This is a test

- 194 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The unique beauty of the Japanese garden stems from its spirituality and rich symbolism, yet most discussions on this kind of garden rarely provide more than a superficial overview. This book takes a thorough look at the process of designing a Japanese garden, placing it in a historical and philosophical context.

Goto and Naka, both academic experts in Japanese garden history and design, explore:

-

- The themes and usage of the Japanese garden

-

- Common garden types such as tea and Zen gardens

-

- Key maintenance techniques and issues.

Featuring beautiful, full-colour images and a glossary of essential Japanese terms, this book will dramatically transform your understanding of the Japanese garden as a cultural treasure.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Japanese Gardens by Seiko Goto, Takahiro Naka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Planificación urbana y paisajismo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The Japanese garden is one of many garden styles in the world. But what is a Japanese garden? Is it a garden constructed in Japan, one designed by a Japanese person, or one composed of rocks, stone lanterns, and stepping stones? None of these criteria are adequate for defining a Japanese garden, which is best described as a garden with unique symbolism and objectives that developed within a distinctive climate and culture, and that possesses a unique spatial structure serving those objectives.

In general, gardens throughout the world can be classified as geometric or naturalistic. Islamic, Italian, and French gardens are geometric, and English, Chinese, and Japanese gardens are naturalistic. However, the Japanese garden differs from other naturalistic gardens in its symbolism and objectives, which developed over its 2,000-year history. We call such a naturalistic garden whose symbolism and form developed in accordance with Japanese traditional aesthetics a “Japanese garden.” Therefore, understanding the Japanese garden means understanding the meanings it embodies and the objectives it fulfills.

Japanese gardens may look similar, but they are classified into different categories based on their metaphoric themes, and layout and relationship to architecture. There are four main categories of metaphorical themes in the Japanese garden: awareness of the power of nature, Buddhist teaching, literature, and the tea ceremony.

The power of nature is a major theme not only in Japanese gardens but in all genres of Japanese art because of Japan’s geographical location. Most Japanese islands are within the Asian monsoon region. During the summer, the temperature, humidity, and amount of sunlight can reach tropical levels. In addition, summer monsoons bring abundant rainfall, which allows for the production of life-sustaining rice. Rice cultivation is well suited to countries with high rainfall because it requires ample water; however, during the summer monsoons, rainfall is so irregular that it is not uncommon for a harvest to be poor due to drought or flooding. For this reason, from an early period in Japanese history, rituals developed to pray to gods for rain in the spring and for a good harvest in the autumn. Reflecting this role of prayer and ritual, the Japanese garden is a space in which elements such as rocks, plants, streams, and ponds represent gods.

Between the relatively long and comfortable autumn and spring, the winter is cold, and many regions in Japan have heavy snowfall. These distinctive four seasons became a time frame for agriculture and life itself that formed Japanese culture and aesthetics. For example, Japanese residential architecture, unlike Western, is not completely enclosed but designed to introduce nature so seasonal changes can be observed from within the living space. The Japanese aesthetic is unique in appreciating plants not only for their form and color but also as indicators of the change of seasons. The Japanese consider nature a changing phenomenon and appreciate seasonal change as an integral aspect of its beauty. Japan is possibly the only country in the world whose poetry and literature could not survive without the theme of the four seasons.

The ancient Japanese, whose lives depended upon countless natural phenomena, did not conceive of a single deity, as in monotheism. Instead they considered all natural elements, such as mountains, oceans, the sun, and the wind, as gods, the so-called “eight million gods in the world.”

They revered and thanked these natural elements and energies, and prayed that the spirits of the gods would be peaceful and not cause catastrophes.

In the tradition of Shinto, the Japanese native religion, purified places where the spirits of the gods were believed to gather were called niwa, which means “garden.” In Shinto shrines we can still often find a huge rock, god’s seat (iwakura), or a huge tree, god’s tree (goshinboku). This worship of rocks and trees in Shinto shrines reflects the basic attitude of nature worship and finding spirituality in natural elements that are the distinguishing features of the Japanese garden in contrast to Chinese and English gardens.

The second theme of the Japanese garden is its adoption of features from other cultures, such as those of China and India, particularly Buddhism. The history of the Japanese garden can be said to have begun back in the Jōmon period, roughly from 14,000 BCE to 300 BCE, for there is evidence in ruins of stones being arranged for ritual purposes. A man-made landscape of streams with cobblestones was found in the Jonokoshi Ruins from the Kofun period (250–538 CE). Although the Japanese did not have written documents before the fifth century, since these streams and rocks were constructed at some distance from houses, it seems likely that the landscape was built for a special occasion, probably the worship of nature. If a space made from natural elements for observation and contemplation and not practical use can be called a garden, then these landscapes were early Japanese gardens, constructed before the introduction of Chinese culture.

Such gardens for nature worship were developed into larger-scale residential gardens with the influx of Chinese culture during the Asuka period (538–710 CE). Since Japan is a natural fortress because it is completely surrounded by the ocean, it had never experienced an invasion until the Mongols attacked during the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE). The ancient Japanese believed that only good things came from beyond the ocean. Innocent of invasion, they were extremely receptive to foreign cultures and introduced positive aspects of them with great respect. Many foreign cultures, not only Korean and Chinese but also Indian and other Southeast Asian cultures, were introduced to Japan via the Silk Road during this period. Buddhism, Confucianism, Chinese literature, and ink brush paintings were some of the cultural elements adopted in Japan. The capital city of Nara was designed according to the plan of a Chinese city, and Chinese-style gardens with a large pond built using stone blocks were constructed in the guesthouses where important delegates from China stayed.

In the Nara period (710–794 CE) many new elements from the Asian continent, including Mahayana Buddhism from India and Taoism from China, were introduced into Japanese gardens. Since Mahayana Buddhism was mixed with Taoist thought in China, Taoist elements were introduced into Japan as part of Buddhism. In the Heian period (794–1185 CE) the first garden style for a Buddhist temple, the paradise garden, made for Pure Land (Jōdo) school temples, was established to visually represent the Buddha’s world. In the following Kamakura period, Zen gardens emerged to express Zen philosophy. Although the philosophy of Zen (Chán Buddhism) was introduced from China, the Zen garden was originally designed in Japan. Generally, these Japanese Buddhist gardens were formed combining Buddhist cosmology, the Taoist idea of paradise, and Shinto nature worship. One of the distinguishing characteristics of the Japanese garden is this reflection of multiple religious beliefs. The paradise garden and Zen garden styles were successful, and continue to be applied to new gardens in the temples of these sects to the present day.

The third theme of the Japanese garden is its representation of the natural scenery that appears in classical Japanese literature. From the ancient period, Japanese poems often used famous scenic places as their theme. These scenic places are called meisho (famous place), and some meisho, such as Ama-no-hashidate, Matsushima, and Itsukushima, are well known from poems by famous poets. Following this tradition, the Japanese garden also often had meisho as its main theme. This attitude toward designing gardens to recreate the scenery of a particular landscape is similar to that reflected in English picturesque gardens. However, English picturesque gardens were designed based on landscape paintings, while Japanese gardens were designed based on actual sites. Moreover, although the picturesque garden is a realistic representation of a landscape painting, the Japanese garden becomes a metaphor for the scenery through names and suggestive forms. In other words, even if the actual site is an infinitely long allée of old pine trees, a Japanese garden might represent this landscape with just a few small pines. Such miniaturization is also one of the distinctive characteristics of the Japanese garden. In addition to miniaturization, the elements of a Japanese garden often have a double meaning (mitate) to suggest a story or philosophy with the given scenery. Using this mitate method, the Japanese garden can deal with any theme of unlimited scale in an extremely limited space, creating a place that can be visited throughout the year without boredom.

The last theme of the Japanese garden is the tea ceremony, a unique culture developed during the Muromachi period (1392–1573 BCE). The tea garden is an entryway to the tea house, which could be built within a larger garden but was independent from other parts of the garden and residence. What the tea garden symbolizes is not so much a religious concept or literature, but the awareness of nature.

The design layout of the Japanese garden can generally be classified into three types: 1. the landscape garden, which has hills and a pond; 2. the dry garden, which represents natural scenery without water; and 3. the tea garden, which provides an approach to a tea house. Furthermore, the Japanese garden can be classified into six types according to its function and relationship to architecture: 1. the residential garden; 2. the paradise garden; 3. the Zen garden; 4. the tea garden; 5. the stroll garden; and 6. the Westernized garden.

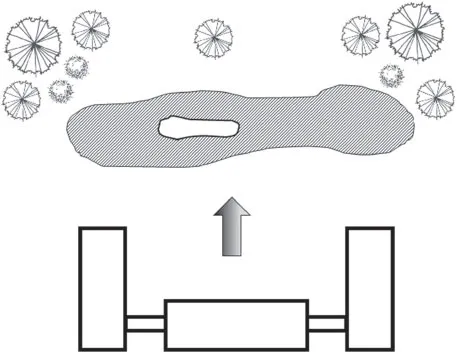

Figure 1.1 Main view in a palace-style garden

The first type of Japanese garden is the residential garden for noble houses, the so-called shinden-zukuri palace-style garden, designed not only for viewing but also for entertainment, boating, or ceremonies such as poem parties (Figure 1.1). This garden was planned mainly to be viewed from one side of the building.

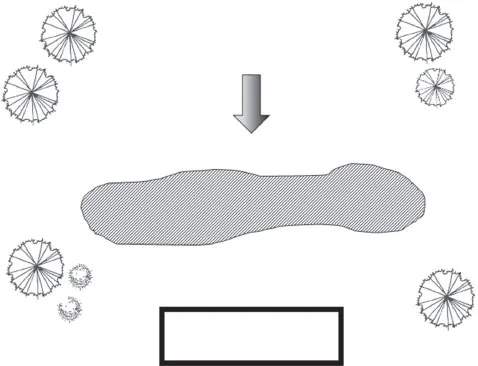

The second is the paradise garden, which was developed as the idea of the Pure Land spread among aristocrats. The purpose of the paradise garden is to visualize the Pure Land. A major example is Byōdo-in’s paradise garden, which was designed with the temple housing the Buddha statue as its focal point (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Main view in a Pure Land garden

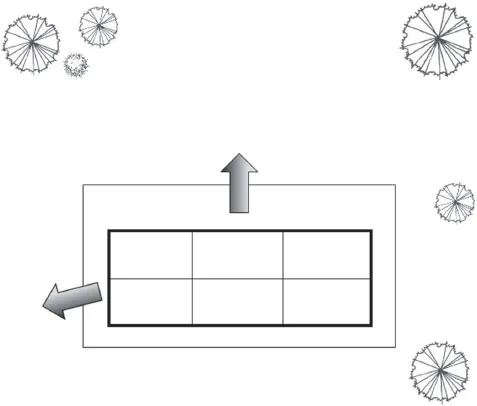

Figure 1.3 Main views in a Zen garden

The third type of garden is the Zen garden for meditation, which was developed in the Kamakura period, when political power shifted from the nobility to the military and Zen Buddhism became popular. Gardens for the highest status Zen monks’ residences, called hōjō, were generally on flat ground around the building (Figure 1.3). Zen monks set rocks on this flat ground and created dry gardens. With the introduction of square columns, not the round ones found in palace-style buildings, the hōjō building could have sliding doors which separated the view of the garden from the interior space. Furthermore, an attached veranda ran around the building, from which gardens on all four sides could be viewed, or they could be viewed from within the building. Unlike the palace-style garden, the Zen garden was intended for observation only, not for activities. The scenery of the Zen garden is not meant to present a visual image of Buddha’s world, but to reflect the abstract cosmology or goals of Zen, which could be interpreted in infinite ways.

The fourth type of Japanese garden, by use, is the tea garden, built for the tea house, which emerged during the Muromachi period when the tea ceremony was established. The tea garden is a small passage to the tea house, designed to let visitors forget about the outside world and mentally prepare for the tea ceremony within a few short steps (Figure 1.4). Because the tea house is the minimum size necessary to perform the tea ceremony, the tea garden is an extremely small space with stepping stones, a water basin, stone lanterns, a bench, and a toilet. Visitors prepare for entry to the tea house using these garden elements as part of “the way of tea.” Unlike the Zen garden, which is designed only for viewing, the tea garden is a space for visitors to use and move through.

The fifth type of Japanese garden is the large-scale garden for strolling, the so-called daimyō garden or stroll garden, built by feudal lords (daimyō) mainly in the Tokyo area during the long, peaceful Edo period (1603–1868 CE). These gardens have a large pond at the center and many sceneries created for visitors to walk through (Figure 1.5). The main purpose of these gardens is leisure, and they reflect a variety of themes; for example, Confucian thoughts in Koishikawa Kōraku-en and classic literature in Katsura Imperial Villa.

Figure 1.4 Relationship between the tea house and garden

The sixth type of Japanese garden was designed with Western influence during the Meiji period (1868–1912 CE), a time of rapid modernization and Westernization. The new style of Japanese garden designed during this period dispensed with classic Japanese symbolism in rocks and plants, and represented a visual image of the Japanese landscape without miniaturization. The main purpose of this type of garden was the enjoyment of natural scenery without metaphoric themes.

Japanese gardens express different themes in different layouts and different relationships to architecture. Various styles and usages of the Japanese garden developed through different periods in Japan’s history. However, unlike the eighteenth-century English picturesque garden, which did not incorporate elements of the geometric-style garden developed in the previous century, new styles of Japanese garden embraced earlier styles. Moreover, the old styles were never repudiated when a new style emerged, and so were passed on to the next generation. For example, themes such as the Turtle Island and Buddha’s Mountain, or meisho such as Ama-no-hashidate, which were developed during the tenth century, were found in the st...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Themes

- Chapter 3 Landform

- Chapter 4 Garden elements

- Chapter 5 Maintenance of the Japanese garden’s symbolism

- Chapter 6 Symbolism of the Japanese garden explained in historic garden manuals

- Chapter 7 Symbolism of the Japanese garden in North America

- Chapter 8 Symbolism of the Japanese garden: A conclusion

- Appendix 1: Twenty outstanding Japanese gardens, selected by the authors

- Appendix 2: Key words

- Appendix 3: Addresses of gardens in figures

- Appendix 4: Bibliography

- Appendix 5: Credits

- Index