![]()

CHAPTER 1

Beginnings: Multiple cinemas, multiple audiences, 1895–1907

Now playing

Vitascope debuts at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall, New York City, April 23, 1896

The playbill at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall on that Thursday night in spring 1896 was typical for a variety show of the period. A mix of music and theatrical performances featuring “Great Foreign Stars” – most notably the British singer and actor Albert Chevalier, who entertained the crowd with comic and sentimental songs as well as dramatic stories and humorous anecdotes – the line-up at Koster and Bial’s represented one of the dominant forms of popular entertainment at the turn of twentieth-century America. But there was a new addition to the playbill that night: the premiere of the latest innovation from the workshops of Thomas Edison, already the most famous inventor in America and a symbol of technological innovation and progress. Two strange machines, each with two turret-like lenses and covered in velvet to match the lush upholstery of the theater, were set up in the balcony.

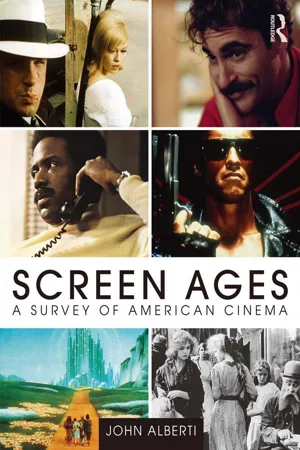

Fig 1.1

Edison’s Great Marvel. Source: Library of Congress.

As show time approached, a screen lowered from above, surrounded by a gilt frame. A reporter from the New York Times tells what happened next:

When the hall was darkened last night a buzzing and roaring were heard in the turret, and an unusually bright light fell upon the screen. Then came into view two precious blonde young persons of the variety stage, in pink and blue dresses, doing the umbrella dance with commendable celerity. Their motions were all clearly defined. When they vanished, a view of an angry surf breaking on a sandy beach near a stone pier amazed the spectators.1

A year before this performance, Americans had been introduced to the marvel of “moving pictures” through individual “peep show” viewers such as the Mutoscope and Edison’s own Kinetoscope, screen experiences limited to a single person at a time. Now, however, that solitary experience could be a social one, brightly lit on a large screen.

The short (very short – less than a minute each) films projected that evening displayed the same variety of “actualities” – brief glimpses of everyday scenes such as a busy city street, firemen at work, or a picturesque natural setting – that viewers had come to expect from the peep show viewers, along with the dancers described above, a comic boxing match, a scene from a popular stage play, and the “view of an angry surf breaking on a sandy beach near a stone pier” – “Rough Sea at Dover” by the pioneering British cinematographer Birt Acres. And if the Times reporter is to be believed, the Vitascope was a big hit:

For the spectator’s imagination filled the atmosphere with electricity, as sparks crackled around the swiftly moving, lifelike figures. So enthusiastic was the appreciation of the crowd long before this extraordinary exhibition was finished that vociferous cheering was heard. There were loud calls for Mr. Edison, but he made no response.

Before either the single viewer peep show machines or the first projectors appeared shortly before the turn of the twentieth century, audiences had never seen movies before. They had, however, been enjoying projected photographic images for almost half a century, mainly in the form of the “stereopticon,” or magic lantern, a device already familiar to vaudeville audiences that involved projecting photographs onto the same screens that now featured motion pictures. In fact, many stereopticon projectionists had developed various techniques for creating the illusion of movement on screen: moving images forward and back, superimposing multiple pictures, and other special effects. But nothing compared to the level of detail, excitement, and realism of the “Rough Seas at Dover,” whether viewed on the small screen of the peephole viewer or the big screen in at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall.

Fig 1.2

Thomas Edison with a prototype of his Vitascope projector. Source: Boyer/Getty Images.

A day at a Mutoscope peep show, St Louis, Missouri, 1900

The sign on the front of the building advertised the price of the attraction: “1¢.” Inside, patrons found rows of tall machines, each featuring a round, clamshell-shaped device with an eye viewer and a crank on the front. For their penny, customers would peer into the machine and turn the crank. Four years after the commercial introduction of projected moving pictures, the peepshow business was still going strong. Unlike projected movies, which were still usually shown as part of a variety show such as the one at Koster and Bial’s, where admission could cost a dollar or more (at a time when the average American income was still less than $500 a year), peep show machines were an entertainment option well within the budget of most people. The subject matter of most peep show movies resembled the line-up described in the newspaper story above. Some, however, contained more provocative (at least by the standards of the time) images: modern dancers, boxing matches (prize fighting was still illegal in all fifty states at the turn of the century), even the suggestion of peering through a keyhole at a woman changing her clothes.

Fig 1.3

A Mutoscope parlor at the corner of Olive and Leonard in Saint Louis shortly after the turn of the twentieth century. Source: Missouri History Museum.

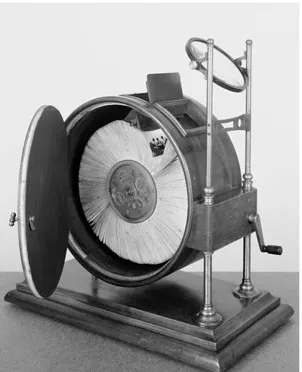

The machines in this St. Louis storefront parlor were Mutoscopes, single-viewer moving picture devices built by the American Biograph Company to compete with the Edison Company’s single-viewer Kinetoscope. While the Kinetoscope used the basic technology that would form the basis of movie projection until the digital age – an electric motor pulling a length of perforated film in front of a light bulb – the Mutoscope relied on a more ancient technology for creating the illusion of movement: the flipbook. The crank turned a wheel with dozens of stiff paper cards attached, each featuring a single photograph. As the machine flipped through each individual picture, viewers would have an experience of moving pictures. Although flipbooks were first sold as novelties in the mid-nineteenth century, the phenomenon of flipbook animation had been known for much longer. Even today, it remains a popular type of “do-it-yourself” moviemaking, as many a bored student with a textbook and a pen can attest. Just draw a series of simple pictures in the top corner of succeeding pages in the book, changing the position of each picture just slightly, and then ruffle the pages with your thumb. Instantly, you have your own version of the Mutoscope, and your own mini-movie.

The peep show machine challenges our contemporary ideas about what the experience of “going to the movies” means. There is no darkened theater, and while the viewing experience takes place in public, it is also extremely private, with each person at his or her own individual machine. The very name “peep show” that became attached to these machines stressed the potentially illicit quality of the experience, especially as flipbook machines later in the century increasingly lured viewers with the promise of “forbidden” images (a promise that – to escape local censorship laws – often proved greatly exaggerated).

Fig 1.4

The flip cards of the Mutoscope machine relied on older moving picture technology. Source: Science & Society Picture Library/Getty Images.

The Great Train Robbery plays at the Nickelodeon theater, Pittsburgh, 1905

Pittsburgh’s Nickelodeon theater, opened in 1904 by two local showmen and entrepreneurs, John P. Harris and his brother-in-law Harry Davis, represented the beginning of a new screen age in American movie history. For one thing, the Nickelodeon theater was devoted solely to the showing of moving pictures, one of the first of its kind in US movie history. In fact, for many years Harris and Davis’ theater was even thought to be the first all-movie theater in the country, and while that particular claim has come into dispute, the nickelodeon still represents an important evolution in American movie history.

The name of Harris and Davis’ theater-the “Nickelodeon” – was also the generic name given to the thousands of all-movie theaters that began to appear across the country at that time, a reference to their usual admission price of 5¢. Much less expensive than the vaudeville theaters, the nickelodeons attracted patrons from a broad spectrum of American society, including many working-class and immigrant viewers who hadn’t been able to afford projected moving pictures before.

Nickelodeons spread rapidly. By 1908, there were some 8,000 nickelodeons in the United States, and close to 14,000 less than a decade later. The arrival of the Nickelodeons signaled the growth of the movies into a major mass medium, no longer just one feature among many at a vaudeville show or an individual peep show attraction but a significant popular art form of its own, one that would contribute to the decline of the variety show circuits from which it arose.

The moving picture those patrons were paying a nickel to see that day in Pittsburgh – The Great Train Robbery – represented an even greater evolution in the screen experience of the movies. From the early actualities lasting less than a minute that defined the early screen age in America, the moviegoers in Pittsburgh watched a twelve-minute fictional narrative about a group of desperadoes who hijack a train. When locals learn of the crime, an exciting chase on horseback ensues, ending with a shootout in the woods and the recovery of the money. In what has become an iconic scene in American movie history, the movie concludes with one of its stars, Justus D. Barnes, pointing and shooting his gun directly at the movie audience.

Fig 1.5

The Waco Theatre in New York City was typical of the early storefront nickelodeon theaters. Source: The Kobal Collection.