![]()

1 | Population and development: the core issues in historical perspective |

This chapter provides:

introduction to the language and basic ideas of Population Studies and of Development Studies, and the relationships between them;

global review of how and why have population growth and development been linked in the past, and especially in the last 250 years of rising rates of world population growth and rapid development;

region-specific discussions of population growth and development relationships for the major continental regions of the world;

an identification of the wide range of circumstances in which population/development relationships have been worked out.

At its core the relationship between population and development is primarily, though not exclusively, an economic one. It is about the aggregate consumption and production of resources, and the balance between consumption and production. Populations consume ‘resources’. These may be food or energy or other naturally occurring resources, as well as other ‘resources’, such as the cultural resources created by societies and/or provided by the government, such as schools or hospitals or roads. The economy concerns the production of all these resources. The essence of ‘development’ has been that this resource base has been consistently expanding. Globally, there is now more food and energy being produced than ever before. More people are attending schools or have access to medical care than ever before. However, the population has also been growing. The more people there are, the greater the resource base needs to be if average consumption levels are to be sustained. Per capita production (the average amount of any resource available per person in the population), and not merely gross production, needs to be sustained where there is population growth.

Where the number of people is growing, the normal expectation is that additional resources will be sought to at least sustain the population at these same per capita levels. Each additional person means that there will be more people to work to create and manage these resources – as farmers, or miners, or teachers or doctors – as well as to consume them. Thus population growth becomes identified as a critical problem for development, for production as well as for consumption. People are hands to work as well as mouths to feed! The historical experience has been that there has been a growth in consumption, that is, population growth, as well as a growth of production, that is, development, and that population growth and development have occurred together. Generally the per capita growth in production has exceeded the per capita growth in consumption. Thus global levels of living have been rising over many centuries, but most rapidly and more obviously during the last two centuries. Yet such a positive historical experience of per capita development being greater than population growth may not necessarily apply to all populations at all time periods. The conditions under which there can be per capita consumption that increases or declines with population growth are central to the concerns of this book.

The reflexive relationships between population and development have always been important for human groups. The earliest hunter-gatherer societies were limited both by their population size – small groups living at low densities – and also by their low levels of well-being and their limited prospects for any economic change. These populations lived at a minimum subsistence level with very low levels of technology. They could not grow too large or too rapidly, otherwise the groups would be unable to support themselves from local resources of fruits and animals. Development was therefore limited for these populations, not only by the technology but also by the relatively few people available to manage and harvest any available local resources. There was typically a shortage of people. Rapid population growth was restricted by very high mortality associated with recurring famines and diseases, even though fertility might have been high. Life was generally nasty, brutish and short.

With the coming of settled agriculture, the so-called Neolithic Revolution of about 8000–10,000 BP, populations could grow because there was more food available as a result of the new forms of agricultural production. Settled agriculture meant better control of basic resources, including soil and water, to increase production per unit of settled area. This was most obvious with greater control of water, as in the hydraulic civilisations of the Nile in Egypt, the Tigris–Euphrates in Babylon/Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and the Indus in modern Pakistan. However, population growth in these civilisations was constrained by the relatively small areas where the new technologies could be developed, and by relatively limited exchange of goods, including food, and ideas between the populations of surrounding areas of these more developed regions. It was also limited by new disease regimes and new risks of higher mortality associated with more crowded living conditions. There were new forms of social control in these more organised kingdoms and empires, often with towns, and with differentiated cultures that may have affected fertility and reproductive behaviour. Population was now subject to rather different controls on births and deaths, but these still seemed to support high mortality regimes as well as high fertility. Low levels of technology and food security together with high levels of poverty and recurring disease epidemics limited the scope for long-term population growth and long-term development.

Modern industrial societies, by contrast, are characterised by large numbers of people living at high levels of development. People on average have high incomes, use sophisticated technologies and are supported by exchange within and between large-scale societies across the globe. Movement of goods, people and ideas is relatively easy, and has been consistently becoming easier. People and technology together contribute to the broader processes of development. Globally the rapid growth in world population of the last 300 years, since about 1700, has been more than matched by rising incomes, by increases in food production and by improvements in food security. There has been a sharp reduction in the number as well as the intensity of local as well as regional famines. Unprecedentedly rapid population growth has occurred at the same time as unprecedentedly rapid economic development and social change have emerged as dominating global phenomena of the modern era.

However, a growing gap between rich and poor regions of the world is all too evident. Within an increasingly globalised world system there are now even sharper economic inequalities between – and also usually within – populations than there have ever been. We see this most obviously between the rich and the poor world, between the Global North and the Global South, and the width of the gap is a matter of continuous political discussion and public information. Global development has not brought improved livelihoods to all populations. Nor has it eliminated famines, hunger and poverty. There is abundant food and other resources for some populations; there is abject poverty and shortage of resources for others. For some societies population growth seems to have been a valuable and necessary positive accompaniment to economic growth – most obviously in a country such as the United States of America, now the richest, most technologically advanced country in the world. During most of the nearly two and a half centuries since independence in 1776, and before that as a series of colonies, the US has been a country characterised by population growth in which the migration component of growth has greatly exceeded natural growth for most of the time. By contrast, population growth may have constituted an immediate and also a long-term threat to life and livelihoods in some other societies. This now seems most apparent in South Asia and Africa – now the poorest regions of the world – with rapidly growing populations in the last 100 years and some areas of very high population density in areas of greatest impoverishment.

This opening chapter describes the long-term nature and patterns of both population growth and development, each taken separately. It focuses first at the global scale, then at the continental scale to explore the rather different kinds of patterns and relationships that have been apparent in different parts of the world. What are the conditions under which population growth has seemed to act as a constraint on development, both in the past and at the present time? This discussion will provide the essential empirical baseline for reviewing the variable geography of population/development relationships. Chapters 2 and 3 will then explore the key ideas and models that have been promulgated to address the core analytical questions about these experiences of the population/development relationship.

Global population change

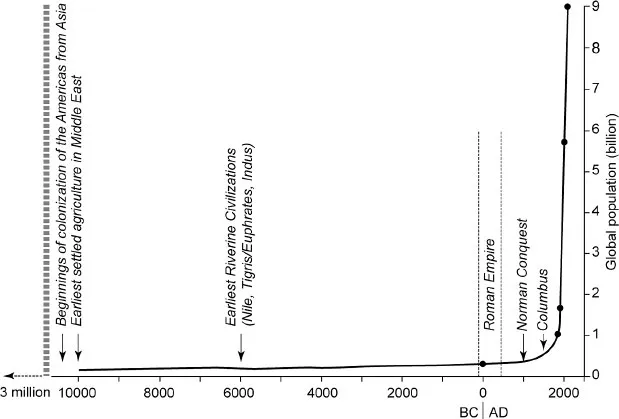

The global population was estimated by the UN to be 7.25 billion in 2014 (United Nations 2014b), but this large size is a very recent phenomenon. As Figure 1.1 shows, for most of human history (that is, stretching back for perhaps 3 million years – 3000 millennia) the population has been much smaller, reaching 1 billion only in about 1820, less than 200 years ago. Only two millennia ago, at about the time of Christ and the Roman Empire in Western Europe, West Asia and North Africa, it was probably only half that, at about 500 million. Before that there had been a very long period of very slow and probably fluctuating growth in which, over the long term, births had only very slightly exceeded deaths (Livi-Bacci 2012).

Figure 1.1 World population growth over 12 millennia.

However, within this long period of very slow growth there were probably in most regions many short periods – of only one year or perhaps a generation – of absolute decline, associated with famine or disease. Some of the declines were known to have been spectacular, as in the bubonic plague epidemic, the Black Death, of the mid-fourteenth century, that spread very rapidly throughout the Mediterranean lands and Western Europe and parts of South and East Asia and may have resulted in the deaths of about one-third of their populations over a five-year period (Noymer 2007). The nearest twentieth century equivalents, but a long way from its scale of mortality, have been the global influenza pandemic of 1918/1919 and the HIV/AIDS pandemic from 1981. As many as 30 million people died of the earlier Asian influenza epidemic (more than three times as many as were killed in the First World War), but this amounted to less than 1 per cent of the world population at that time. Even in the worst affected regions in Africa and South Asia it was probably never more than 5 per cent of that population (Langford 2005). HIV/AIDS, recently the major global epidemic threat, has been likened to the Black Death, with an estimated 35 million people having died of AIDS globally since 1981. Although the numbers dying of AIDS had been falling in recent years (from a peak of 2.3 million in 2005 to 1.6 million in 2012), the numbers infected has been continuing to grow (estimated at 35.3 million people living with HIV infections in 2013) even though the roll-out of antiviral therapies has been successful in reducing AIDS mortality (UNAIDS 2013). The global epidemic shows little sign of slowing or running out, though there have been declines in HIV prevalence in some world regions. The most pessimistic scenarios for the most affected areas in Southern Africa had been, but are no longer, for population declines in a few countries (Botswana, Swaziland, South Africa) by the mid-twenty-first century, but even there not on the scale of the Black Death for large regions. HIV/AIDS, as we shall see (Chapter 4), is a truly exceptional epidemic disease, but it is now clear that pessimistic scenarios that were discussed in the 1990s now seem seriously exaggerated for other continents and even for the worst-affected countries of Southern Africa (Caldwell 2006).

More typically, however, at the end of any millennium the population was probably never more than 5 per cent greater than it had been at the beginning of that millennium, and may even have been smaller. During most of human history life expectancies at birth were probably about 30–35 years, which may be compared with about 40 years in most of the poorest populations in the world today (that is, pre-AIDS; this recent epidemic briefly brought life expectancies in the 1990s below 40 in some of the most affected countries). In the absence of systematic medical knowledge, but in periods of nutritional fluctuation with many years of absolute food deficits that were and still are characteristic of hunter-gatherer societies, survival rates for children and adults were likely to have been very low. As food supply became more secure with settled agriculture, initially in the riparian, hydraulic civilisations of the Middle East and the rice civilisations of South Asia and China, it is likely that long-term mortality levels improved, though there were still seasonal fluctuations with longer term famines and excess famine mortality. But there was still no systematic control of disease, now much more likely to be spread as population densities rose, and people then came into greater contagious and infectious contact with others. They were also more exposed in these water-based cultures to water-borne diseases, such as dysentery and typhoid, and habitats of insect vectors for disease such as malaria. Mortality remained high despite improved food security.

Birth rates, on the other hand, were also high, probably with an average of about five live births per woman over her lifetime, which is much the same as in the contemporary populations of highest fertility. However, fertility was not subject to similar rapid short-term fluctuations to the extent that mortality could be, for it was more controlled by social norms within marriage and cultural norms such as breastfeeding patterns as well as by basic biology, all relatively constant in any social realm. In theory, women can complete perhaps 20 full-term pregnancies during their reproductive period from menarche at about 13–15 years to menopause at 45–60 years. The highest recorded mean fertilities of whole groups are between 12 and 14 children per woman, and these are exceptional. Usually some 3–5 per cent of women in any population are biologically infertile, and this may rise for the further and much more variable proportion of women made infertile as a result of disease, especially sexually transmitted disease. There are also short periods of a few months of inability to ovulate and conceive immediately after childbirth. These biologically infertile periods are extended by social constraints on fertility, mostly associated with marriage and sexual abstinence before, during and after marriage. Biological and social constraints, together identified as the ‘proximate determinants of fertility’ (see Chapter 5), mean that humans do not breed to their maximum potential, but at levels far below it. Most women normally had between about four and eight children per woman in prehistoric and historical populations (Lee and Wang Feng 1999).

With early marriage, that is where most women are married by the time they are 20 and some even before menarche, as in contemporary South Asia, there is potentially a long period of ‘risk’ of pregnancy, but normally birth intervals are long. Extended intervals between births are typically associated with long periods of breastfeeding, which are beneficial for the health of mothers as well as their babies. However, age at marriage does vary from one population to another, and may change over the long term within populations. This may result in some long-term fluctuations in fertility. In England between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, it is known that fertility rose overall, largely as a result of earlier marriage associated with periods of relative prosperity, but that rise was small – less than one child per woman; no more than a maximum of 20 per cent over a century – but normally much less (Wrigley and Schofield 1981).

Although it is not usually possible to reconstruct directly the demographic balance for any given period of population, normally mortality has fluctuated much more than fertility. The net long-term effect has been to produce very slow long-term growth. A ‘natural’ fertility regime, with birth intervals controlled solely by biology, has not been apparent in any population, and both fertility and mortality seem to have been underpinned by social institutions and economic and political systems to produce this slow population growth. Whatever growth there was could be, and usually was, incorporated with the existing land area and local resource base, for example in early riverine civilisations, with associated rising population densities. It could also fuel migrations into new lands and pastures to prevent raising population densities in the source areas of the growth, and populations spread to new areas of settlement. Human populations in the past, even more t...