike protohistoric Polynesians who used highly sophisticated navigational skills and watercraft to sail across the Pacific, Pleistocene humans probably lacked sails on their rafts and canoes. That no evidence has been found of settlements on the mid-Pacific Polynesian islands before Polynesian colonizations beginning in the second millennium BCE argues against any likelihood of earlier crossings of the vast ocean. With the general consensus that Dillehay’s Monte Verde was the oldest professionally excavated, definitely human occupation site in the Americas, Fladmark’s circum-North Pacific route gained credence.

Accepting Monte Verde as an authentic human settlement more than twelve thousand years ago in southernmost South America upset conventional archaeology on two counts: (1) that humans had come into the Americas earlier than the dates for the Clovis finds, 11,200 BCE, and (2) that these earlier people made artifacts less distinctive than the Clovis stone blades. In effect, Monte Verde opened the door to a raggle-taggle crowd of contenders for first-comers: it had been simple to declare that the first-comers were virtuoso flintknappers (knap, “to break with a snap,” as in chipping flint) leaving signature masterfully chipped stone blades at their sites; now archaeologists had to consider sites with nondescript artifacts like those at Monte Verde. Geological context and chronometry (methods of dating) would be more critical than ever in evaluating possibly early sites, and these can be tricky. For example, a child’s skeleton found in a Pleistocene layer in a cliff face in southern Alberta turned out to have been buried by pushing it into a cleft in the cliff, which then filled up with soil, practically obliterating the cleft. Radiocarbon dating indicated that the child is a few thousand years old, closer to us than to the Pleistocene. Radiocarbon dating itself runs into odd effects just at the end of the Pleistocene due to strong and relatively rapid fluctuations in global climate when the glaciers released incredible floods of their meltwater, changing evaporation rates and thereby the amounts of radioactive carbon rising into the air. Increased cosmic ray penetration of the atmosphere at this time of extraordinary global changes may also have added unusual amounts of radioactive carbon to the air. Organisms at this time probably breathed in more of the carbon isotope, leaving a greater amount in their bodies when they died, and so more when the amount was measured millennia later. Paleoindian material can be as much as two thousand years older than the radiocarbon count indicates, and to further confuse researchers, materials from each side of the climate flip-flop can give the same measure although they may have existed a thousand years apart.

Clovis and Other Mammoth Hunters

Finding butchered mammoth remains securely identifies a Paleoindian site—the animals became extinct in North America about 11,000 BCE. The type site at Clovis, New Mexico; Blackwater Draw in northwestern Texas at Lubbock; and the Murray Springs, Naco, and Lehner sites in Arizona were among the first excavated to establish the association of Clovis stone blades with slaughtered mammoths. Butchered mammoths with nondescript stone tools, such as the two in southeastern Wisconsin, clearly belong in the Paleoindian period, confirmed by radiocarbon dates and geological context. Archaeologists cannot tell whether the butchers’ artifact tradition did not favor the Clovis style, or instead it merely happened that the butchers’ Clovis blades were taken along to the next camp, or not fallen in the excavated sections of the sites.

Clovis style is remarkable for its beautiful stone blades, frequently made on pleasingly colored, fine crystalline material quarried in blocks that often were carried hundreds of kilometers to ensure the quality of Clovis artifacts. To manufacture the blades, artisans first struck large flakes off the blocks, using the sharp flakes for everyday cutting and scraping tasks, and then with exquisite control struck long ribbon-like flakes across the faces of the formed blade to thin it evenly. Finally, the hallmark of the Clovis style was produced, an oval channel running up the face of the blade from its base: the “fluting.” Fluted bases uniquely mark Clovis and the similar but later and shorter Folsom-style blades. Clovis is associated with mammoths and Folsom with large extinct species of bison. The fluting channel was expedient for hafting the blade to its shaft in a tongue-and-groove manner. Unfluted but still exquisitely ribbon-flaked stone blades continued the Fluted Tradition technique into the early Holocene, to around 8000 BCE.

All known Paleoindian habitation sites seem to have been camps, generally on ridges where people could watch for game animals coming to streams or marsh edges; in addition to mammoths, mastodons, musk-oxen, horses, camels, bears, antelopes, deer, and small game were killed. Paleoindians could live surprisingly close to the margins of the great glaciers, because nutrient-rich meltwaters supported rich grazing for mammoths and other prey for hunters. Archaeology indicates communities were composed of a few families, moving at least several times a year. Small campfires with broken or worn-out stone and bone tools indicate household activity areas, probably in or beside tents or wigwam-type dwellings. Stacks of butchered game bones suggest storage caches of meat; other cache clusters contain complete or partially finished stone artifacts and sometimes red ochre.

Essentially, Paleoindians were, in global terms, Late Paleolithic people, fully modern anatomically but without agriculture and permanent villages. They lived by hunting, exhibiting high skill in manufacturing weapons and in strategies for moving into range to use their spears, either propelled by hand throw or with the added leverage of the atlatl (spear-thrower board) or thrust directly into the animal. Changing camps to follow game movements and harvest plant foods in season, their habitation sites look meager. Their nomadic life was well adapted not only to surviving on the abundant game of the Late Pleistocene, but also to adjusting to the tremendous shifts in climate and environments of the terminal Pleistocene. The period’s stone and bone artifacts found throughout North America prove migrants’ remarkable capacity to enter and exploit new habitat zones, filling the continent with human families.

The Early People

Human skeletons from early Holocene times are few, with fewer so far definitely dated to the Pleistocene. The most complete skeleton is known as Kennewick Man, from the discovery locality on the lower Columbia River (near Richland, Washington). From Kennewick Man’s nearly entire skeleton, found eroding out of the riverbank, and his physical characteristics differing from some common among today’s American Indians of the region, it was initially concluded that he was a historic Euroamerican immigrant. Then the archaeologist noticed a stone spear point embedded in his hip! Radiocarbon dating revealed he lived about 6500 BCE (Chatters 2000; Chatters et al. 2014). He was taller than general for Plateau Indians, with a long rather than broad face, altogether somewhat resembling in build the Ainu of northern Japan. Because the Ainu are believed to represent an Asian population pushed into their northern island refuge by expanding, more typical Mongoloid Asians, quite possibly as late as the historic era, it is hardly surprising that a northwest American man resembles people directly across the North Pacific. The Ainu, incidentally, were accustomed from ancient times to using boats and fishing, consistent with the Pacific coastal route for movements into America from Asia. What is important to realize about Kennewick Man is that analysis of his genetics shows that although he, like other American Indians, was distantly related to Asians, he is American Indian and could be an ancestor of present-day First Nations of the Columbia River valley. Compared to the Montana child buried with the Clovis artifacts, Kennewick Man’s genetics also show affinities with Central and South American Indians, but a stronger relationship to northern North American Indian populations. Extended comparisons of Kennewick M...