This is a test

- 110 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

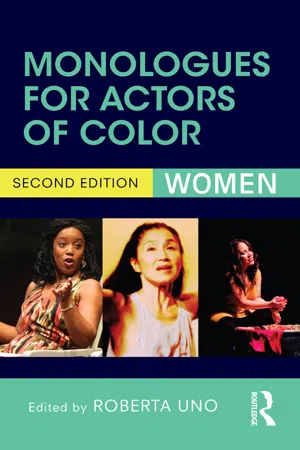

Actors of colour need the best speeches to demonstrate their skills and hone their craft. Roberta Uno has carefully selected monologues that represent African-American, Native American, Latino, and Asian-American identities. Each monologue comes with an introduction and notes on the characters and stage directions to set the scene for the actor.

This new edition now includes more of the most exciting and accomplished playwrights to have emerged over the 15 years since the Monologues for Actors of Color books were first published, from new, cutting edge talent to Pulitzer winners.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Monologues for Actors of Color by Roberta Uno in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Théâtre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

after all the terrible things I do

From “Closing Shift” (Scene 3). An independent bookstore in an average-sized, unremarkable Midwestern town. Now.Linda, late 40s, Filipina, is a typical American immigrant and the owner of Books to the Sky, an independent bookstore. She has recently hired Daniel, a young, aspiring novelist who has just graduated from college. The pair forms an intimate bond when they discover that bullying has played a significant and painful role in both their pasts. But their kinship ends when Linda discovers that Daniel was not a victim of bullying like her dead son but a bully himself.In this monologue, Linda names Daniel for the coward he is while confronting her own role in her son’s tragic end.

LINDA: I KNOW WHAT YOU ARE! We both know what we are! I KILLED MY SON! I KILLED MY SON!!!

When Isaac learned what those words on his locker meant—faggot, queer, homo—he said to me, “They’re not bad words, mommy. They’re words for boys who want to kiss boys.”

And I said, “It doesn’t matter. No one should call you that.”

And then Isaac said to me, “But I do want to kiss boys, mommy.”

And I smacked him.

I smacked him so hard I couldn’t send him to school the next day.

I forgot I could be that angry until the night in the store with you.

I told him he should never say that again and certainly never, ever do it.

Isaac grew. He would tell me someone at school ruined his things or hurt him, and instead of telling him everything was alright, I told him he should stop wearing that shirt or walking like that or talking so much and so fast and so gay. And I would make him speak to me with his hands at his sides, so he wouldn’t wave them around. And I would make him deepen his voice. And I would tell him to stop being friends with those girls and not to be seen with that boy.

But it didn’t stop. And after every horrible incident all I ever said was, “What did you do? Who were you with? What did you say?”

And then he took his own life.

And do you know what the first emotion I felt was? Relief. It wasn’t all I felt or even most of it. But it was the first thing. I wouldn’t have to raise a gay son. We would never fight about what I wanted for him. He would never leave his family for a man.

And it was actually hard for me, at first, to hate his bullies. To not think that that’s what happens to gay people, as though he should have expected this.

Then two years later my husband left me for not being as destroyed as he was. And I left the church—I couldn’t go back, I don’t know why. And then ten years after I smacked my nine year old son simply because he trusted me, all of that anger faded away, and I looked around, and I was alone. No son. No husband. No family. Just this store. And I have tried never to get that angry again.

But then you told me about that boy who trusted you. Who you betrayed so completely that all he could do was…what Isaac did. You were the person who should have loved him the most, but you couldn’t, so how could he love himself? And I knew what I was.

I taught Isaac how little he was worth. All he did was act on what I taught him, taking that first smack to its inevitable conclusion. I killed him.

You aren’t who I want you to be, and I want to kill you for it. That night I felt helpless, and my instinct was to hurt you like I hurt my son.

See? I know what I am. So do you. We’re cowards.

Aftermath

Outside of Iraq, 2008.Basima, an Iraqi refugee and young mother (late 20s–30s) addresses the audience directly as she tells the story of the bombing that decimated her family.

BASIMA: I gave birth in July. Our first child. And when he was two months old, it came time for us to get him vaccinations. (long beat) So—we were on the way to the doctor’s with the baby. Everyone came in the car, me and my husband and my mother and my son and my sister—because my sister was just seventeen, we couldn’t leave her alone in the house, someone, the militias…could come into the house and…(beat. she can’t say it. finally):…and hurt her.

In the car, we were all just happy with the baby and fussing, would this vaccination go okay, would he cry, would he feel better.

And then, all of a sudden—ya3ni, sound, and heat, lots of heat. And, the smell of burnt hair and flesh. And pain. The car shook, hard, and right away I lost my sight.

I don’t know how I got out of the car. I couldn’t see. The thing I could hear most was the sound of my husband’s voice. I just followed the sound back to him.

He wanted to get out of the car but his legs were fused to the seat. I tried to get him out, but he was heavy, I couldn’t I couldn’t. I felt the fire start to eat at my hands. I tried to get him out, I tried, but I couldn’t. (beat) So I left. I called for whoever could help me. I was yelling at the top of my lungs. But there wasn’t any person, there wasn’t anybody. It was as if the world had ended.

And then another explosion, and screaming and yelling. And then my husband’s voice disappears.

I hear bullets from every direction. And I’m barefoot, and I can’t see and I don’t know what to do so I just sit down. There’s nobody there. Nobody nobody. It is as if Baghdad has been emptied of people.

Of course, you know, this accident was on Al Jazeera. They showed me like—my blouse was open. My clothes were burned off. And I’m asking, what happened, where’s my husband, my son, my mother, my sister. One Muslim guy, do you know what he says to me? He says (clearly mocking) “They went to Allah.”

From 10:30 till 12:30 I was in the street. After two hours I heard the blades of a helicopter. Americans came, they were speaking English. They were checking out what the explosion was. It was a long time till they came to me. I was secondary. But whatever I can say about the accident wouldn’t be enough. (to translator) Translate this, okay, so that they can…(she needs a break).

Another Part of the House

Act 2, two months after Act 1, at the end of a long afternoon in Bernarda Alba’s bedroom, in a modest farmhouse in Santa Clara, in the province of Las Villas, Cuba, 1895.In this re-imagining of Garcia-Lorca’s La Casa de Bernarda Alba, Bernarda, 60, the pious matriarch of the Alba family, has just been told by Poncia, the family maid, that her daughters fear her more than love her. She blames her mother’s wildness, and her dead husband, Antonio’s licentiousness for the sexual inappropriateness and ungodliness of their daughters.Here, she tells his portrait what she really thinks of him in a rare, honest moment alone.

BERNARDA: I have to do something about my mother. She’s pulling my house down into the grave with her. I won’t have it. Not again. (Bernada crosses to the portrait of her recently dead husband, Don Antonio and speaks to it.) I—never loved you, Antonio. That was my secret. But you knew it. I endured every child—every child a female. A torture. Because I knew what I had to teach them and give them so that they could turn out better than I ever could. A boy would have been so much easier. You can ignore them. But girls have to be trained to keep their legs together. Without the training they become whores or servants or worse—poor. So poor that they can’t stop begging for everything they get. Only begging keeps those kinds of girls alive. No one in this family will ever beg. And that’s my doing, husband. Mine! Where were you in this? Where were you ever? I wish I could cry for your dead soul, but I can’t Antonio. For the first time in many years, I can finally hear myself speak. Because your desire isn’t drowning me, filling every pore in my skin with wetness. Being alone now is like a desert, and I feed on that sand that keeps you out of me. Stay away, Antonio. I’ll wear black forever if you’ll just stay away—from me and from my daughters. Everything you taught them could kill them. I have to undo you from us all. (Bernarda takes down Don Antonio’s portrait and exits with it under her arm.) Maybe I’ll bury you.

Becoming Cuba

Act 1, scene 2. A pharmacy in Havana, Cuba, 1898.Hatuey’s Wife is ageless and the color of rebellion.Hatuey was the great Taino warrior who led the first resistance against the Spanish Conquistadors in the Caribbean. We know his wife was also a great leader, but we don’t know very much else about her. In the play Becoming Cuba, Hatuey’s Wife makes an unscheduled appearance. She talks directly to the audience, and although characters onstage feel her, they don’t know she’s there. She is part of the spirit world that walks the island of Cuba—those people lost in the many battles to conquer and re-conquer the land.

HATUEY’S WIFE: (She is dressed in traditional Taino garb, and speaks like a warrior queen, by way of Union City.)

To understand me, you have to remember me.

Let me rest in a corner of your mind, as I was, dressed in leather and flowers, a Taino queen. A warrior. A mother.

One of The First Nation.

Everyone says that I was enamored of the men who landed that day. That the lust of Hatuey’s Wife was insatiable. That I thought the men with yellow hair and silver skin were gods.

Seriously? Have you white people looked at yourselves? Have you been to a beach lately? White people are so ugly. For real! Like they’re radioactive. All skin peeling off and hair plastered to their faces by the sweat. Why do you sweat so much? Skinny, anemic looking, all pasty and pale.

Gods? What kind of god gets a sunburn?

No, I wasn’t thinking they were beautiful. I knew they were men. I’m not stupid. Deformed men, under all the armor. I thought they must be hideous to cover themselves like that. We have a man like that, and we never let him out of the cave where he lives. The sight of his body is offensive. I thought the white men were like him. Maybe they had been cast off from their land of beautiful brown people—too many of them to keep tied up, so the queen sent them away in this spaceship, over the ocean.

I felt sorry for them. Hatuey’s Wife. Soft in the heart and in the head.

I invited them to dinner. Cooked up a big vat of frijoles. 200 partridges on a spit. Wild boar. Yuca and maduros. Chile and lime juice. They came, they ate. And then they killed us. Yeah. I know. For real. While it was happening, I thought, this is the worst party ever.

Butterfly

A dim sum restaurant in London. The present.Mui Foong is in her thirties and originally from Hong Kong. She has renamed herself Butterfly, after the Puccini opera. She was married to a British man but is now divorced, and struggling to meet men while working as a waitress in a dim sum restaurant. It must be said that Butterfly doesn’t entirely understand the world around her, but is doing her very best to make sense of it. Although she has lived in London for more than ten years, her English is still imperfect. When her boss at the restaurant asks her to emcee an event, she is naturally thrilled to take her moment in the limelight, which she also sees as an opportunity to practice her speaking skills. She then gets somewhat carried away, and ends up telling the audience more about her love life than is strictly appropriate.

BUTTERFLY (MUI FOONG): This is fun, talking to you like this. Helps me practice my English. You don’t mind, do you? At home I have only my cat to talk to,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Permissions

- The monologues