![]()

1

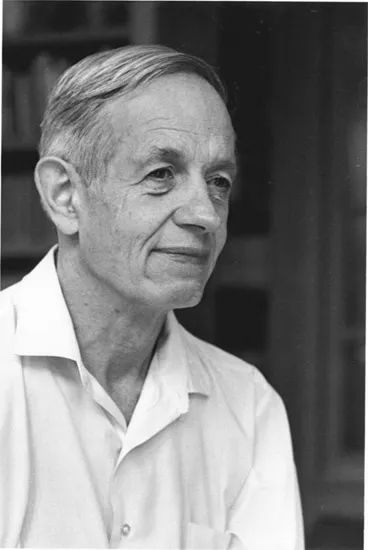

John Nash

Reason’s approach to an alternative reality

Murray Jackson

The remarkable story of John Nash, Nobel Laureate, has received worldwide publicity through the success of Sylvia Nasar’s biography A Beautiful Mind (Nasar 1998) and the film of the same name derived from it (Howard 2001). In 1958, at the age of 30, already recognized as a mathematician of genius, Nash began to suffer recurring psychotic states from which he recovered 25 years later. This chapter will explore the nature of Nash’s illness from a psychoanalytic perspective, based on the public accounts of his life. Included will be a discussion of both the different factors that may have precipitated his move into psychotic thinking and those experiences which may have enabled Nash to take the steps necessary for his eventual recovery. Certain features of Nash’s life, which are not explored in either the book or the film, have important implications for the treatment of people suffering from severe psychotic illness and these will be reflected upon in this chapter. The aim of this chapter is to illustrate how modern psychoanalytic concepts can contribute in a helpful and practical way to the psychotherapeutic treatment of people suffering from psychosis and other related problems.

The chief sources of information for this chapter are Sylvia Nasar’s biography (Nasar 1998), Nash’s own writing subsequent to his recovery, and his 1996 historical lecture in Madrid. The film A Beautiful Mind (Howard 2001) is also of considerable interest. Nash cooperated more extensively in the making of a later documentary The American Experience: A Brilliant Madness (Samels 2003) which adds further significant material. Nash’s personal disclosures during and after his illness also corroborate much of the information included in this chapter.

Prologue

Nash came to understand his illness as an essentially psychogenic one, a view contrasting sharply with the reductionist ‘biomedical’ orientation of the biography and of much of contemporary psychiatry. The film script of A Beautiful Mind (Howard 2001) shows a certain acquaintance with psychoanalytic theory; for instance, it refers to Rosenfeld’s ‘destructive narcissism’ (Rosenfeld 1971: 169–178). Nevertheless, it draws the same biomedical conclusion as the biography. Apparently, in the interests of opposing the social stigma attached to psychosis, the film promotes the seriously misleading message that psychosis is an organic illness like diabetes.

Nasar’s biography (1998) describes Nash’s colleague questioning him in a reasonable moment, soon after the acute onset of his psychosis: ‘How could you, a mathematician, a man devoted to reason and logical proof, believe that extraterrestrials are sending you messages? How could you believe that you are being recruited by aliens from outer space to save the world?’

Nash replied: ‘Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me in the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously’ (Nasar 1998: 11).

Nash’s remarkable response demonstrates how unconscious mental processes underlying both creative and psychotic phenomena can lead to a loss of the capacity to distinguish between the two. His response might also suggest that Nash had an unusual ability to preserve the capacity for curiosity and intellectual exploration, a talent which may have served him well throughout his illness and contributed to his eventual recovery.

Why study John Nash?

All the psychological factors that will be considered in this essay are very familiar to modern-day psychoanalysts working with people suffering from psychosis, and such psychological descriptions can be found in psychoanalytic publications. For example, good clinical illustrations of successful psychotherapy with people suffering from psychotic states exist in Jackson and Williams (1994), Robbins (1993) and Lotterman (1996 and 2015 in press). Although Nash’s recovery after such a long psychotic illness is not unusual (Bleuler 1978; Harding et al. 1987) there are features that make Nash’s case exceptionally interesting to discuss. For example:

- the worldwide publicity arising from the award-winning film, A BeautifulMind (Howard 2001), and its partial misrepresentation of the nature of psychotic states;

- Nash’s remarkably high level of abstract thinking that led many of his peers to regard him as the greatest mathematician of the century;

- the fact that, upon recovery, Nash was able to resume creative work of a high order;

- Nash’s considered decision to reject the anti-psychotic medication which had been effective in suppressing his symptoms, and his insistence that he find a way of recovering through his own efforts;

- the likelihood that a significant benign transformation and growth of Nash’s immature personality occurred as a consequence of his attempt to work through some of his pathogenic unconscious conflicts.

Background history

For those who have not read the book, much of this history is contained in A Beautiful Mind (Nasar 1998). Born in 1928, Nash was a loved and wanted first child who was followed, two years later, by his sister, Martha. He was described as ‘a singular little boy who was solitary and very introverted’ (O’Connor and Robertson 2002: 7). Nash’s mother and father were devoted and loving parents of exceptional intellectual stature, who unreservedly supported the development of their son’s prodigious intellectual qualities and enquiring mind. Nash pursued his education mainly at home through encyclopaedias, science books and making scientific experiments. He was bored by the teachers at school and learning at school was troublesome because of Nash’s marked disrespect for authority and his conflicts with his peers.

From early childhood onwards Nash’s peer relationships were fraught with hostility. A contributory factor may have been his intense destructive jealousy towards his sister Martha, whom he once seated in a chair which he had wired up with batteries (O’Connor and Robertson 2002: 2). Nash often derived malicious pleasure by playing childish, sometimes cruel, tricks on his peers. Torturing animals and creating an explosion that badly hurt a classmate, as well as drawing antagonistic caricatures of his classmates, suggested Nash had an excess of un-integrated hostility to peers and to his sister, of whom he speaks very little. Few friendships resulted from Nash’s eccentric, withdrawn behaviour and his underlying aggression.

At 14, Nash became particularly inspired by E. T. Bell’s Men of Mathematics (1937) and he tried on his own to solve the mathematic problems presented in Bell’s book. Nash had a strong competitive tendency to present himself as an unrivalled and superior thinker who denounced the work of others in his field. His arrogance and eccentricity were most pronounced in his early adult life. As a result he was often tormented by his contemporaries.

Aged 19, Nash burst onto the mathematical scene and over the next ten years established himself as one of the more remarkable mathematicians of the century. His ground-breaking work into the processes of human rivalry and his theory of rational conflict and cooperation are achievements which have sometimes been regarded in mathematical circles as having similar stature and importance to the ideas of Newton and Darwin. Nash worked for some years as a part-time consultant to the RAND Corporation, a privately funded ‘think-tank’ employed by the US military during the Cold War period. This post brought him into a certain, although limited, contact with the Central Intelligence Agency. At this time, US concern about Soviet nuclear development had a markedly paranoid quality, which found its most direct expression in the anti-communist activities of the ‘McCarthy era’. A pre-emptive US military strike was being seriously considered (Milnor 1998). Simultaneously, Nash’s ‘game theory’ was being seen as crucial to Cold War politics.

In 1951, Nash, aged 23, began a close and intense relationship lasting over several years with a colleague, ‘Mr Jacob B’ (Nasar 1998: 180). Nasar makes the interesting suggestion that it was Mr B’s reciprocation of Nash’s love which altered Nash’s perception of himself in a fundamental and benign way (Nasar 1998: 181). During this period he also conducted a relationship with a young, attractive nurse, Eleonor, who became his mistress. Shortly afterwards, while continuing his affair with Eleonor, he became involved in a relationship with his future wife, Alicia. In 1954, Nash’s involvement with the RAND ‘think-tank’ came to an abrupt and humiliating end when he was arrested and charged with engaging in homosexual behaviour in public.

In 1954, around the time of this traumatic event, Eleonor became pregnant and gave birth to their son, John. For several years Nash kept ongoing life with Eleonor and John almost completely secret, maintaining it together with this longstanding and emotionally powerful relationship with his male colleague, ‘Mr B’. Subsequently, Nash was filled shame when Eleonor shocked his parents with news of their affair and child. A further consequence of the exposure of his double life was that Nash’s parents, horrified at his duplicity, at first pressed him to marry his mistress (Nasar 1998: 206). Nash father died in 1956 shortly after hearing of Nash’s double life.

It was against the background of these personal and professional conflicts that in 1958 Nash, while continuing his affair with Eleonor, now married Alice, a physicist and former student. Eleonor was furious with him for rejecting her. Nash’s wife quickly became pregnant in the context of all this turmoil. Nash thereupon abandoned his mistress and declined to give financial help to her and his son. This resulted in their suffering considerable financial hardship during his son’s childhood. Shocked by what he regarded as Nash’s ‘callousness’ towards Eleonor, and finding the threesome relationship too intense, ‘Mr B’ terminated his involvement with Nash, leaving Nash suffering an overwhelming sense of rejection. In 1959, Alicia, gave birth to their baby, named John; the same name as Nash’s firstborn son conceived with Eleonor.

The biographer’s views

Sylvia Nasar’s book (Nasar 1998) is a masterpiece of meticulous research and of skilful and indefatigable, albeit intrusive, interviewing. Her biography was unauthorized, and because Nash declined to disclose any personal information that might cause embarrassment, the depth of Nasar’s (1998) investigation was, of necessity, limited. Nonetheless, her perceptiveness is evident in her conclusions about the nature of Nash’s vulnerability and her understanding of the factors precipitating his breakdown. She considers that his extraordinary sense of self-importance had its roots in his early childhood, and was a way of protecting himself from a sense of loneliness, isolation, jealousy and hostility, while at the same time obscuring his craving for love and affection.

Nasar (1998) suggests that Nash’s impressively intellectual mother might have been excessively ambitious for Nash and thus possibly experienced by him as intrusively demanding in her educational endeavours with him. At the same time his father, a somewhat reserved, highly intelligent and scientifically minded man, might have been experienced as emotionally unavailable at important stages of Nash’s development. When she searched through the historical information regarding Nash’s parents and grandparents, Nasar (1998) could find no evidence of trans-generational pathological influences.

As well as acknowledging the importance of Nash’s personal life experiences, Nasar (1998) lends great importance to the fact that, shortly before his breakdown, Nash had narrowly failed to win the Fields medal, the most prestigious prize for mathematics, to which he felt entitled. Nash had been shocked to discover that some months before he solved a crucial problem in mathematics, a rival had already resolved it. Retrospectively, Nash said that he believed that his rival’s earlier resolution of the mathematical problem was the reason why the Fields medal had eluded him. Nasar (1998) considered Nash’s setback to be an Icarus-like fall, combined with new emotional burdens occasioned by marriage, revelation of his affair and his parenthood, coupled with the death of his father. The cumulative effect of these factors interacting with his own internal experiences seemed to contribute to his psychotic states (Nasar 1998: 221). Nasar’s (1998) uncontroversial conclusion leaves open such questions as the nature of Nash’s pre-morbid vulnerability and the meaning of his psychotic experiences. Her omissions reflect the stance of well-known, primarily biomedically oriented psychiatrist-researchers who discredited psychoanalysis as a method of treating psychosis and maintained that psychosis is simply a brain disease, albeit with psychological concomitants (Nasar 1994).

The film: A Beautiful Mind

The film script, A Beautiful Mind, was written by Avika Goldsman, directed by Brian Gazer and produced by Ron Howard (2001). The film-makers set out to involve the audience in Nash’s experience, inviting them to empathize with him, hoping in this way to contribute to the de-stigmatization of mental illness and to raise public awareness of the very often terrifying nature of his type of psychosis. The film-makers dramatically illustrate what it can be like to experience the invasion of the mind by alien forces and to lose the capacity to distinguish a hallucination from reality. The viewer also has the opportunity of experiencing Nash’s confusion and perplexity by means of the director’s device, explained in detail in the accompanying DVD, of offering many subtle clues which point to the fact that what is being seen is Nash’s delusional reality.

The film-makers have created a remarkably authentic presentation of some of the important aspects of the inner life of Nash and many other people suffering from psychosis. The film’s imaginative elaboration of Nash’s dream-like psychotic experience is, in some respects, psychoanalytically sophisticated. The scriptwriter creates an imaginary companion, Charles, who at first gives him constructive encouragement, but eventually incites him with great seductive power to grandiosity and omnipotent thinking, thereby undermining Nash’s sense of reality. The scriptwriter also invents a hallucinatory Mafia-like controller/supervisor of the CIA, William, who eventually reveals his sadistic potential and threatens to kill Nash and his wife and child if he tries to break free of the grip of the CIA ‘gang’. Nash eventually courageously struggles to escape from William and the murderous gang’s powerful and threatening influence.

These themes of being potentially protected and then powerfully coerced by compelling delusions are particularly well-documented in Kleinian psychoanalytic studies of psychotic conditions (Rosenfeld 1987; Steiner 1993b; De Masi 1997; Jackson 2001). The destructive delusional organization, described by Rosenfeld (1987), lends meaning to the narcissistic omnipotent object relations characteristic of certain psychotic states of mind. In his book Impasse and Interpretation, Rosenfeld (1987) describes the nature of narcissistic omnipotent object relations. He suggests that a narcissistic character structure arises in infancy as a protection against the sense of helplessness but subsequently such a character structure may lead to many pathogenic consequences. Rosenfeld goes on further to explain that:

Once a firm narcissistic way of living has been established beyond infancy, relations to self and object will be controlled in order to try to maintain the delusional omnipotent belief. Any contact with reality or self-observation inevitably threatens this state of affairs and is felt as very dangerous … this omnipotent way of existing is experienced and even personified as a good friend or guru who uses powerful suggestions and propaganda to maintain the status quo, a process which is generally silent and often creates confusion. Any object, particularly the analyst, who helps the patient to face the reality of his need and dependence is experienced as dangerous by this good friend, who is afraid of being exposed as a phantom.

When the patient’s capacity for self-observation improves … and he tries to free himself from being controlled, the persuasive, seductive nature of the omnipotent structure changes: it becomes sadistic and threatens the patient with death. Only then does one become aware that hidden in the omnipotent structure there exists a very primitive superego, which belittles and attacks the patient’s capacities, observations, and particularly the acceptance of his need for real objects. The most confusing element in this process is the successful disguise of the omnipotent structure of omnipotent relating and the envious destructive superego as benevolent figures; this disguise makes the patient feel guilty and ungrateful towards them when he tries to improve.

(Rosenfeld 1987: 87)

The scriptwriter’s psychoanalytically sophisticated interpretation of Nash’s inner object relationships can fairly be considered as a brilliant depiction...