![]()

1

____________________________________

____________________________________

PHILOSOPHICAL DEBATES IN ECONOMICS

A RIDDLE

A man and his son are driving to a championship football game. It is late December and the roads are covered with snow. They hit a patch of ice and crash into a telephone pole. The father is killed instantly. An ambulance rushes the son to a nearby hospital and operating room. The doctor walks in and says, “I can’t operate, that’s my son.” How could this be true?

Whatever your answer is to the riddle, assume that it is incorrect and come up with a second answer. We will return to this riddle shortly.

PARADIGMS IN ECONOMIC THEORY (OR WHY ECONOMISTS DISAGREE)

Definitions

A paradigm is a conceptual framework, a context for organizing thought. It is like a pair of theoretical spectacles used to observe and think about the world. There are competing paradigms for understanding the economy, competing frameworks for organizing economic theory. This chapter explores why competing paradigms (such as neoclassical economics, Marxist economics, and ecological economics) exist.

Thinking is hard. Thinking about thinking (epistemology) is even harder, but that is where we must begin if we are to fully understand economic debates. Epistemology refers to the study of the nature of knowledge, including how we determine what is true and even what we mean by “truth.” We shall begin by comparing two simple models of knowing: the “blank slate” theory of knowledge and the “paradigmatic” or gestalt1 theory of knowledge. Page constraints require that we skip over many subtle and fascinating issues, but if our brief inquiry whets your appetite, you might think about enrolling in a philosophy course that reads thinkers such as Descartes, Locke, Hume, Popper, and Kuhn.

Blank Slate Theory of Knowledge

Most people in our society, including most economists, accept a blank slate theory of knowledge, often without explicit recognition. For many people, blank slate claims seem commonsensical and self-evident. The blank slate theory of knowledge is often associated with empiricist philosophers. It imagines that the mind confronts the world directly. Individuals have experiences from which they generate ideas. It is as if ideas were imminent or pregnant in experience. You stick your hand in a fire and generate the idea “hot.” You look at a rose and generate the idea “beautiful.” Your mind reflects the world as if it were a mirror. The world writes on you as if you were a blank slate.

The world’s scribblings and reflections, however, are not always easy to interpret. After sticking your hand in a fire, you might, for example, mistakenly think that orangeness causes pain. Blank slate theories of knowledge thus require that all imminent ideas be treated as hypotheses and elevated to the status of provisional knowledge only after having survived experimental tests. The idea that orangeness causes pain, for example, would presumably be jettisoned after eating your first orange.

There is often an implied universality to blank slate knowledge claims. According to this reasoning everyone can in principle do the same experiments. Therefore all thinkers should eventually arrive at the same ideas. Variants of blank slate epistemology lie behind many popular expositions of the “scientific method.” Science is said to “command” our belief because it generates falsifiable (testable) propositions from experience and logical deductions. All scientists should, according to this view, eventually reach the same conclusions.

Conventional economic theory tends to adopt blank slate epistemology. It thinks of itself as a science, whose conclusions command belief. We shall see shortly why some economists disagree.

Paradigmatic Theory of Knowledge

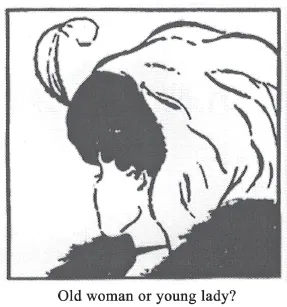

In contrast to the blank slate view of the mind, the paradigmatic view of knowledge argues that the mind never perceives the world directly or experiences sensations innocently, that is, untranslated, or unmediated by a person’s prior conceptual framework. According to paradigmatic theories of knowledge everyone is always wearing theoretical spectacles and thinking within some paradigm. What one sees is a product of what “is out there” and the lens used to study it. The accompanying picture provides a simple (and perhaps dangerously oversimplified) introduction to this idea. Look at it and write down what you see. Assume it came from a book about a young woman drinking wine.

I suspect that most of you saw an attractive young lady. Some of you saw an old lady. Why? If you look closely at the picture you should be able to see both versions of the person. The picture represents a classic example of figure-ground reversal, a topic studied in perceptual research. Although looking at the same picture, we perceive different scenes. By organizing the lines in different ways in our minds, we can “see” different things. In much more subtle ways, paradigmatic theories of knowledge claim that economists and other social theorists in competing paradigms “see” different things and understand the workings of the social world differently.

From a paradigmatic perspective, observation and thinking are active rather than passive processes. Instead of simply reflecting what is “out there,” the observer partially constructs what she sees. As a first approximation, it is helpful to think about paradigms influencing thought in four main ways, by their impact on: (1) the data attended to, (2) the abstractions used to organize data, (3) the language used to convey ideas, and (4) the way in which new theories are tested.

Data Attended To

As the philosopher William James notes, without editing sensations (that is, without focusing on some sensory inputs and ignoring others), the world would be a “bloomin’ buzzin’ confusion.” People’s conceptual frameworks help provide that editing, by telling people, “look here, and not there.” One’s theory of the mind, for instance, helps determine what psychologists and other counselors “hear” when they interview people.

Figure 1.1 Old Woman or Young Lady?

Adapted with permission from an Exploratorium postcard [http://www.exploratorium.edu/exhibits/postcard_illusions/] originally rendered by W.E. Hill. The illusion, sometimes referred to as the Young Girl–Old Woman illusion, is based on a 1915 cartoon in an American humor magazine, which in turn was based on an 1888 German postcard. See mathworld.wolfram.com and Al Seckel’s web site (http://neuro.caltech.edu/∼seckel) for additional information about this and other optical illusions. Thanks to all of these people and web sites for helping me utilize this image.

For example, consider the idea of a “Freudian slip.” According to Freudian psychology, the mind is multidimensional, including conscious and unconscious levels. Occasionally, instinctual energy from the unconscious bubbles into overt behavior, circumventing subconscious and conscious censors in devious ways. What a non-Freudian might treat as an inconsequential typographical error or slip of the tongue becomes for a Freudian a key piece of data, a window into the unconscious. When Freudian counselors “listen” to their patients, they often listen more for the silences (censored utterances) and irregularities (Freudian slips) than for explicit remarks. Non-Freudians listen and hear differently.

Similarly, some contemporary physicists build special instruments to explore the nature of matter. The instruments exist because of the presence of a theory that implies the existence of special particles (solar neutrinos) that can be measured by the instruments. Without the theory we would not have the instruments or data about the particles. We would not “see” them. In fact, we never do “see” them; we record some effects, which, given our theory, we interpret as their “reflections.”

As we shall discover shortly, different economic paradigms allow one to “see” different things. The paradigms orient us to different data and to different questions about the data. Conventional gross domestic product (GDP) statistics, for example, attempt to measure national economic output. They leave out, however, the value of things produced in the home for family use (because they are not priced in markets) and the value of social maintenance (that is, the cultivation of interpersonal ties that transform a group of people into a community). Feminist economists note that such oversights are not random; they often exclude the experiences and contributions of women in the economy.

Ecological economists have criticized GDP statistics for their incomplete treatment of “natural capital” (such as exhaustible resources or the earth’s capacity to absorb wastes). We will explore exactly what this means in the text. The point here is that even the numbers that economists use to “describe” the level of a country’s economic activity reflect paradigmatic visions. There is no neutral, objective, “theory-less” scale with which to measure economic activity.

Abstractions Used to Organize Data

Even when two observers “see” similar objects, people from different paradigms may organize their observations differently. People’s conceptual frameworks provide the categories (the concepts or abstractions) for linking and integrating observations. Marxist and feminist economists, for example, organize economic observations about inequality with respect to the customs and institutions of a social system. They knit together their analysis with categories that link individual actions to culturally given social roles. Neoclassical economists talk about individuals rather than social systems and have few categories or concepts linking individual behaviors to social structures. (Precisely what this distinction means will occupy us in chapter 2).

Language Used

Almost all paradigms develop specialized languages by using familiar words in special ways and occasionally creating new terms. Just as a paradigm’s abstract concepts are linked together, its language is interactively constructed. Groups of words are often used reciprocally to define each other, much like cross-referencing in a dictionary.

The language of a conceptual framework inevitably sh...