This is a test

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

North Sámi: An Essential Grammar is the most up-to-date work on North Sámi grammar to be published in English.

The book provides:

-

- a clear and comprehensive overview of modern Sámi grammar including examples drawn from authentic texts of various genres.

-

- a systematic order of topics beginning with the alphabet and phonology, continuing with nominal and verbal morphology and syntax, and concluding with more advanced topics such as discourse particles, complex sentences, and word formation.

-

- full explanations of the grammatical terminology for the benefit of readers without a background in linguistics.

Suitable for linguists, as well as independent and classroom-based students, North Sámi: An Essential Grammar is an accessible but thorough introduction to the essential morphology and syntax of modern North Sámi, the largest of the Sámi languages.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access North Sámi by Lily Kahn, Riitta-Liisa Valijärvi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Sámi within the Uralic language family

Sámi is a member of the Uralic language family. The Uralic family consists of two main branches. One is Samoyedic, which includes a number of languages spoken in Siberia, and the other is Finno-Ugric, which includes languages spoken to the west of the Ural Mountains. The Uralic languages are spoken by approximately 25 million people in total in a broad geographical area stretching from Siberia to the Atlantic coast of Norway. The Uralic languages with the largest numbers of speakers are Hungarian (approximately 14 million speakers), Finnish (5.4 million speakers), and Estonian (1.2 million speakers). These three languages are the only members of the Uralic family with official national status in an independent country; in addition, they are official languages of the European Union. Certain other Uralic languages with relatively large numbers of speakers, such as Mordvin (Erzya and Moksha), Mari, Udmurt, Komi, and Karelian, have official status in various regions of Russia. There are also a number of highly endangered Uralic languages, such as Selkup and Nenets in Siberia and Veps and Votic by the Baltic Sea.

As a typical Uralic language, Sámi has a rich morphological and derivational system, including seven nominal cases, four verbal moods, a negative verb, a variety of postpositions, possessive suffixes, and an extensive array of derivative suffixes for both nouns and verbs. In addition to these core grammatical features, the basic Sámi lexicon is of Uralic stock. For example, the verb ‘to go’ is mannat in North Sámi, mennä in Finnish, and menni in Hungarian; the noun ‘fish’ is guolli in North Sámi, kala in Finnish, and hal in Hungarian; and the noun ‘blood’ is varra in North Sámi, veri in Finnish, and vér in Hungarian. As it is spoken in the periphery of the Uralic geographical area, Sámi has retained some original Uralic features that have been lost in many other Uralic languages, such as the dual form of pronouns and verbs.

Sámi belongs to the Finno-Ugric branch of the Uralic family. It is generally assumed to be most closely related to the Fennic subgroup of languages, which includes Finnish, Estonian, and Karelian. It is debatable whether the similarities between Sámi and Fennic are due to historical relatedness or are contact-induced. Sámi differs from its supposed closest relatives in that its vowel system has undergone radical changes, it possesses a rich inventory of consonants not found in Fennic languages, and it has a considerably smaller number of cases.

1.2 Sámi language variants

Sámi is not a single unified language but rather comprises nine distinct living linguistic varieties as well as two extinct ones. All of these varieties can be traced back to a reconstructed proto-Sámi language which is assumed to have originated in what is now southern Finland approximately 2,500 years ago, from where they spread into northern Fenno-Scandia over the course of subsequent centuries. The distinct Sámi language varieties are believed to have emerged in approximately 800 CE. However, there is a hypothesis that one of the varieties, South Sámi, may have diverged earlier, based on its archaic case suffixes and more complicated vowel system than the other Sámi varieties. The Sámi language varieties all reflect early contact with speakers of Baltic and Germanic (particularly Nordic) languages, as well as proto-Fennic in the form of loanwords.

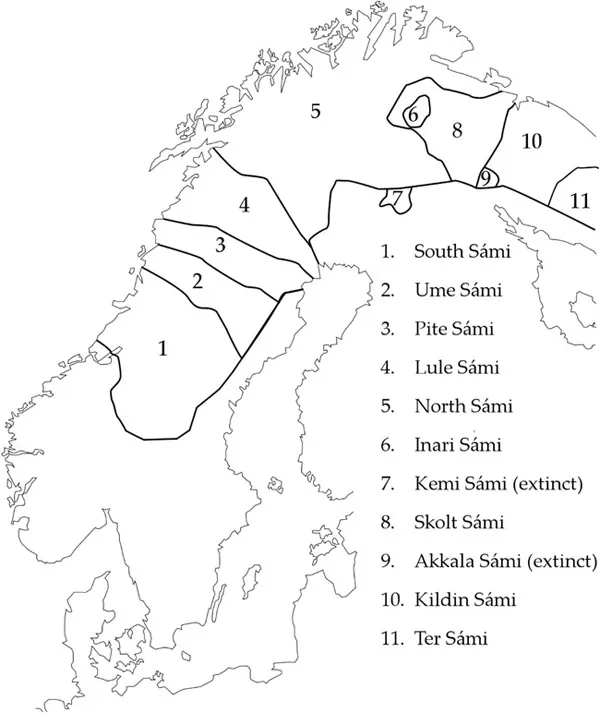

These varieties are spoken in the region known as Sápmi, which stretches from central Scandinavia in the southwest to the Kola Peninsula in the northeast, in territory belonging to present-day Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. The majority of Sámi speakers live in Norway. The Sámi language varieties form a continuum in which those forms spoken next to each other are usually mutually intelligible, whereas speakers of more geographically distant varieties cannot communicate with each other. Overall, the degree of difference between the Sámi language varieties can be compared to that of the Romance or Scandinavian languages. The Sámi linguistic varieties can be divided into two main groups, Western and Eastern. The Western Sámi varieties can be further divided into two subgroups, South (South and Ume Sámi) and Central (Pite, Lule, and North Sámi). The Eastern Sámi varieties can similarly be divided into two subgroups, Mainland (Inari, Kemi, Skolt, and Akkala Sámi) and Peninsular (Kildin and Ter Sámi) (see map 1.1).

Sami Map 1.1 Sámi-speaking regions

There is significant variation in speaker numbers among the nine Sámi language varieties: North Sámi has by far the largest number of speakers, whereas other varieties, such as Pite and Ter Sámi, are extremely endangered. Kemi Sámi became extinct in the nineteenth century, while the last known speaker of Akkala Sámi died in 2003. The Sámi language varieties and their approximate numbers of speakers are shown here.

Sámi language variety | Approximate number of speakers |

|---|---|

South Sámi | 600 |

Ume Sámi | 20 |

Pite Sámi | 20 |

Lule Sámi | 1,000–2,000 |

North Sámi | 20,000 |

Inari Sámi | 300 |

Kemi Sámi | extinct |

Skolt Sámi | 420 |

Akkala Sámi | extinct |

Kildin Sámi | 500 |

Ter Sámi | 2–10 |

The largest six Sámi varieties, namely South Sámi, Lule Sámi, North Sámi, Inari Sámi, Skolt Sámi, and Kildin Sámi, all have an established literary standard with a distinct orthography. In addition, an official orthography was launched for Ume Sámi in 2016, and an orthography for Pite Sámi has recently been established as well. Some of these language varieties have a relatively long literary tradition. For example, an ABC and Mass book in South/Ume Sámi was published in 1619. This was the first book published in any Sámi language variety. Written North Sámi dates to the seventeenth century as well (see section 1.3.2 for details). The current South Sámi, Lule Sámi, North Sámi, Inari Sámi, and Skolt Sámi orthographies are all based on the Roman alphabet, with the addition of a number of special characters. By contrast, Kildin Sámi uses an extended version of the Cyrillic alphabet.

The Sámi language varieties spoken in Norway, Sweden, and Finland all have a degree of official recognition in those countries. In Norway, the Constitution guarantees the right of the Sámi people to preserve and develop their language, and moreover the Sámi Language Act of 1990 made Sámi an official language of six northern counties. In Sweden, Sámi became an officially recognised minority language in 2000. Moreover, a law concerning national minorities from 2009 guarantees Sámi speakers the right to receive care for children and the elderly in Sámi and states that the language can be used when dealing with the authorities in a number of municipalities. In Norway and Sweden, these laws do not specify any particular varieties of Sámi, and most resources are spent on North Sámi, which has the greatest number of speakers. In Finland, the Sámi Language Act of 1992 and the revised version of 2002 guarantee children the right to study Sámi in school and guarantee Sámi speakers the right to use Sámi in all government services in certain municipalities. This act refers specifically to three particular language varieties, North Sámi, Inari Sámi, and Skolt Sámi. In Russia, Sámi has no official status, and the Sámi language varieties spoken there receive little or no government support.

The following table provides a sample of the eight Sámi language varieties with an independent orthography while giving an indication of the resemblances and differences between them.

‘bird’ | ‘I come’ | |

|---|---|---|

South Sámi | ledtie | boatam |

Lule Sámi | lådde | boadáv |

North Sámi | loddi | boad̄án |

Inari Sámi | lodde | poad̄ám |

Skolt Sámi | lå’dd | puäd̄ám |

Kildin Sámi | ло’нд | поадам |

Ume Sámi | låddie | bådáv |

Pite Sámi | lådde | bådav |

1.3 Historical and sociolinguistic introduction to North Sámi

1.3.1 Early history of North Sámi

North Sámi has long been spoken above the Arctic Circle in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. However, very little is known about the history of the language before the earliest written attestations.

1.3.2 Written North Sámi

Written records of North Sámi are relatively late, beginning with missionary activity in the seventeenth century. The first book in North Sámi is a collection of prayers and confessions published in 1638 (first edition) and 1640 (second edition) entitled Swenske och lappeske ABC-book ‘Swedish and Lappish ABC Book’. This was followed by Manuale Lapponicum (published in 1648), written by the priest Johan Tornaeus (early 1600s–1691). This seminal volume contained a number of religious texts written in a language based primarily on Swedish varieties of North Sámi.

The North Sámi language itself began to attract scholarly attention in the same period. The first grammar of North Sámi was written by the Norwegian priest and linguist Knut Leem (1696/1697–1774) and published in 1748, and the first dictionaries were published in 1756 and 1768. A contemporary of Knut Leem was Anders Porsanger (1735–80). He was the first Sámi to receive higher education, assisted Leem in his research, and translated portions of the Bible into North Sámi. Unfortunately, most of his work has now been lost. In the same period, the Swedish priest Per Fjellström (1697–1764) attempted to create a common orthography for all the Sámi language varieties spoken in Sweden. This variety was based primarily on South Sámi but incorporated elements of North Sámi and was used in Sweden throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In the 1820s the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask (1787–1842) devised an orthographic system for North Sámi which included for the first time the use of special consonants to denote sounds particular to the language. His work, which was published in 1832, was based on Leem’s grammar. Rask collaborated with the Norwegian priest Nils Vibe Stockfleth (1787–1866), and the latter put the system into use in a range of North Sámi publications, including Luther’s Small Catechism (published in 1837), the New Testament (published in 1840), a grammar (published in 1840), a Norwegian–North Sámi dictionary (published in 1851), and Luther’s Postil (published in 1857). Stockfleth also translated parts of the Old Testament.

However, the first complete North Sámi Bible translation was not published until 1895. A significant role in this translation was p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Phonology and orthography

- Chapter 3 Nouns

- Chapter 4 Adjectives

- Chapter 5 Pronouns

- Chapter 6 Numerals

- Chapter 7 Verbs

- Chapter 8 Adverbs

- Chapter 9 Adpositions

- Chapter 10 Conjunctions

- Chapter 11 Particles

- Chapter 12 Clauses

- Chapter 13 Word formation

- Suggested resources

- Index