Crazy Drake’s Folly

TODAY, the hills of northwestern Pennsylvania are scarred by strip mining and mountain topping. But 150 years ago they were wilderness. Black bears and wolves roamed the woods, pausing to drink from mountain creeks that ran cold and clear. It was along one of these creeks that Colonel Edwin Drake and his band of explorers clambered in search of oil. The year was 1858, and a youthful United States of America was growing fast, taking the reins of the industrial revolution from Great Britain with the help of a seemingly endless supply of natural resources. Coal from the hills of northwestern Pennsylvania powered the locomotives and ships carrying the U.S. to global preeminence, but coal wasn’t easy to get at. In those days before strip mining and mountain topping, deep mining was the only way, and that was dangerous and expensive.

Drake and his men weren’t looking for coal, though. They had their eye on the next big thing, a fuel with 66 percent more energy per pound than coal. They were after oil, so plentiful in northwestern Pennsylvania that in some places it covered the ground with a swampy slick. Some creeks sparkled with the rainbow-colored sheen of perpetual oil slicks as oil bubbling up from below ground was carried downstream. It’s no wonder that Drake chose to search along one of these, the one called Oil Creek.

As they trudged along its wooded banks, his men carried a kind of rigging never before used in the search for oil. Before Drake, oil had only been harvested from surface slicks, called seeps, like the ones that dotted northwestern Pennsylvania. But Drake was after bigger game than that. He and his men were hauling timbers, pipes, and augers to make the kind of rigging that until then had only been used by salt miners to extract subterranean salt brine. No one had ever thought to go to the trouble of drilling for oil. But with the new nation’s thirst for fuel skyrocketing, the Seneca Oil Company had hired Drake to try his brash new scheme.

Things went poorly at first, earning the rig the nickname “Drake’s Folly” and the Colonel the nickname “Crazy Drake.” But Drake would have the last laugh. In 1859, he and his crew struck oil at a depth of 69 feet. A new “oil rush” was underway, and soon oil rigs were sprouting up all over northwestern Pennsylvania. Suddenly, America had a bold new source to power its expansion westward, and the supply appeared to be as endless as the demand. Only one obstacle stood in the way. The crude oil discovered by Drake and others was of little use in its natural state, and oil refineries barely existed in the 1860s.

Figure 1.1: Drake’s Folly

The first oil well in the U.S. was 69 feet deep. Today’s wells can reach deeper than seven miles in search of oil. Image courtesy of Drake Well Museum, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

One enterprising young man, however, saw oil’s potential to power the nation’s westward expansion. This son of a snake oil salesman saw coal prices rise by 50 percent over the course of the Civil War, and he saw oil as an attractive alternative. He also saw the missing link between the oil wells of Pennsylvania and the rising demand for power to the west: refineries. In 1862, at just 21 years of age, he began amassing the resources to buy a small Cleveland refinery located along the new Atlantic & Great Western Railroad that would link the Pennsylvania oil fields to the American West. By 1865 the refinery was his, and within six years he and his partners owned every refinery in Cleveland. Eight years later, his company was refining nine out of every ten barrels of oil produced in the United States. By 1890, the Standard Oil Company would be one of the world’s wealthiest companies, and the young man, John D. Rockefeller, would be the nation’s first billionaire—a wealth built on oil.

Fueling the American Dream

HOW did oil grow from Drake’s Folly to become the world’s most profitable commodity in just 30 years? The answer can be found in a bicycle shop in Germany. In 1885, just as John D. Rockefeller was becoming the world’s richest man, Karl Benz was putting the finishing touches on his new invention, an “automobile fueled by gas.” Sales were slow at first, since no one but Benz had ever considered gasoline as a fuel. In fact, his first customers had to buy gasoline from pharmacies that sold it as a cleaning product. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, Benz was producing over 500 cars per year. Within four years, sales would top 3,500.

But gas was by no means the only power source for this new mode of transportation. In 1906, American Fred Marriott set a land speed record of 127 mph in a Stanley Steam Racer, and Stanleys were some of the most popular vehicles in the fledgling U.S. auto industry. Only the Columbia Automobile Company, with its line of electric cars, outsold Stanley. But the Steamer didn’t require an electrical outlet (scarce in 1906) or a stop at the gas station. Instead, drivers simply pulled up to a horse watering trough and siphoned out what they needed. The Steamer, however, became a victim of its own success. More cars on the street meant fewer horses, and that meant fewer watering troughs. Soon finding one to refuel from became harder than finding an electric car refueling station is today.

But it wasn’t just the nation’s vanishing horse troughs that brought about the decline in steam- and electric-powered vehicles. While the Stanley and Columbia factories in Connecticut and Massachusetts made the Northeast the center of the U.S. auto industry, a former sawmill operator from Michigan was hard at work on another power source. In 1908, he and his partners ponied up $28,000 to start a new company making gas-powered cars they hoped would rival Stanley and Columbia. By 1916, nearly half a million cars per year would be rolling off the assembly lines of their Ford Motor Company. Their Model T cars sold for under $400, while the Stanley Steamer cost almost ten times as much, putting to rest any doubts about which fuel would power the world’s cars.

And while resistance would prove futile in the long run, other, often more efficient fuels continued to shape the American transportation landscape for years to come. Even Henry Ford designed his early cars to run on ethanol, calling it “the fuel of the future.” Electricity was another alternative, not for automobiles but for mass transit. As late as 1920, public mass transit was still the nation’s first choice for travel, and if you looked up from the city streets filling with cars, you would see the overhead lines of electric trolleys. To the oil and auto companies, however, those trolley cars were full of lost customers. Starting in 1936, two major bus lines working with investments from General Motors, Standard Oil, Philips Petroleum, and others, began buying up trolley systems across America. They tore down the overhead electric lines, tore up the tracks, and junked the cars. Eventually, GM and other companies would be convicted of conspiring to monopolize the sale of the buses that replaced the trolleys, but the damage was done—petroleum-powered buses and cars had won out over mass transit, electric and steam power.1

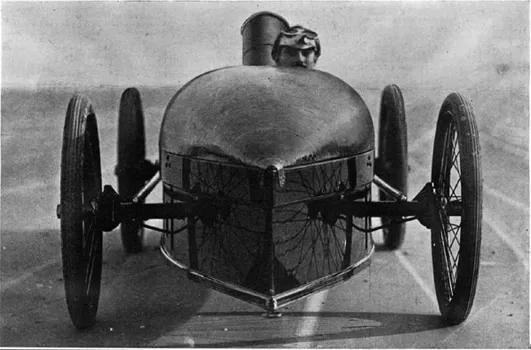

Figure 1.2: Stanley Steam Racer

In 1906, Fred Marriott set a land speed record of 127 mph in a Stanley Steam Racer at a time when steam-, electric-, and gasoline-powered cars vied for dominance of the world’s roads. Image courtesy of Scientific American.

Figure 1.3: Trolley Car and “Trackless Trolley”

World War II-era Baltimore commuters hustle to catch an electrically powered trolley (left) and a gas-powered “trackless trolley” (better known today as a bus). Image courtesy of Library of Congress; photo by Marjory Collins.

By 1960, Americans were driving 13 miles for every 1 they traveled by mass transit. One hundred years after Drake first struck black gold in the hills of northwestern Pennsylvania, over 70 million gas-powered vehicles would be rolling across the United States. Outnumbering single-family homes by more than ten to one, the car had supplanted the home as the new American Dream. For the auto and oil industries, it was a dream come true. General Motors was the nation’s largest company, Ford Motor Company was second, and Esso, now called Exxon Mobil and a direct descendant of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1911 antitrust breakup of Standard Oil, was third. The four-wheeled American Dream ran on gas, and together these mega-corporations virtually ran the country. But a single event in the early 1970s would lead us to wonder what happens when the pipeline that fuels the American Dream starts to run dry?2

Peak Oil

“A nation that runs on oil can’t afford to run short,” was the 1972 mantra of the American Petroleum Institute. The API had good reason to be concerned: two years earlier, in 1970, U.S. oil production, which had led the world since the days of Drake’s Folly, had begun to decline. To make matters worse, America’s thirst for oil was on the rise, doubling between 1950 and 1970. With consumption going up and domestic supplies going down, oil imports skyrocketed. Relying on foreign oil to fuel the American Dream, however, proved to be risky business.

The last place I wanted to be as a teenager in the summer of 1973 was stuck in the back of my parents’ station wagon, waiting in line to buy gas. It could take hours, and with purchases sometimes limited to ten gallons, it wasn’t long before we were back in line. By the end of the year, the shortages and high prices resulting from the boycott by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries were so severe that President Nixon declared a nationwide maximum speed limit of 50 mph. “Fifty is Thrifty” public service announcements soon flowed from the radios of cars stuck in the gas lines. Within a year, one in five gas stations was without gas, and the price of what was left had nearly doubled.

Figure 2.1: Oil Embargo Gas Lines...