1.1 Introduction

When we say we ‘can’t see the wood for the trees’, we are expressing a need to establish a general picture of something that is more than the sum of its parts. Categorising and classifying things we encounter in everyday life are therefore important steps in the process of imposing some kind of order on the infinite varieties of human experience: they are part of a general strategy of ‘making sense of the world’ by artificially reducing variation to manageable proportions. For example, it is both conceptually and communicatively more economical if we can classify tulips, roses and daffodils as members of the general category flower or Volkswagens, Fords and Nissans as belonging to the category car (or automobile).

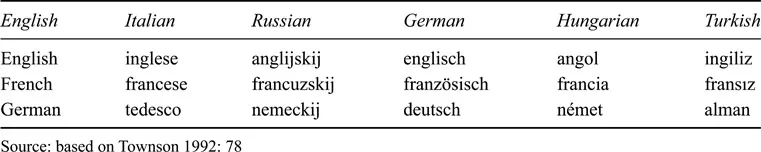

Naming languages is a similar process, but allocating individual varieties to a particular language may be more arbitrary and more complicated than is the case with types of flower or car, and there may be other reasons than convenience or communicative efficiency for doing so. Furthermore, the names themselves are more than mere labels and may reveal a great deal about the relationship between the linguistic forms and their speakers. Consider, for example, the names for English, French and German in Table 1.1. A glance from left to right across the table should reveal at least two interesting points in this respect: firstly, the fact that many different languages use (versions of) the ‘same’ name to designate English and French; second, the fact that there is, by contrast, no general agreement on how to designate German. European language names are most commonly based either on the names of tribes or peoples (here, for example, Angles and Franks) or on the names of geographical locations; some of the labels used for German follow these two patterns, but others derive not from people or places but from language itself.

- Can you think of any controversies concerning the naming of languages? (You could think, for instance, of the situation in the former Yugoslavia or the relationship between Czech and Slovak; the linguistic dispute in the Republic of Moldova; the two names given to Spanish (español vs. castellano); or the different names given to Chinese.)

Table 1.1 Nationality/language adjectives in a range of languages

1.2 Historical overview of Germanic languages

From a contemporary synchronic perspective, the label deutsch has linguistic, ethnic and geographical applications: we may talk of die deutsche Sprache, die Deutschen, Deutsch-land. However, if we consider it diachronically, we find that its use to designate a language predates its use in reference to people and places. In other words, the constitution of the ethnic or national group derives from the idea of a ‘common’ language, and this is what makes the German case particularly significant in the European context (see Chapter 2): any attempt to define the elusive concept of ‘Germanness’ has to start with the language. However, this creates more problems than it resolves:

Wenn Helmut Kohl im Laufe der Jahre 1989–1991 wohl hundertmal von der Einheit des deutschen Volkes gesprochen hat, dann ist klar, daß dies nur Bürger der alten/neuen Bundesrepublik Deutschland betrifft, also die Deutschen. Und es ist ebenso klar, daß Schweizer, Liechtensteiner, Österreicher usw. zwar Deutsch sprechen, aber keine Deutschen sind. Die semantische Aufgabenverteilung scheint gelöst zu sein.

Trotzdem ist die Sache so einfach nicht. […] Was weithin übersehen wird, ist die Tatsache, daß es sich hier in hohem Maße schlichtweg um ein terminologisches Problem handelt, das unlösbar ist. Hieße die Bundesrepublik Deutschland etwa Preußen, dann wären Preußen, Österreich, die Schweiz usw. einfach deutsche oder teilweise deutsche Länder. Dem ist nicht so. Die Realität beschert den deutschsprachigen Ländern außerhalb Deutschlands auch auf weitere Sicht den alten Konflikt zwischen Staatsnation und Sprachnation und die Frage nach dem jeweiligen Deutschsein dieser Staaten. Gerade während der letzten Jahre ist diese Frage angesichts der erreichten Einheit Deutschlands wieder aktuell geworden. Sie wird jedoch – bei verschiedenen Ausgangspunkten – in der Schweiz und in Österreich schon seit einigen Jahren verstärkt diskutiert. In dieser Diskussion führt kein Weg am Faktum der Staatssprache Deutsch vorbei, die dort eben nicht etwa nur Bildungs-oder Verwaltungssprache ist, sondern Volks-und Muttersprache seit Anbeginn.

(Scheuringer 1992: 218–219)

So just when we thought we had identified a neat relationship between ‘the German language’ and ‘the German people’, we find that things are actually more complex. Scheuringer’s argument, for example, confronts us with a number of questions:

- If ‘the German language’ is in some sense the cornerstone of ‘the German nation’, what does this mean for ‘the Austrians’ or the 75 per cent of Swiss citizens whose first language is German?

- What does it mean for the millions of citizens of other states all over the world who consider German to be their ‘mother tongue’? Conversely, what implications does it have for those living in Germany (or Austria) for whom German is a second or foreign language?

Even if we restrict our consideration of the word deutsch to the relatively recent past (for example, post-1945), we can see that its multiple uses and connotations provide a key to many of the currents of social and political history in the centre of Europe. The official names of the two German states that existed between 1949 and 1990 were Die Deutsche Demokratische Republik and Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. While the former was often abbreviated to DDR (in German), both in the GDR itself and in the FRG, even in official contexts, the German abbreviation BRD was never officially sanctioned in West Germany and from the late 1970s was actually prohibited. A university professor, who had used the short form in an official letter, received this stern rebuke from the Bund Freiheit der Wissenschaft (a small group of conservative academics):

Wie Ihnen sicherlich bekannt ist, ist der Ausdruck „BRD“ ein semantisches Kampfmittel der DDR gegen die freiheitliche Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Dieses Kampfmittel wird mit aller Konsequenz auch von den extremistischen Kräften in der Bundesrepublik angewandt, die mit unserer freiheitlichen Grundordnung nichts anzufangen wissen und sie bekämpfen.

(Glück and Sauer 1990: 20; originally cited in Die Glottomane 4/1976: 6)

- Why do you think a seemingly innocent abbreviation would be considered threatening?

During the existence of the two Germanies, West Germans had increasingly come to use deutsch and Deutschland with reference to themselves and their state. Similarly, it was commonplace for many West German organisations and institutions to include the word deutsch in their title (Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, Deutsche Welle). However, while some organ-isations in the GDR did so too (Deutsche Reichsbahn), many either concealed it by the consistent use of an abbreviated form of the title (FDJ for Freie Deutsche Jugend, ADN for Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst) or changed their name (Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften became Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR). From 1990, deutsch and Deutschland rapidly re-established themselves as demonstrative emblems of national unity. For example, a trade magazine for butchers proudly declared: ‘Der deutsche Wurstfreund kann seinen Tisch mit über 1500 leckeren Sorten decken. Dafür sorgen Deutschlands gewissenhafte Fleischer. […] Genießen Sie also die Abwechslung und den Geschmack, die der große deutsche Wurstschatz bietet’ (Glück 1992: 153; originally in Lukullus Fleischer-Kundenpost 31/1990: 2).

- In the light of what we have said previously, what do you think was the political significance of the gradual disappearance of the word deutsch from public discourse in the GDR? Consider, for example, the wording of the following extracts from different versions of the GDR constitution:

Preamble

Von dem Willen erfüllt, die Freiheit und Rechte des Menschen zu verbürgen, […] hat sich das deutsche Volk diese Verfassung gegeben.

(1949 version)

Erfüllt von dem Willen, seine Geschicke frei zu bestimmen, […] hat sich das Volk der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik diese sozialistische Verfassung gegeben.

(1974 version)

Article 1, clause 1

Deutschland ist eine unteilbare demokratische Republik.

(1949 version)

Die Deutsche Demokratische Republik ist ein sozialistischer Staat deutscher Nation.

(1968 version)

Die Deutsche Demokratische Republik ist ein sozialistischer Staat der Arbeiter und Bauern.

(1974 version)

1.3 The problem of definitions: what is German, who are German-speakers?

Much of the discussion in the previous section took for granted the existence of a discrete set of linguistic forms that can readily be subsumed under the label the German language. As with many other abstract concepts (goodness, happiness, beauty), the prevailing view of this notion is based on a paradox: we readily accept that there is such a thing, that it is somehow self-evident, and yet cannot find any convincing way of defining it. In other words, we are generally confident of being able to identify whether a stretch of speech is German or not, but we have no watertight and universally agreed criter...