eBook - ePub

The Routledge Research Companion to Digital Medieval Literature

This is a test

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Research Companion to Digital Medieval Literature

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Working across literature, history, theory and practice, this volume offers insight into the specific digital tools and interfaces, as well as the modalities, theories and forms, central to some of the most exciting new research and critical, scholarly and artistic production in medieval and pre-modern studies. Addressing more general themes and topics, such as digitzation, media studies, digital humanities and "big data, " the new essays in this companion also focus on more than twenty-five keywords, such as "access, " "code, " "virtual, " "interactivity" and "network." A useful website hosts examples, links and materials relevant to the book.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Routledge Research Companion to Digital Medieval Literature by Jennifer Boyle,Helen Burgess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The digital and medieval (new) media

1

The remanence of medieval media

By the double logic of the remediating turn, the influence and effect of media does not flow singularly from present to past, any more than media historically develop in a monolithic line from past to present.1 What comes from before can only survive encoded in a physical substrate. Regardless of its original form and function, in the present this substrate assumes the function of media, as the past may only be understood forensically through information encoded within or by material survival. Such medieval media, in turn, are inevitably processed and re-presented through later forms of media. The effect is one of ongoing recursion: the environment of newer media recondition past media’s survival within them, while formal suppositions about both past and present media forms merge to produce immediate and novel iterations of the past. Renderings of past media in new ones (as expected) fulfil present cultural and media biases, but they also generate imaginative and persistent surrogates, often unrecognized as shadowy supplements for the past they reproduce. This reality of medieval media is intensified by the increasing archival and multimedial capacity of the digital, which flattens temporal thickness and enhances the speculative immediacy of the past within its own present forms. This essay explores three instances of medieval media, one originating in the middle of the eleventh century and resurfacing in the middle of the sixteenth, one from the middle of the twentieth century, and one in our present digital moment. In each, acts of formal, technological excision ostensibly diminish the medieval source. But these acts are also opportunities to recognize the persistent, complex and transmedial nature that defines medieval mediality today.

Instance I: a remanent Old English text

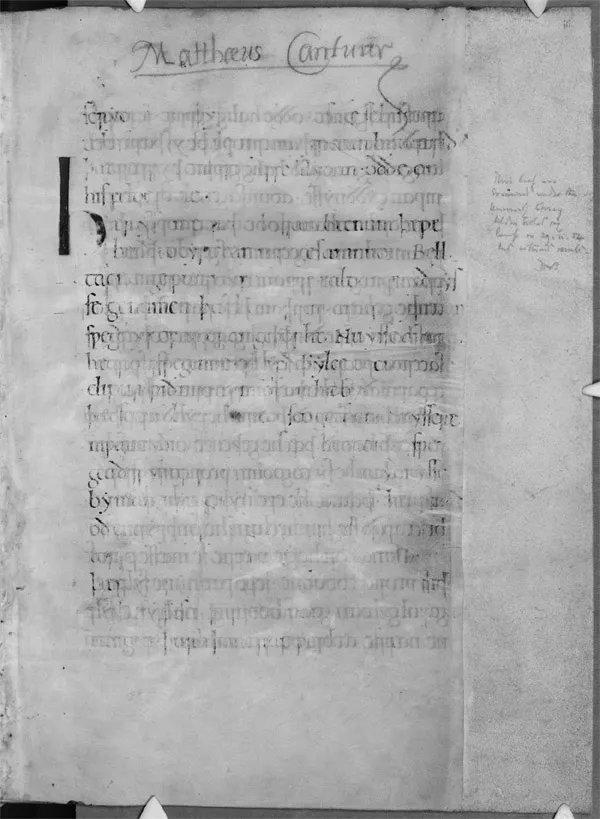

The first surviving page of Corpus Christi College Cambridge MS 44 (hereafter CCCC 44), a Latin pontifical, has barely survived at all (Figure 1.1). The manuscript was written in the mid-eleventh century, probably at Canterbury.2 Though the remainder of this book is in Latin, as is usual for a pontifical, the first three pages are written in Old English, in the same scribal hand as the rest of the book. The surviving vernacular text preserves a very small section of a very large theological treatise – a brief exposition of the allegorical significance of ringing church bells to call people to worship, redacted from a chapter in Amalarius of Metz’s ninth-century Liber Officialis (Book 3.1). The first extant page of this translation has been largely erased, almost certainly in the sixteenth-century by or under the direction of Matthew Parker, whose rubricated signature (Matthæus Cantuar[iensis]) adorns the top of this page.3 While the writing of the second and third pages of Old English text remains largely intact, there is visible evidence of each of the attempts to erase them as well; presumably the effort was abandoned, perhaps because of the physical labor it entailed.4 Matthew Parker is the antiquarian Archbishop of Canterbury best known (ironically here) as the figure almost singlehandedly responsible for finding and preserving hundreds of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts after the dissolution of the monasteries in England.

Figure 1.1 MS 44, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, p. iii (c. 1050, Canterbury)

Source: Reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, though as faithful facsimile of text already in the public domain, permissions are not technically required for publication.

In the case of this Amalarian text, Parker’s erasure only continues the shrinkage of source begun more than 700 years before. A Frankish ecclesiast during the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, Amalarius produced three editions of his massive Liber Officialis between 820 and 835. The final work is a formidably large text organized into four books and one hundred and fifty-eight chapters. Somewhere around 850, a much shorter redaction of the third edition was produced, known now as the Retractatio Prima.5 The Retractatio was the version that became known in Anglo-Saxon England, after coming over from Brittany and being copied in England by the early tenth century.6 This Latin redaction has survived in a number of Anglo-Saxon variants, including one from about the year 1,000 in Cotton MS Vespasian D. xv. This Retractatio Retractationis (to give it a suitable name) is a series of heavily edited excerpts from the Retractatio – so, a redacted redaction.7 This version introduced a number of corruptions into the Latin, in places muddling or altogether changing its meaning.8 The Old English version in CCCC 44 is a direct translation of this corrupted redaction of a redaction, a scrap of Amalarius’s mammoth work, surviving in a three-page excerpt with no clear context for inclusion, and no attribution of its original author.

Matthew Parker knew none of this particular text’s history when he encountered it and sought to wipe it from the page. But his desire to delete was most likely an intuitive one, formed out of a reflexive reaction to the fragmented, vestigial material record before him, and one unwittingly aligned with the text’s own history of transmission. The words on the page Parker saw were orphaned, cut off from any immediately graspable context, purpose, author or reason to interpret, far removed from any immediate sense of a “source.” From a traditional, teleological mode that regards textual source and transmission as a depreciating process, Amalarius’s original text had been vanishing for centuries, and Parker was, in effect, simply trying to finish the job.

In its present-day form, page iii of CCCC 44 has become remanent. Remanence, a concept borrowed from cyber-forensics, is what is left behind on the materials of media after information is removed. No erasure from a physical medium can ever be total, as content deleted always leaves behind some kind of residue.9 Remanence allows a part of what has disappeared in the past to be traced in the present, and therefore reimagined. A palimpsested medieval manuscript page is remanent in analogue; in 1995, Timothy Graham recovered all of CCCC 44’s erased text through technologically enhanced reading, using natural, ultra-violet and cold fiber-optic light.10 Remanent moments such as these concern more than the recovery of old information, and the subtraction of what existed before does more than produce a demotic version of a source. Any act of erasure also encodes new information on the surviving substrate, enriching its status as both archive and communication. Remanence can also apply more broadly and abstractly to critical inquiry, in terms of what scholarly heritage and hermeneutic conditioning has removed from the record of the material past, and how alternative approaches to the formal environments of material, text and technology may recoup what has been subtracted.

Instance II: photocopying the forensic imaginary

Technological advances in information management likewise tend to produce demotic biases towards the media forms they are designed to supplant. For the 1977 Super Bowl (where, somewhat aptly for the topic, the Raiders played the Vikings), Xerox produced a television commercial for its new 9200 duplicating system.11 The commercial’s conceit was so effective that it won every top award given by the advertising industry, was judged by the New York Times one of the top twenty-five commercials of the twentieth century, and became the advertising basis for flagship Xerox products for much of the next decade.12 The commercial features Brother Dominic, a medieval monk, who is tasked by his superior with making five hundred copies of a set of manuscript folia he has just completed. Faced with this impossible order of mass production, Dominic has an epiphany and takes a city bus to a modern skyscraper to ask a favor from the “Central Reproduction Department” of a corporate office. There he learns all about the features of the Xerox 9200, including its two pages per second reproduction and collation rate, and “computerized programmer that controls the entire system.” His five hundred copies quickly in hand, Dominic returns to the monastery, and the commercial ends with his superior first gazing on the stack of copies, and then heavenward, pronouncing, “It’s a miracle!” (Figure 1.2).13

Jack Eagle, the actor who played Brother Dominic, noted in a 1982 interview that the commercial “shows the Church in a modern atmosphere. It takes them out of the Middle Ages.”14 The ad campaign and its successors (including staffing exhibitions at industry trade shows with representatives dressed like monks,15 and the marketing campaign for Xerox’s first personal computer (Figure 1.3)) make their temporal, technological supersessionary agenda explicit by forensically imagining the medieval world as an outmoded one in both the past and the present. The spot opens with Brother Dominic as a fatigued scribe, massaging his temples, as a voiceover intones, “Ever since people started recording information, there’s been a need to duplicate it.” The narrative arc of the commercial removes the scribal manuscript source that opens the ad, replacing it in the information economy with a pristine stack of automated print, and it constructs Brother Dominic as a proxy for the modern viewer, and pre-Xerox office labor as the medieval Church. Without the Xerox 9200, your information management is unambiguously “medieval.” Computerized text and image reproduction, new on the scene in 1977, presents as a miraculous future made immediate, one which will save you as it did Brother Dominic, as if by a literal deus ex machina.

Formal, forensic materialisms

Today, the easiest, practically the only, way for most people to view either the erased page of CCCC MS 44 or the Xerox Super Bowl commercial is through digital media.16 Regardless of the material truth of a media form, its reality derives from beliefs about its materiality, which dominates how we then assess both its function and content. In his study of digital media, Matthew Kirschenbaum develops the notion of “formal materiality” to expose the misapprehension that digitality is by nature ephemeral and non-material – 1’s and 0’s floating in the ether. Instead, like all media, the digital is always a physical phenomenon, but has been modelled as incorporeal: “a digital environment is an abstract projection supported and sustained by its capacity to propagate the illusion of immaterial behavior.”17 Kirschenbaum distinguishes formal materialism from forensic materialism, the physical reality of media, and the way information encoding marks and individuates the material substrate of any instance of media.18 To expand Kirschenbaum’s notion historically, various abstracted, material beliefs inform the reception of all media, and the interaction of forensic and formal materialisms attend any study of the past. Modern subjects who engage or reproduce surviving medieval media forms both excavate the material record and reinvent it through the formal materialities of the technologies they employ.

Remanent media such as the first page of CCCC 44 and forensically imaginative ones such as the 1977 Xerox Super Bowl commercial invoke medieval mediality through related crises in information management that are both conceptual and textual in nature. The crises derive from discovering the compromised status of the medieval source – Brother Dominic’s scribal production formally cannot meet the needs of subsequent mass reproduction, while Matthew Parker’s attempted erasure of the Old English Amalarian fragment forensically documents an almost literal vanishing point of the writing’s ultimate textual source. These moments engineer a medieval past that is manifestly linear and teleological. Brother Dominic’s physical labor as a scribe – the human mouvance that the monk imparts to the written product – is contrasted to the rapid and automated technological homogeneity of the Xerox 9200 designed to succeed it.19 In homology with Brother Dominic, Parker’s erasure of CCCC 44 enforces the hierarchic ideology of source and copy that largely governs the nature and value of surviving medieval text, with attendant, platonic consideration of the corruption that accompanies transmission and copying. These two examples together encapsulate teleological impulses for understanding surviving medieval modes of textual transmission and reproduction. In a classic formal materiality of the medieval manuscript, earlier and more complete texts are privileged over copies that follow.20 The canonic formulation of media history (as realized in the Xerox commercial) reverses but maintains the integrity of this relation, as the latest becomes best, and the modern copy becomes the desir...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Introduction: resistance in the materials

- Part I The digital and medieval (new) media

- Part II Remediating medieval literature

- Part III Medieval materialities, digital modalities

- Part IV “Screening” the medieval: visualization and modes of interoperability

- Part V Current conversations

- Index