- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Police Photography

About this book

Quality photographs of evidence can communicate details about crime scenes that otherwise may go unnoticed, making skilled forensic photographers invaluable assets to modern police departments. For those seeking a current and concise guide to the skills necessary in forensic photography, Police Photography , Seventh Edition, provides both introductory and more advanced information about the techniques of police documentation. Completely updated to include information about the latest equipment and techniques recommended for high-quality digital forensic photography, this new edition thoroughly describes the techniques necessary for documenting a range of crime scenes and types of evidence, including homicides, arson, and vehicle incidents. With additional coverage of topics beyond crime scenes, such as surveillance and identification photography, Police Photography , Seventh Edition is an important resource for students and professionals alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Police Photographer

Contents

| Introduction |

| Police Photography: A Short History |

| The Many Uses of Photography in Police Work |

| Public Relations |

| Police Photography and Fire Investigation |

| Evidential Photographs |

| Legal Considerations |

| The Future of Photography |

| References |

ABSTRACT

Police have been using photography to document and capture details about crimes for many decades. Generally the courts have upheld the use of photographic images as evidence at trial. Phe most widely used system of photography in today's law enforcement community is the digital camera. Digital cameras pose new methods and better technology than traditional film systems to assist police in their duties.

Key Terms

- Bertillon system

- Digital imaging

- Digital-single-lena-reflex (DSLR)

- Eastman Kodak.

- Florida v. Victor Reyes

- Green v. County of Denver

- Luco v. United States

- People v. Jennings

- Photomacrography

- Photomicrography

- Polaroid

- Reddin v. Gates

- State v. Thorp

- Will West-William West Case

Introduction

During a routine patrol of a suburban neighborhood, Officer Black receives a call instructing him to investigate a two-car collision a few blocks away. He drives to the scene and, before leaving his patrol car, he notes that, although one of the vehicles has sustained severe damage, no one seems to be injured.

The drivers of the two cars are arguing heatedly (neither driver, Officer Black observes, seems to have been clearly in the wrong), and nearby a passenger is sobbing. Officer Black ensures no one is injured, calms the drivers, soothes the passenger, records each person's description of the accident (there were no witnesses outside the two cars involved), and radios for a tow truck to remove the damaged vehicle. Before the tow truck arrives and the automobiles are moved, he takes a few measurements, sketches the scene, reaches into his pocket and takes out his cell phone, and snaps four photographs of the accident.

In addition to being a calmer of nerves, an investigator, a law enforcer, an impartial witness (although after the fact), an artist, and an agent for the immediate conclusion of a minor catastrophe in the lives of three people, Officer Black is a police photographer. That is not his job description, but neither is his role as a street psychologist. He may never use PhotoShop or hold a digital single-lens reflex camera in his hands. But his function as a police photographer is every bit as important as that of the head of the crime laboratory in his department who takes photographs in his spare time that could vie with the best of those seen in National Geographic.

Both Officer Black and the head of his department's crime laboratory are police photographers; this book is for both of them.

Police Photography: A Short History

Photography is most obviously useful in police work when photographs serve as evidence that may prove invaluable to investigators, attorneys, judges, witnesses, juries, and defendants. Often, a good photograph can be the deciding factor in a conviction or acquittal when no other form of real evidence is available.

Photographs were used in court as early as the mid-1800s. In 1859, a photograph was used in the case of Luco v. United States (64 U.S. (23 HOW.) 515.16 L.Ed. 545 [1859]) to prove that a document of title for a land grant was, in fact, a forgery. The first recorded use of accident photography was in 1875: "Plaintiff, in a horse and buggy, was injured when, in attempting to go around a mud hole in the center of a road he drove off an unguarded embankment" (Blair v. Inhabitants of Pelham, 118 Mass 420 [1875]). The photograph was admitted in evidence to assist the jury in understanding the case. Two years later, photographs were admitted as evidence in a civil suit involving a train wreck (Lock v. The Souix City & P.R.R., 46 Iowa 210 [1879]).

Although neither of these early photographs used in evidence was taken by a police photographer, the use of photography in police work is well established in the early annals of photography. In 1841, 18 years before Luco v. United States, the French police were making daguerreotypes (an early form of photograph) of known criminals for purposes of identification.

One of the first cases to hold that a relevant photograph of an injured person was admissible in evidence was Redden v. Gates in 1879 (52 Iowa 210, 1879). The photograph was a tintype, a photograph made on a thin iron plate by the collodion process. It showed whip marks on the plaintiff's back 3 days after the assault. In 1907, in Denver, Colorado, all intoxicated persons were photographed at the police station.

Speeding motorists were being detected with photographic speed recorders by 1910. The state of Massachusetts approved the use of such devices and gave a full description of their operation. Although radar is a more popular device for this operation today there has been a resurgence in the use of photo-enforced traffic laws and devices in the past decade.

The use of fingerprint photographs for identification purposes was approved in 1911 in People v. Jennings (96 N.E. 1077, 252 Ill. 534, 1911), although 1882 was the year in which fingerprints were first officially used for identification purposes in the United States. Gilbert Thompson of the US Geological Survey in New Mexico used his own fingerprint on commissary orders to prevent their forgery. In 1902, New York Civil Service began fingerprinting applicants to discourage the criminal element from entering civil service, and also to prevent applicants from having better-qualified persons take the test for them.

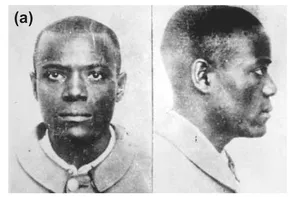

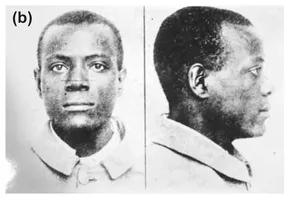

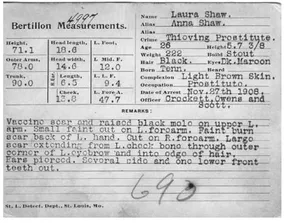

The famous Will West case took place at Leavenworth Prison in 1903. When he was received at Leavenworth, Will West denied ever having been imprisoned there before. Clerks at the prison insisted that West had been there and ran the Bertillon instrument (used for identification purposes) over him to verify measurements. When the clerk referred to the formula derived from West's measurements, they were practically identical, and the photograph appeared to be that of Will West. When the clerk turned over the William West record card, he found that it was that of a man already serving a life sentence for murder. Subsequently the fingerprints of Will West and William West were compared. The patterns bore no resemblance. The fallibility of three systems of personal identification (photographs, Bertillon measurements, and names) was demonstrated by this one case. The value of fingerprints as a means of identification was established. There was a great similarity in the photographs of Will West and William West (Figure 1.1). An officer must be careful when identifying a person from a photograph. After the Will West-William West case, most police departments began using photographs, Bertillon measurements, and fingerprints on their "mug shot" files. Eventually, the Bertillon system was discarded (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.1

The Wilt West-William West case demonstrated that photographs and Bertillon measurements of persons were not accurate methods for identification. Will West (a) and William West (b).

The Wilt West-William West case demonstrated that photographs and Bertillon measurements of persons were not accurate methods for identification. Will West (a) and William West (b).

One of the early uses of firearms identification is recorded in a 1902 case, Commonwealth v. Best (62 N.E. 748, 180 Mass. 492, 1902). Photographs of bullets taken from the body of a murdered man were put into evidence, along with a photograph of a test bullet pushed through the defendant's rifle. This method of obtaining a test bullet is not proper, according to modern authorities, but the use made of the comparison photographs was to be followed in many later firearms identification cases.

Before the modern electronic flash units of today, photoflash bulbs were used and readily accepted by the public by 1930. Before the photoflash bulbs, people used flash powders—dangerous explosives that produced a great deal of objectionable smoke. The photoflash bulb was a revolutionary development that made possible the taking of many evidence pictures that were otherwise unobtainable. Undoubtedly, their use contributed greatly to the development of police photography.

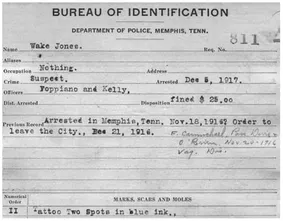

FIGURE 1.2

Early mug-shot files depicted photographs, fingerprints, and Bertillon measurements. Eventually, Bertiilon measurements were discarded as a means for identification. Courtesy Memphis Police Department.

Early mug-shot files depicted photographs, fingerprints, and Bertillon measurements. Eventually, Bertiilon measurements were discarded as a means for identification. Courtesy Memphis Police Department.

Ultraviolet photography was approved in a decision handed down in the 1934 case of State v. Thorp (171 A. 633, 86 N.H. 501, 1934). The picture showed footprints in blood on a linoleum floor, and brought out distinctive marks in the soles of the shoes worn by the defendant that corresponded to the marks shown in the ultraviolet photograph.

In 1938, the Eastman Kodak Company introduced the Super-Six-20, which was a camera featuring fully automatic exposure control by means of a photoelectric cell coupled to the diaphragm of the lens. After 1945, Kodak again introduced cameras that were automatic and in a price range that everyone could afford. Today, such features are used in most cameras and are within a price range that is affordable to most people. You can get an automatic camera that meets almost all of a person's photographic needs, and most cell phones are equipped with sophisticated camera systems. There are even lens attachments, such as Sony's QX Cyber-Shot, that can be mounted to digital tablets and smart-phones to create a high-end camera system.

The first appellate court case passing on the admissibility of color photographs was Green v. County of Denver (142 P.2d 277, 111 Colo. 390, 1943). The court upheld the use of color photographs as evidence.

The Eastman Kodak Company introduced a color transparency using sheet film in 1935, called Kodachrome. It quickly became extremely popular, resulting in the widespread use of color photographs in police photography. Then, in 1941, a color process known as Kodacolor made it possible to make color slides, color prints, or black-and-white prints from a color negative.

In 1963, the Polaroid Company introduced Polacolor film, which made it possible to take finished pictures in black-and-white or color in less than 1 min. This was one of the most significant developments in the history of photography and led to the extensive use of color photographs as evidence. Many Polaroid camera devices were incorporated into traditionally police photographic uses, such as mug shots, fingerprint photography, microscope photography, and forensic photography. Digital photography has replaced Polaroid as the primary police camera system.

In 1965, another important invention was placed on the market. It was the introduction of a fully automatic electronic flash unit, which made it possible to take exposed strobe flash photographs at distances from 2 to 20 feet without changing the lens opening or shutter speed. Automation was thus achieved by means of the lighting equipment rather than the camera.

In 1967, we saw the beginning of the use of videotapes as legal evidence. Sony introduced the Betamax videotape cameras and recorders/players in the mid-1970s, making them affordable for the average household. At the same time, the Matsushita Company introduced the VHS series of cameras and recorders/players in direct competition of the Betamax system. Consumers chose the VHS over the Betamax. Today, many law enforcement agencies use videography for surveillance, recording crime scenes and interrogations, and training purposes.

In the 1980s, we saw the introduction of quality 35 mm "point-and-shoot" cameras, fully automatic 35-mm SLRs with automatic lens focusing, and a host of new and better films. During the late 1980s, we saw faster personal computers with high memory capabilities, allowing for the introduction of the CD Photo system and digital imaging.

The 1990s produced more advances in the field of photography than in previous decades. Primarily because of the progress of electronics and computer systems, new photographic media were developed. During the late 1990s, a new photographic medium emerged, digital imaging. When the digital video disc (DVD) was introduced in the late 1990s, it set the stage for the eventual replacement of the videocassette, the laser disc, the CD-ROM, and even the audio CD with one system for digital media storage. The DVD is now being replaced with portable chip devices in "flash drives" and digital smart-cards.

Today's twenty-first century cameras are fully automatic, to an extent. The police photographer can now concentrate more on the subject of the picture than on the intricacies of the camera. Professionals and amateurs now use cameras equipped with semiautomatic or fully automatic controls. Digital imaging allows photographers t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- DIGITAL ASSETS

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1 The Police Photographer

- CHAPTER 2 Cameras

- CHAPTER 3 Optics and Accessory Equipment

- CHAPTER 4 Light Theory and Digital Imaging

- CHAPTER 5 Photographic Exposure

- CHAPTER 6 Flash Photography

- CHAPTER 7 Crime Scene Photography

- CHAPTER 8 Motor Vehicle Incident Scene Photography

- CHAPTER 9 Evidence Photography

- CHAPTER 10 Ultraviolet and Infrared Imaging

- CHAPTER 11 Identification and Surveillance Photography

- CHAPTER 12 The Digital Darkroom

- BIBLOGRAPHY

- GLOSSARY OF TERMS

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Police Photography by Larry Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Criminal Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.