![]()

Forms and models

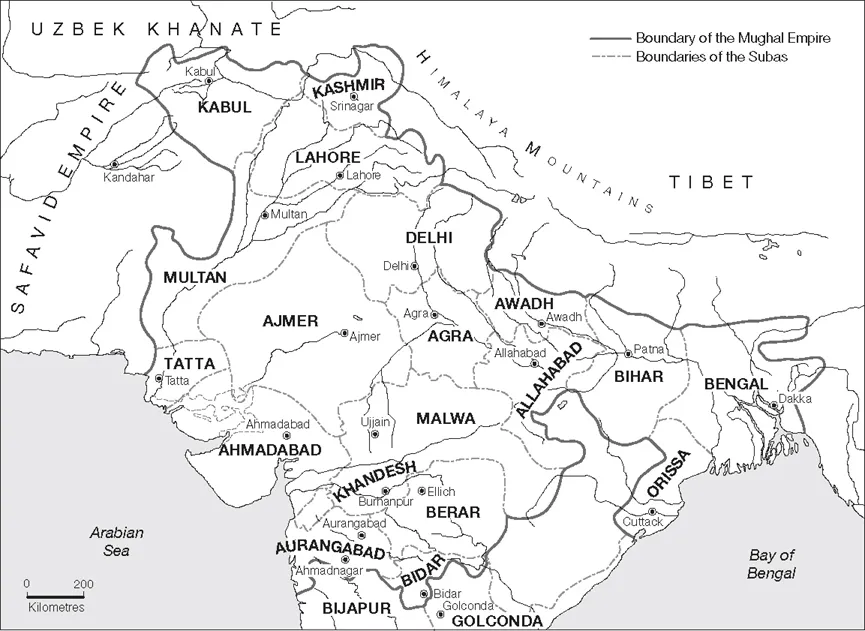

Large realms were the exception rather than the rule in South Asia. The Maurya Empire, under the rule of Ashoka (r. 268–233 BCE), was one such exception encompassing virtually the entire Indian subcontinent. Similarly, the Gupta Empire, between 320 and 500 CE, stretched across the whole of north India. The Mughal Empire, formed in 1525 by Babur (1483–1530), successfully conquered Delhi from Afghanistan and established the Timurid dynasty there. Its descendants built upon Babur’s foundation on which Akbar (r. 1556–1605) led the empire to its cultural flowering whilst Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707) brought the empire to its maximum territorial expansion. However, this expansion, both militarily and administratively, surpassed the organisational infrastructures of the central(ised) government. As a result, in the 1720s a number of provinces of the empire began to form new states. Some of these newly formed states, such as Awadh and Haiderabad, covered an area as large as the contemporary states of France or Spain, whilst others held proportions rather more similar to the size and importance of German principalities. Meanwhile, in Rohilkhand in the north and in Bhopal in central India, immigrant Afghan clans began to establish new dynasties whilst the Marathas were able to stretch their sphere of influence over large parts of central India.1

Much has been written concerning the causes of “decline of the Mughal Empire”. The bulk of this previous research can be summarised as follows:2 taking the death of Aurangzeb Alamgir as the starting point in 1707, a number of party struggles within the nobility of the Mughal court in Delhi were ignited, which, in the long term, questioned the central political power of the Timurid dynasty. Amid the power struggles between Turani and Sayyids and between the Rajputs and the Iranians, Aurangzeb, and his successors in particular, were unable to continue a balanced mediation between the different factions. A further reason for the disintegration of the Mughal Empire can be found in territorial expansion, which, in a large part, was led by Aurangzeb and which resulted in the impossibility to govern the empire and its provinces with the same intensity. Crises in the personnel and institutional system are also noted as reasons for the escalating de-territorialisation. The consequence of this disintegration within the administrative structure of the empire was an over-proportional growth of the empire’s nobility relative to territorial expansion. Their basic economic revenue, originating mainly from land revenue, no longer sufficed to fulfil the nobility’s obligations towards the maintenance of the Mughal cavalry units.

Map 1.1 Provinces (subas) of the Mughal Empire c. 1700

Coupled with these internal structural issues, the Mughal Empire was also under threat both externally (militarily) and internally (insurgent groups). Thus, the Afghan invasions of 1739, 1752–3 and 1759–61 – including the looting of Delhi and the expansion of the Marathas of Satara and Pune to Rajasthan – contributed to the long-lasting decline of central power in the Mughal Empire. Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in the famous battle of Panipat in 1761 between the Marathas and the Afghans as both expansionist military forces were tested to breaking point. Meanwhile, this development allowed the Sikh-rajas in the Panjab to declare independence from the Mughals whilst the East India Company (EIC) in Bengal and Bihar obtained administrative and political power after 1765. The empire’s political capacity at the end of the eighteenth century was but a shadow of its former glory. However, the capital city’s function as seat of legitimisation and the Mughal’s position as overlord were never doubted since none of the newly established dynasties declared independence from the Mughal Empire.3

A characteristic element of the transformation processes which the Mughal Empire underwent during the eighteenth century is not one of external collapse, but rather of internal crystallisation during the process of centralisation within the provinces. It is at this administrative level that the ideal type of a centralised state apparatus of the Mughals could be implemented as in the Subas Bengal and Awadh and the Maratha region, for example. State formation followed the cultural groundings of historical regions as in the case of Haiderabad, Awadh and Bengal. At the same time, the Mughal ruler and the Mughal’s residence became all the more important as they were increasingly regarded as being the source and origin of honour and dignity of the polity and of political legitimacy. Gradually, during the eighteenth century, a Mughal myth came into existence which became politically more binding than the Mughal’s former military and political dominance had been able to achieve. The British, as new provincial rulers, also lined up, if somewhat reluctantly, against the background of the sovereignty of the Mughals. Their empire ended de jure in 1858 with the British defeat of the Great Rebellion. Shared sovereignty which had prevailed and had strengthened throughout the eighteenth century was replaced by the European concepts of undivided sovereignty. As a result, the British finally halted the ongoing processes of state formation, and it was only the independence movement of the 1920s and 1930s that saw the emergence of a new Indian political will.4

The middle of the eighteenth century seems to mark a caesura in the political, as well as in the economic and social development of the Indian subcontinent. This is, for example, exemplified in the Battle of Panipat in 1761, which was fought between the invading Afghan forces under Ahmad Shah Abdali and an alliance of Maratha rulers as they each attempted to extend their own influence in the Panjab. This battle not only tested the military limits of the two expanding powers, but the Singhs, a Sikh noble family, also drove the faujdar (military governor) Ahmad Shah Abdali from Amritsar, uniting the territory between the Satlej and the Indus rivers under Sikh control. After the failed invasion by Afghan and Maratha forces, the Singhs declared independence from the Mughal Empire as well as from the Afghans in 1765. They expressed this point by acting as a sovereign ruler and henceforth began to mint their own coins.5 The new state obviously emerged out of the Mughal Empire and was therefore able to reform its administrative and military structures and to finally consolidate its territory of state.6

A year following the Battle of Baskar in 1764, fought between an alliance of Mughal and Awadhi forces on the one side and the joined forces of the EIC and the nawab of Bengal on the other, the EIC obtained the diwani of the Mughal provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa from Mughal Shah Alam II (r. 1759–1806). Shah Alamm II appointed the EIC the right to administer revenues and have jurisdiction over civil rights in the provinces and to forward a fixed part of the tax and revenue collections to the Mughals, since he regarded the EIC as a powerful and reliable contractor for the revenue collection in the east of his empire. The British henceforth began to construct and develop their idea of territorial rule in India, ushering in the beginnings of a “Modern India”.7 Expression of this still insecure and “fragile” position of the British in India was, at least until the 1790s, the debate about the continuity with the “ancient constitution” of the Mughal Empire, and the establishment in Bengal, in order to fit their own authority in the framework of legitimacy.8

This construction has been challenged by a critical historiography over the past decades, which can be observed in the critique towards the notion on the “decline of the Mughal Empire” and the emergence of the so-called “successor states”. None of the emerging states saw themselves as the succession in the wake of a sinking empire. Recent research has begun accentuating the long-term developments in order to present a more balanced overview of the state formation process. Such undertakings seek not only to make a link and find continuities with the Mughal Empire, but also to widen their lens of investigation further and take into account states such as the Vijayanagara Empire (1350– 1668). Simultaneously, such a construct of continuity does not come without its own inherent downfalls as the omnipresent danger of transcending once again into the trappings of creating a historiography in which unchangeability, and therefore an implied static state of South Asian history and society is given. Internal differences in the individual state formation process also need to be addressed and given just as much consideration as external developments.9

This revisionist approach generally accents a concentration of economic activities on the local level, which often went along with the intensification of the land-city relationship through the growing exchange of goods and labour. This “re-urbanisation” of the eighteenth century was made possible through the commercialisation of agricultural activities as observed in Bihar and Bengal, as well as in parts of Gujarat and in Mah...