1.1 The Age of Mobility

A little over 50 years ago a report on Traffic in Towns was published by the UK Government (Ministry of Transport 1963). Written by Colin Buchanan, it became an influential guide to accommodating the motor car in towns and cities. The report identified the trade-offs required between allowing accessibility by car, the effects on the built environment and the costs involved. It was difficult to accommodate traffic in historic town centres, for example, without costly measures to mitigate their impact; hence cheaper traffic management measures and pedestrianisation schemes were preferred. In other centres where the environment was of lower quality, redevelopment was possible to accommodate cars in multi-storey car parks as part of shopping malls. Thus, the scene was set for the segregation of cars in towns where the environmental impact and cost were justifiable.

Fast forward to the present day and the legacy of Traffic in Towns is evident throughout the country. Where traffic constraint has not been applied, car-oriented development and traffic congestion is pervasive. Despite our attempts to re-model the city and accommodate cars, the results are less than impressive. The car has accelerated suburban sprawl, contributed to the demise of some town centres – contrary to what Buchanan intended – increased congestion despite massive investment in roads and traffic management schemes, caused thousands of deaths and injuries and polluted the environment to such an extent that transport is a major contributor to climate change through carbon emissions. It is also recognised as a factor in promoting less healthy lifestyles and obesity. And these problems are chronic, with no sign that they will be alleviated any time soon.

These problems were predicted by some commentators in the years following the Buchanan Report, highlighting that changes in car ownership and mobility would have far-reaching effects on society at large and the political economy of transport, specifically the demand for more road infrastructure and the redevelopment of cities to accommodate the car (Townroe 1974). The sceptics were prescient in forecasting the wider implications of the car on politics and social culture, and through the 1970s an increasing number of academics and analysts began to question whether car ownership and use was good for society, arguing that more convivial modes of public transport were more appropriate to urban lifestyles (for examples see Plowden 1972, Towns Against Traffic, and Bendixson 1974, Instead of Cars).

Their concerns, however, rarely resonated with the general public, politicians, opinion formers and the majority of the transport profession, who at that time viewed rising levels of prosperity and mobility in the post-war years as a positive trend and part of the modernisation of society – broadening social mobility and spatial horizons through greater travel freedom and boosting economic performance. In short, auto-mobility was regarded as a liberating force that since the 1950s had benefitted those on lower incomes and not just the middle class. But as mass car ownership spread, so did the problems associated with traffic growth – pollution, congestion, accidents and community severance. In response governments and the auto industry have put into place a range of mitigation measures that have improved the safety and fuel efficiency of automobiles, together with better traffic management. However, they have been less effective in tackling congestion, pollution and wider environmental impacts, the social exclusion of those without access to a car, and the rising cost of transport (public and private) to the individual and the public purse. The outlook does not look good, especially given the rise in population and traffic forecasted for the decades ahead. What was once seen as a liberating mode of transport is now regarded by many policy makers and opinion formers as a nuisance that needs to be regulated and controlled more effectively if we are to make our cities more liveable.

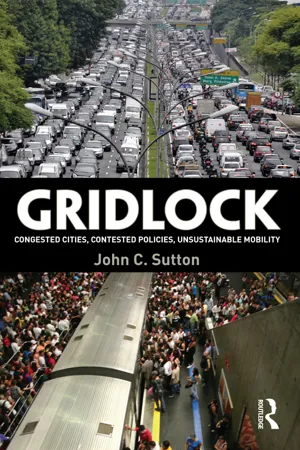

The dilemma facing politicians and policy makers is how to accomplish this. There are solutions on offer – explored in later chapters – but they all present challenges and require hard choices. These are problematic to politicians and arouse suspicions among members of the public, business and other constituencies who fear that they will lose out in whatever bargain is struck. In short, there is no consensus among politicians, professionals or the public: indeed, transport policy and planning has become more contentious and is likely to become more political and contested in future. More than in most other countries, transport policy and planning in the UK has become a battleground among competing ideologies and policy discourses. Transport and mobility has become an arena in which competing political philosophies are put into practice, often behind a veneer of economic theory and environmentalism. The result is gridlock on the streets as well as in policy.

On one side is the sustainable transport narrative, which aims to reduce mobility by improving accessibility by non-auto modes and the remodelling of cities around smarter travel and smarter urban development.1 We may characterise this as the ‘convivial transport’ movement, which emphasises public transport, cycling and walking solutions. Juxtaposing this is the auto-mobility culture, which idealises the conspicuous consumption of mobile paraphernalia – cars, air travel and mobile telephony. Sustainable transport is the counterfactual to the mobile lives that most people aspire to in a culture driven by competition and market forces. Convivial philosophies of smarter travel and sustainable transport are the antithesis of a ‘competitive transport’ system. These two discourses currently dominate transport policy and give rise to contradictory solutions. Convivial transport advocates smarter choices, regulation and public policy interventions to deliver a more sustainable transport system. Competitive transport supports liberalisation and privatisation of transport services with market economics driving transport policy, such as road pricing solutions to choke off excess demand. The contradictions evident in these two approaches reflect different views or ideologies on the role of transport in society. Is it to support economic growth, travel choice and personal mobility? Or is it to promote equal accessibility, environmental justice and more collective transport solutions? The current narrative among politicians, and broadly accepted by the transport profession, is that we can do both, or at least mix-and-match policies sufficiently enough to deliver a (convivial) sustainable transport solution within a (competitive) transport system. This is embedded in current transport practice and the policy discourse of sustainable transport.

This discourse and the accompanying narrative constitutes ‘Plan A’ for tackling climate change, traffic congestion, pollution, road safety and other transport issues. This plan also includes measures to boost the economy by selective investments in road, public transport, airports and port schemes. As will be discussed later, the Government and some transport organisations see no contradiction between policies that boost mobility with policies that aim to reduce travel demand. If these policies fail to meet CO2 and congestion-reduction targets, there is a ‘Plan B’, long advocated by some elements of the transport sector: namely, congestion pricing for road users. This policy, successfully implemented in some cities, is regarded by its supporters as the only feasible solution to matching demand and supply, and providing the revenue stream for more investment in infrastructure. It may be a sound economic solution, at least in theory, but runs into a number of political and cultural barriers, which so far have restricted its deployment in the UK to central London. Perhaps its biggest problem is that it is a regressive tax on people's mobility and would have major impacts on business as well as individuals. Outside the ivory towers of academia, policy think tanks and a few transport lobbies, there is little enthusiasm among politicians or the public.

The policy conflation of convivial and competitive transport measures (in Plan A, Plan B or a combination thereof) is a compromise that falls short of what is required to meet sustainable transport goals or deliver sufficient supply-side improvements to mitigate congestion and gridlock. Integrating the two policy perspectives requires balancing social consumption and social investment. Convivial transport solutions do not adequately address social consumption needs of the population or the political-economic demands of capitalism. A competitive transport system cannot keep up with the demands for social investment, leading to increasing congestion and inefficiency. Eventually the transport system will collapse under the weight of its internal contradiction; that is, investment cannot keep up with congestion (Nair 2011).2

The premise of this book is that both Plan A and Plan B are not deliverable for economic and political reasons, and consequently are not robust enough to resolve the transport and mobility challenges the country faces. And these issues are not just confined to the UK but are international in scope. Wherever rising mobility expectations combine with more affluence and population increase, the consequences are insufferable levels of congestion that will become critical in the next decade. This book outlines a ‘Plan C’, which takes elements of the other two plans and adds a key requirement to limit mobility demand to the transport supply available and thus control the level of congestion. It accomplishes this through the application of information and communication technologies allied to a strategy of mobility management. Unlike the other two plans, this policy is progressive, fairer and more equitable. The rationale for this solution is explained in the chapters that follow.

According to the current sustainable transport narrative, the most pressing problem facing transport is the environmental impact of auto-mobility and specifically the problem of carbon emissions, which are contributing towards anthropogenic climate change. In consequence, agreements have been reached to reduce CO2 and other emissions from cars by means of improving fuel efficiency, capturing tailpipe emissions, switching to electric propulsion systems, car-sharing schemes and promoting the use of alternative modes. Notwithstanding the reality of climate change, the pending crisis in transport is not environmental pollution but congestion. Congestion will create the conditions for unsustainability mobility, which will impact on communities across the globe before the world's climate reaches the forecast rise of two degrees Celsius by 2050.

My prediction is that congestion is already a factor in economic and social organisation and will become ever more limiting over the next two decades. So much so, that by the 2030s the politics and policies of transport and mobility will alter radically, ushering in a new sustainable mobility settlement. This will contain some of the actions and initiatives advocated by the sustainable transport lobby, with two fundamental differences: firstly mobility freedoms will be sacrificed in order to preserve economic and social stability; and secondly environmental impacts will be mitigated by advances in technology. How this will be accomplished is discussed in the following chapters, which examine the future of transport and mobility through three propositions – see Box 1.1.

Box 1.1 Towards Sustainable Mobility – Three Propositions

The first proposition is that resolving transport and mobility problems related to increasing congestion, travel cost, safety and climate change (based on carbon emissions) will be significant drivers of transport policy and the conflicts between them will produce more radical solutions than has hitherto been contemplated. Smarter travel measures may mitigate some mobility problems but only succeed in delaying the inevitable mobility crisis.

The second proposition is that technology will play an increasing role in managing...