This book brings together some of the work developed in a network of sociolinguistic research groups that have collaborated for several years, with ‘language and superdiversity’ as a broad thematic heading.1 This introduction sketches: (1) what we mean by ‘superdiversity’ and why we see it as a useful cover term; (2) key features of our approach and our collaboration; and (3) areas linked to superdiversity, where further work seems especially important (securitisation and surveillance).

Superdiversity: What and Why?

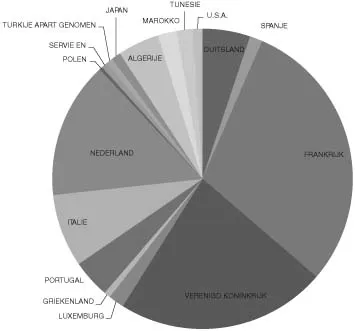

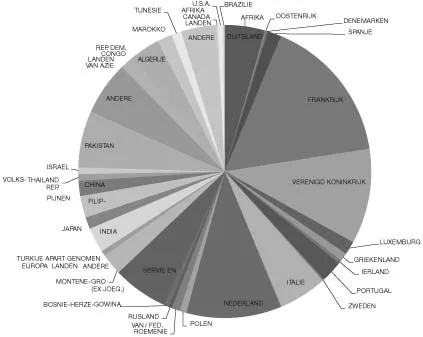

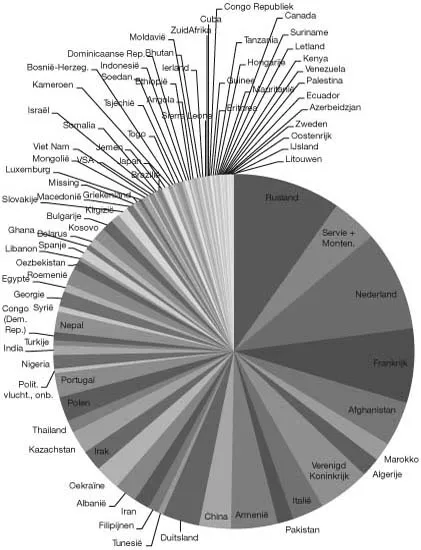

Over the past two and a half decades, the demographic, sociopolitical, cultural, and linguistic face of societies worldwide has been changing due to ever-expanding mobility and migration. This has been caused by economic globalisation and by major geopolitical shifts – the collapse and fragmentation of the Soviet communist bloc, China’s conversion to capitalism, India’s economic reforms, the ending of apartheid in South Africa. The effects are a dramatic increase in the demographic structure of the immigration centres of the world. These places are now no longer restricted to ‘global cities’ such as London or Los Angeles, but also include smaller provincial locations. The following charts show these evolutions in the Belgian coastal town of Ostend between 1990 and 2011 (Maly 2014).

The quantity of people migrating has steadily grown, the range of migrant-sending and migrant-receiving areas have increased, and there has been radical diversification not only in the socio-economic, cultural, religious, and linguistic profiles of the migrants, but also in their civil status, their educational or training background, and their migration trajectories, networks, and diasporic links. To capture all this, Steven Vertovec coined the term ‘superdiversity’:

Superdiversity: a term intended to underline a level and kind of complexity surpassing anything . . . previously experienced . . . a dynamic interplay of variables including country of origin, . . . migration channel, . . . legal status, . . . migrants’ human capital (particularly educational background), access to employment, . . . locality . . . and responses by local authorities, services providers and local residents.

(2007a: 3)

Figure 1.1 The population of Ostend, 1990

And whereas many accounts of global change post-1989 have focused on spatial and economic transformations and on national and ethnic groups moving across borders and boundaries, Vertovec sought closer attention to the human, cultural, and social intricacies of globalisation, often focusing on very specific migrant trajectories, identities, profiles, networking, status, training, and capacities.

In addition, faster and more mobile communication technologies and software infrastructures have affected the lives of diaspora communities of all kinds (old and new, black and white, imperial, trade, labour, etc. [cf. Cohen 1997]). While emigration used to mean real separation between the emigré and his/her home society, involving the loss or dramatic reduction of social, cultural, and political roles and impact there, emigrants and dispersed communities now have the potential to retain an active connection by means of an elaborate set of long-distance communication technologies. These technologies impact on sedentary ‘host’ communities as well, with people getting involved in transnational networks that offer potentially altered forms of identity, community formation, and cooperation (Baron 2008).

There is, of course, a very large, rich, and wide-ranging literature covering contemporary social change,2 and this raises the question: Why choose ‘superdiversity’ as a cover term for the social processes studied in a book about language? Our answer is as follows.

Figure 1.2 The population of Ostend, 2000

When compared with the range of other terms on offer – for example, ‘translocality’ (Greiner & Sakdapolrak 2013), ‘liquid modernity’ (Bauman 2000), or ‘global complexity’ (Urry 2003) – Vertovec’s ‘superdiversity’ comes across as a primarily descriptive concept, limited in ‘grand narrative’ ambitions or explicit theoretical claims, committed instead to ethnography (see Vertovec 2009). It spotlights the ‘diversification of diversity’ as a process to be investigated but it doesn’t pin any particular explanation onto this. Indeed, the term ‘superdiversity’ is itself relatively unspectacular – ‘super’ implies complications and some need for rethinking, but ‘diversity’ aligns with a set of rather long-standing discourses. Proposing change while invoking continuity like this, there is nothing very radical or dramatic here. But this has two advantages.

Figure 1.3 The population of Ostend, 2011

First, it gives the term strategic purchase in the field of social policy. In the “normative discourses, institutional structures, policies and practices in business, public sector agencies, the military, universities and professions” (Vertovec 2012: 287), the word ‘diversity’ has very considerable currency. Superdiversity goes beyond this and points to major problems facing traditional multicultural understandings of diversity – social categorisation has itself become a huge challenge for policy and politics, and according to Kenneth Prewitt, former Director of the US Census Bureau:

classification is now a moving target. [There are] two possible outcomes: either a push toward measurement (like censuses) using ever more finely-grained classifications, or system collapse – the end of measurements of difference. In either case, . . . it is increasingly doubtful that policies aimed at making America more inclusive will centre, as they did in the 1970s, on numerical remedies using statistical disparities as evidence of discrimination.

(reported by Vertovec 2012: 303–304)

But in suggesting change with continuity instead of radical overturn, Vertovec’s formulation makes it easier for policy to embrace these issues,3 and its effectiveness is evident in its adoption in a wide range of different local government arenas (e.g. Amsterdam, Birmingham, Frankfurt, Ghent). Of course, this adoption is itself a complex process deserving close critical analysis, as Arnaut emphasises in his contribution to the collection, and there is much more involved than just an authentication of civic diversity.4 Even so, the capacity to engage with local political and institutional discourse is important for the research covered in this volume, and in this respect superdiversity is a useful banner. It offers “an awareness that a lot of what used to be qualified as ‘exceptional’, ‘aberrant’, ‘deviant’ or ‘unusual’ in language and its use by people, is in actual fact quite normal” (Blommaert 2015: 2, emphasis in the original).

Second, for sociolinguistics itself, it is also fitting that superdiversity marks a shift of footing without disconnecting from what went before – a desire for synthesis rather than for a new sub-discipline. Diversity has been a central concern in sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology for much of the twentieth century, both as the focus for empirical description and as a political commitment: “[d]iversity of speech has been singled out as the main focus of sociolinguistics” (Hymes 1972: 38; see also e.g. Boas 1912). Furthermore, sociolinguists are now very familiar with the problems of group identification and the critiques of essentialism that give superdiversity much of its relevance. In 1969, Dell Hymes called the idea of discrete sociolinguistic groups into question when he said that “the relationship of cultures and communities in the world today is dominantly one of reintegration within complex units” (1969 [1999]: 32), and 20 years later Mary Louise Pratt reiterated this in the deconstruction of what she called the ‘utopian linguistics of community’, proposing a ‘linguistics of contact’ in its place (1987, emphasis in the original). Indeed, terms such as ‘hybridity’, ‘heteroglossia’, and ‘fluidity’ proliferate in the contemporary sociolinguistic and linguistic anthropological literature. But as an encapsulation of these concerns, ‘superdiversity’ not only has greater currency in public policy discourse, but is also often associated with an interrogative stance, openly proposing that new forms of understanding are now needed to make sense of the contemporary social landscape (e.g. Fanshawe & Sriskandarajah 2010). Well-established social categorisations are now being challenged, the argument runs, along with the macro-theories and models of society built around them, and in their place superdiversity calls for meso- and micro-scale accounts, focusing on lower levels of social organisation. So here we hear calls for social scientists to turn their attention to informal processes, seeking new principles for social cohesion in local ‘conviviality’ and low-key ‘civility’ (Gilroy 2006; Vertovec 2007a; Wetherell 2010). For sociolinguists, who specialise in the rigorous and disciplined description of smaller-scale processes such as these, this sounds like a summons, and the challenge to traditional sociological analysis potentially ends up enlarging the agenda of linguistics.

Of course, if it is correct that more of the responsibility for producing plausible descriptions of contemporary cultural processes now falls to disciplines such as sociolinguistics, we need to double-check that our apparatus is actually equal to the role. Blommaert and Rampton start to do this in their opening chapter, and they begin their review of the sociolinguistic instrumentarium by invoking “the pioneering work of linguistic anthropologists such as John Gumperz, Dell Hymes and Michael Silverstein [starting in the 1960s, as well as] the foundational rethinking of social and cultural theorists such as Bakhtin, Bourdieu, Foucault, Goffman, Hall, and Williams.” They go on to say that “with this kind of pedigree, ‘robust and well-established orthodoxy’ might seem more apt as a characterisation of these ideas than ‘paradigm shift’ or ‘developments’.” But contemporary conditions have repositioned and intensified the relevance of this apparatus, and once again the encapsulation of both continuity and change in ‘superdiversity’ seems particularly apposite. Everyone in sociolinguistics is familiar with ‘diversity’, but ‘super’ signals something more, requiring a retuning or realignment of parts of the machinery, sometimes even the shaping and development of new elements. So in signalling selective renovation rather than wholesale reinvention in this way, ‘language and superdiversity’ is an apt and indeed rather parsimonious reformulation of the sociolinguistic enterprise, adjusting it to new times.

So what can the ‘sociolinguistic enterprise’ be expected to look like in a book with ‘language and superdiversity’ in the title?