eBook - ePub

LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care

Empowering Approaches for an Inclusive System of Care

This is a test

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Representing an often overlooked population in social work literature, this book explores the experiences of LGBTQ youth as they navigate the child welfare system. Adam McCormick examines the entirety of a youth's experience, from referral into care and challenges to obtaining permanency to aging out or leaving care. Included throughout the book are stories from LGBTQ youth that address personal issues such as abuse, bullying and harassment, and double standards. Filled with resources to foster resilience and empower youth, this book is ideal for professionals who are hoping to create a more inclusive and affirming system of care for LGBTQ youth.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care by Adam McCormick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

LGBTQ YOUTH IN CARE

Overlooked and Underestimated

Jason

Jason was referred to the foster care system when he was just 11 years old. Jason’s referral was unique because unlike most other child welfare cases, the state did not come in and take Jason away from his biological family. There was no suspected history of any type of physical or sexual abuse. In fact, up until that point in time, Jason had never experienced any form of neglect or abuse. Part of what makes Jason’s case so unique is not even that he was one of the few children in care whose family members contacted children’s protective services and requested that they take custody of Jason Although it is rare, child welfare professionals do receive requests from a child’s immediate caretakers to intervene and take custody of the child from time to time. The reasons for these referrals usually occur when a child’s caretaker feels that they are unable to provide adequate care to a child or when a child has emotional and behavioral concerns that exceed the capacity of their caretakers. Jason’s case was unique because it did not involve any of these dynamics. In fact, when his grandmother was asked by a child protective services investigator why she would no longer care for him, she simply stated that he just didn’t fit in with her family and that she refused to allow him to stay in her home any longer. She never expressed any concerns about his behaviors being too much for herself and her husband to handle. Jason never exhibited any emotional or behavioral challenges beyond what was developmentally appropriate for an 11-year old. Both she and her husband were still committed to caring for Jason’s younger siblings; therefore, there were no concerns about their ability to provide care.

Jason would eventually go into foster care at the request of his grandparents. Over the course of the next five years, he would have seven different placements, some in traditional foster family homes and some in group homes, and at each one a request would be made for Jason to be removed. He never exhibited any of the risky behaviors that are often exhibited by kids who experience numerous placement breakdowns. He was never suspended from school, never initiated a physical confrontation, and never reported any suicidal or homicidal ideations. In fact, he recalls that most of the time when he would ask why he was being moved, his caseworkers would simply attribute it to his inability to fit in.

By the time he was approaching his 16th birthday, Jason had finally established some stability in a group home for teenage boys. After living in this placement for nearly a year, Jason sat his group home parents down one evening and told them that he was gay. Jason described the moments leading up to this encounter as one of the scariest experiences of his life. He would later describe the overall experience as one of the most empowering and liberating experiences that he would ever have. Jason’s group home parents responded with an enormous sense of sensitivity and affirmation. They praised Jason for his courage and assured him that they would do everything that they could to make sure that his experiences would be no different than any of the other boys in the home.

On the heels of this empowering experience, Jason would approach the Director of his group, a gentleman who Jason had developed a very close relationship with, and he would again come out. Jason would not experience the same affirmation and sensitivity this time. In fact, the Director immediately told Jason how disappointed he was in Jason. He would go on to tell Jason that being gay was an abomination and inconsistent with the values of the faith-based foster care agency that supervised Jason’s group home. The Director would discourage Jason from mentioning this to anyone else and was very clear that if he mentioned this “gay phase” to anyone else, he would risk losing his placement. Jason went several weeks without telling anyone about this encounter. He would eventually confide in a school counselor about the interaction with the Director. The school counselor, with the best of intentions, phoned the group home Director to voice some of the concerns that she had with his response to Jason’s coming out. A few days later, Jason arrived at his group home after school to find his caseworker sitting on the front porch with all of his belongings packed tightly into a duffle bag. He would learn that the Director of the group home had submitted an emergency request for his removal. The Director cited Jason’s inability to respect the values of the agency as the reason for his removal. Over the course of the next three years, Jason would bounce from placement to placement, living in group homes, foster homes, and emergency shelters, until he eventually aged out of care on his 18th birthday. He was admitted into a transitional living program and would begin a new journey navigating the system as a homeless young adult.

Jason’s story was chosen to provide an introduction into the experiences of LGBTQ youth in the child welfare due in large part to the numerous themes present in his experience that many LGBTQ youth experience as they navigate the child welfare system. From his pathway into care, his experiences while in foster care, to his exit from the system, Jason’s story sheds light on the many challenges the child welfare system has in its capacity to provide safe, affirming, and accepting care to LGBTQ youth.

Until recent years, little attention has been given to the experiences of LGBTQ youth who come into contact with the child welfare system. Historically, child welfare practitioners, policy makers, and foster parents have failed to recognize the presence of LGBTQ youth on their caseloads and in foster homes. Recent efforts aimed at exploring the experiences of LGBTQ youth who come into contact with the child welfare system suggest that a number of barriers and challenges exist in creating a safe and affirming environment for LGBTQ youth.

Overrepresentation of LGBTQ Youth in the Child Welfare System

It is estimated that LGBTQ youth are disproportionately overrepresented in the foster care system; however, the exact number of LGBTQ youth in the system is unknown (Mallon, 2006). In a recent study of youth in the California foster care system, 13.6% of foster youth identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning and 13.2% reported some level of same-sex attraction. Furthermore, in this same study, 5.6% of respondents identified as transgender (Wilson, Cooper, Kastanis, & Nezhad, 2014).

The reasons that so many LGBTQ youth come into contact with child welfare professionals might often seem unrelated to sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression (SOGIE); however, upon closer examination, these reasons usually have a great deal to do with a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity (Mallon, 2011). While the child welfare system is designed to assure safety and security for children and youth who are at the risk of experiencing further maltreatment, the experiences of LGBTQ youth in care are often saturated with further maltreatment, discrimination, and marginalization. Similarly, little emphasis is placed on issues of permanency-related services for LGBTQ youth, such as family reunification, adoption, and legal guardianship. LGBTQ youth are significantly more likely to age out of foster care than straight youth; thus, their transition into adulthood is often faced with numerous challenges and barriers.

The following chapters will provide further insight into the experiences of LGBTQ youth who come into contact with the child welfare system. The stories and experiences of many LGBTQ youth will be shared in an attempt to help put a face on a population that has largely been overlooked and underestimated. After interviewing numerous LGBTQ youth and young adults who have navigated the child welfare system, the author has concluded that this is a population that has an enormous sense of resilience and resourcefulness. Furthermore, the author firmly believes that providing a voice for individuals like Jason and many other LGBTQ youth is an effective mechanism for better understanding the challenges and barriers that exist in creating an affirming and inclusive child welfare system for all children and youth.

Language and Terminology

The words and terminology that are used when working with LGBTQ youth in care can have a profound impact on their sense of comfort and safety. Given the fact that many LGBGT youth have had previous negative experiences around issues related to their sexual orientation or gender identity, they are often looking for signs or indications from child welfare professionals and caretakers that are sensitive and affirming. The use of language that is competent and sensitive can create a more inclusive culture in which LGBTQ youth can be themselves. The remainder of the chapter seeks to provide some basic terminology and language for child welfare professionals and caretakers to possess to enhance and strengthen their interactions with LGBTQ youth.

SOGIE

SOGIE is an acronym that stands for sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. When working with youth in the child welfare system, it’s important to remember that all youth have a SOGIE, and much like race and ethnicity, a youth’s SOGIE is an important piece of their identity.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation is the desire for intimate emotional and/or physical relationships with another person. The terms heterosexual and homosexual were historically used in referring to an individual’s sexual orientation; however, those terms are largely discouraged because they reduce a youth’s identity to purely sexual terms. When discussing issues related to a youth’s sexual orientation, child welfare professionals also want to avoid using the term sexual preference. This type of language suggests that being gay is somehow a choice and can be changed or modified in some way. Terms such as gay, lesbian, and bisexual are much affirming and sensitive to use when discussing a youth’s sexual orientation.

As families and society become more accepting of LGBTQ individuals, the average age for youth to come out as gay, lesbian, or bisexual has dropped significantly. In the 1980s, the average coming out age was 22 as compared to today where the average coming out age is 16. According to a recent Pew survey, the average age at which LGBTQ individuals first noticed that they were something other than straight was around 12 years.

Gender Identity and Expression

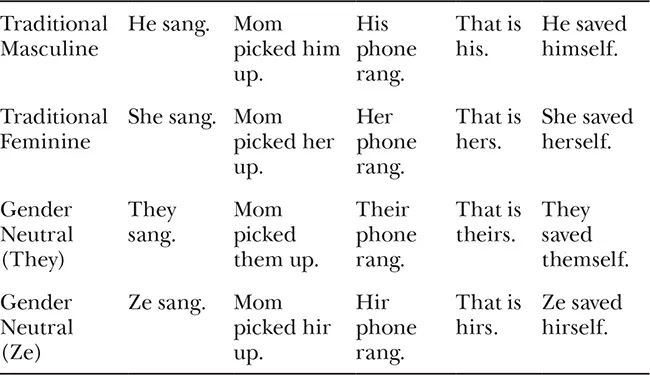

A person’s gender identity can be viewed as their internal sense of being masculine or feminine. The term transgender is often used as an umbrella term for individuals whose gender identity (internal sense of gender) is different from their assigned gender. When working with transgender youth, child welfare professionals should always seek to use a transgender youth’s chosen name and chosen use of pronouns consistent with the gender they identify with. In cases where a youth uses certain pronouns when referring to themselves, it is important that child welfare professionals mirror that language to the best of their ability. Furthermore, making it a habit to ask youth what their preferred pronouns are can be effective in modeling respect and cultural competence. When youth are referred to with the wrong pronouns, they may feel disrespected, aligned, or dismissed. LGBTQ youth often have a heightened vigilance when meeting new professionals, and the use of gender-preferred pronouns can potentially provide them some ease. Some common gender-neutral pronouns that child welfare professionals might consider include the following (Table 1.1):

-

They/Them/Theirs—This is certainly the most commonly used gender-neutral pronoun and can be used in both the singular and plural.

-

Ze/hir—Ze is pronounced like “zee” and is used to replace he/she/they. Hir is pronounced like “here” and replaces her/hers/him/his/they/theirs.

Table 1.1 Gender-Inclusive Pronoun Chart

Cisgender is a term that is used to describe someone whose gender identity largely aligns with those typically assigned to their assigned gender. Gender conforming is a reference for individuals who do not behave in a way that conforms to the traditional expectations of their assigned gender. More simply put, gender nonconforming is a term that many individuals prefer when their gender identity and expression do not fit neatly into any one category.

Some youth do not identify as gender binary, a concept describing gender identity as being entirely masculine or feminine. A youth who identifies as gender variant likely does not conform to the societal constructs or expectations related to gender. Some gender-variant youth might identify as genderqueer, in which they don’t identify as either male or female, but rather a combination of the two genders.

The terminology and concepts related to SOGIE are very fluid and consistently evolving. Many child welfare professionals may feel overwhelmed or confused by the fluidity of these concepts and terms. LGBTQ youth in the child welfare system often feel a sense of frustration with the lack of willingness of child welfare professionals to address and acknowledge issues related to SOGIE. In many cases, LGBTQ youth feel that this reluctance to address issues stems from the discomfort and lack of confidence that child welfare professionals might have when it comes to discussing issues related to SOGIE (McCormick, Schmidt, & Terrazas, 2016). While keeping up with the most sensitive and affirming terminology and language is crucial, it is equally important that child welfare professionals not allow their discomfort or lack of confidence to prevent them from engaging in crucial conversations about a youth’s SOGIE. The experiences of LGBTQ youth who navigate the child welfare system provide evidence of the profound negative impact that silence and a lack of acknowledgement can have on their well-being and permanence. In situations where a child welfare professional might lack the necessary knowledge or vocabulary related to a youth’s SOGIE, it’s important that they remember that it is okay to ask questions.

2

PATHWAYS INTO FOSTER CARE FOR LGBTQ YOUTH

Overrepresentation of LGBTQ Youth

It is unknown just how many LGBTQ youth currently reside in the foster care system. Data assessing a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity are not tracked by child welfare agencies. Similarly, many youth in care are reluctant to disclose information about their sexual orientation or gender identity for a number of reasons. Many LGBTQ youth fear that their placements could be in jeopardy or that they may be discriminated against or marginalized if their caretakers were to become aware of their LGBTQ status. Thus, many youth feel that remaining in the closet is safer than being out in their current foster homes. While it is understandable that an LGBTQ youth would opt to not disclose certain information as a way to protect themself as they navigate the foster care experience, it is a dynamic that should be very concerning for child welfare professionals.

Recent efforts to assess the benefits of being out suggest that youth who are out to their caretakers have significantly higher rates of self-esteem and life satisfaction than those who are not. Similarly, LGBTQ youth who come out to their loved ones or caretakers are much less likely to be depressed (Russell, Toomey, Ryan, & Diaz, 2014). Furthermore, we have known for some time that teens who are forced to keep their identities a secret are at an increased risk of depression, suicidal ideation, risky sexual behaviors, and suicidal behaviors (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanches, 2009). Many LGBTQ youth in care go to incredible lengths to keep their identities a secret.

Jennifer

Jennifer described the immense amount of energy and planning that she devoted to keeping her identity a secret from her longtime foster parents: “From the time I woke up in the morning until the time that I went to bed I would do everything that I could to make sure that they wouldn’t know. I would delete texts, pretend that I had boyfriends, and make sure that none of my teachers knew anything because X (foster mom) emailed my teachers everyday. It’s a lot more work than what you would imagine.”

Jennifer described the immense amount of energy and planning that she devoted to keeping her identity a secret from her longtime foster parents: “From the time I woke up in the morning until the time that I went to bed I would do everything that I could to make sure that they wouldn’t know. I would delete texts, pretend that I had boyfriends, and make sure that none of my teachers knew anything because X (foster mom) emailed my teachers everyday. It’s a lot more work than what you would imagine.”

In a recent survey of youth aged 12–21 in the California foster care system, 19.1% of respondents identified as LGBTQ (Wilson, Cooper, Kastanis, & Nezhad, 2014). In this same study, nearly a quarter (22.2%) of respondents aged 17–21 identified as LGBTQ. Therefore, the rate of LGBTQ youth living in foster care is nearly twice the rate of LGBTQ youth in the general population.

Many LGBTQ youth enter the child welfare system for the same reasons as straight youth. There are, however, a number of explanations that help us to better understand why so many LGBTQ youth end up in the foster care system. The experiences of LGBTQ youth who come into contact with the child welfare system often differ significantly from the experiences of straight youth. The reasons that an LGBTQ youth is referred to the child welfare system often look much different from those of straight youth. Although at first glance they might seem like they have nothing to do with a youth’s SOGIE, after f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1 LGBTQ Youth in Care: Overlooked and Underestimated

- 2 Pathways Into Foster Care for LGBTQ Youth

- 3 Experiences in Care for LGBTQ Youth

- 4 Permanency Challenges for LGBTQ Youth

- 5 Foster Family Acceptance

- 6 Trauma-Informed Care and LGBTQ Youth in Care

- 7 Recommendations for Practice

- Article Reviews

- Sexual and Gender Minority Disproportionality and Disparities in Child Welfare: A Population-Based Study

- Functional Outcomes Among Sexual Minority Youth Emancipating from the Child Welfare System

- Foster Family Acceptance: Understanding the Role of Foster Family Acceptance in the Lives of LGBTQ Foster Youth

- References

- Index