Introduction

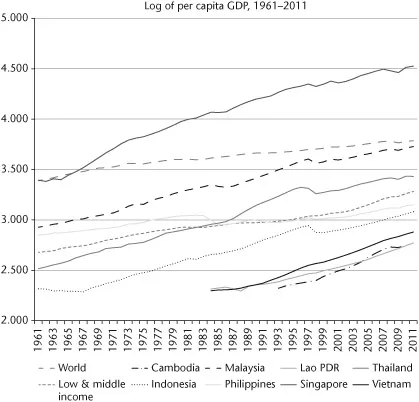

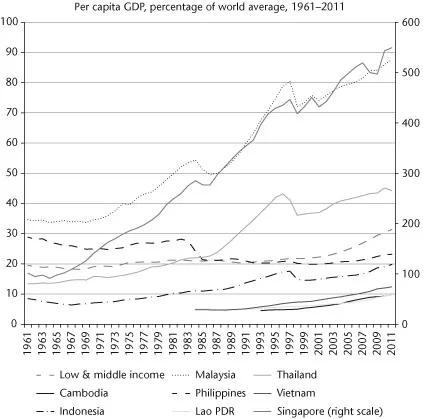

As of 2014 Southeast Asia is home to 620 million people, or 8.6 percent of world population. Its six large economies (Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam) and five smaller ones (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Brunei, and East Timor) together account for one-tenth of the income generated in all low- and middle-income economies worldwide. Less than two generations ago the vast majority of Southeast Asians were very poor. Since the 1980s, however, the region as a whole has achieved and sustained a remarkable rate of growth (Figure 1.1), in the course of which tens of millions of its citizens have successfully escaped severe poverty. This growth experience sets the region as a whole apart from other developing areas (only China can claim a consistently higher growth rate of per capita gross domestic product [GDP]) and has seen incomes in most Southeast Asian countries lifted well above the developing country average (Figure 1.2).

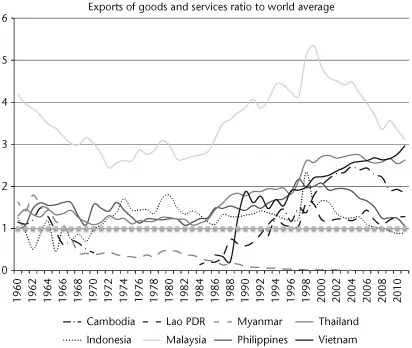

Despite this remarkably convergent growth, however, the countries of the region display a great variety of development experiences. This is due in large part to differences in initial resource endowments, systems of government and development strategies, and the pace and extent of their integration with external markets. Today’s high degree of international market integration in the region is a phenomenon with deep roots in the region’s historical role both as a unique supplier of spices and other natural resource products, and as an entrepôt on maritime trade routes linking the world’s largest economies. In recent decades, Southeast Asia’s outward orientation has been reinforced by adoption of growth and development strategies that exploit trade-based opportunities created by its abundance of labor and natural resources and by its geographic, cultural, and economic proximity to large, fast-growing economies in Northeast Asia. Countries of the region (Myanmar excepted) display high and/or rising trade intensity relative to the world average (Figure 1.3). The nature of Southeast Asia’s contemporary economic development experience is increasingly dominated by its ever-closer integration into the wider Asian and global production and trade networks for agriculture, resources, manufactures – and, increasingly, of services.

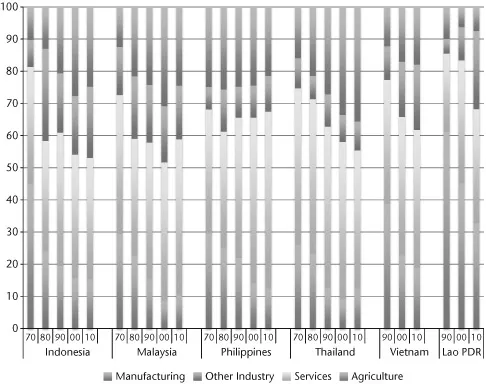

Another striking feature of the region’s recent development is the pace and extent of transformation of production and sources of household income. Fifty years ago, nearly all inhabitants of this region lived in rural areas and relied on their own labor to supply food, shelter, and other necessities of life. But in less than three decades from the early 1970s, the region’s economic center of gravity moved from primary industries (agriculture, fisheries, mining, and forestry) to manufacturing – initially, raw materials processing and simple assembly operations, but becoming more technologically sophisticated over time (Figure 1.4). This sectoral transformation occurred at a rate far higher than comparable changes in Western Europe, the United States, and Japan, and matched or exceeded rates achieved a generation earlier by the Northeast Asian “tiger” economies, Taiwan and South Korea. It has been accompanied by urbanization, rising labor productivity, and the emergence of a sizable middle class, and has to most observers been the region’s most visible manifestation of economic growth. It has resulted in Southeast Asia’s economies achieving a far more diversified pattern of production and trade than is found in other regions of the developing world. Within Southeast Asia, later starters such as Vietnam and Laos now show signs of making the transformation even more rapidly than their neighbors.

Figure 1.1 Growth of per capita income

This rate and pattern of growth has proved remarkably robust despite severe setbacks (notably the Asian Crisis of 1997–99 and the global Great Recession of 2008–10), and periods of great volatility in world markets for important regional commodity exports such as oil and gas, rice, coffee, and rubber. In resonance with the structural transformation, the sectoral basis for growth has changed over time. So too has the distribution of gains from growth among factors such as land, labor, and capital, and of course among households as owners of those factors. As a consequence, the region continues to provide a fertile ground for theorizing about economic development, just as it has since the end of the colonial era.

Figure 1.2 Per capita income as percentage of world average

Although the foregoing description suggests a group of countries that are homogeneous relative to the rest of the developing world, it goes without saying that each country’s development path has been shaped by unique features and conditions. In fact, the divergent features of country experience are as noticeable as their similarities, and understanding these after controlling for inherited factors such as natural resource wealth is an important task for scholars of Southeast Asian development. The Philippines, a promising early leader in development, experienced decades of growth at rates much lower than its neighbors, and in so doing slipped on many measures of economic wellbeing from regional leader toward the middle of the pack. In contrast Vietnam, a much later initiate to modern economic growth, has displayed remarkably rapid convergence on all key measures of wellbeing during its transition from command to semi-market economy. Meanwhile, increasingly close regional economic integration, through institutions such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as through adoption of a broadly common regional stance in relation to the Asian and world economies, surely accounts for much of the growth catch-up that can be observed in Vietnam as well as in Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar, the region’s most recent arrivals to market-based development.

Figure 1.3 Export intensity relative to world average

The goal of this chapter is to provide an overview of Southeast Asian economics and to introduce some of the key themes to be explored in later chapters. The next two sections offer a brief historical survey of regional economic development since about 1970. The emphasis is on comparisons between “then” and “now,” especially those phenomena that can be linked to outcomes such as the divergent economic growth rates of the early decades in this era, or the convergence that has occurred more recently. The chapter’s focus is more broad, however, than aggregate growth alone. Both the reality and perceptions of the distribution of the costs and the gains from growth are increasingly important political economy issues. And arguably the main point of any survey of development is to identify challenges and opportunities that the future will bring; this is the subject of the fourth section of this chapter. Finally, a concluding section provides an overview of chapters making up the remainder of the volume.

Initial conditions

In order to interpret the present, let alone to predict the future, it is necessary first to understand the past. In the generation that followed World War II, as colonialism gave way to modern states and as the geopolitical theater of the Cold War began to take shape, Southeast Asia became the subject of a wealth of studies by economists and other social scientists. Some focused tightly in on local institutions and the behaviors of farm and village communities, which they identified as organizationally distinct from urban (or “modern”) populations (Boeke 1953; Geertz 1963). Others traced the birth and early development of individual nations. Only a few chose to examine the region as an entity. By far the most famous among regional surveys is Gunnar Myrdal’s Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations (Myrdal 1968a), which meticulously documented and compared levels of living and progress in economic growth across South and Southeast Asia. The data and analyses in this landmark work of early scholarship in development economics still provide a baseline for measuring regional progress in economic development.1

Figure 1.4 Trends in sectoral structure of value added, 1970–2010

Possibly the most articulate and insightful appraisal of early economic life in the region, however, comes not from an economist but from a journalist-turned historian: the late Stanley Karnow, in his contribution to the Life World Library, a popular American series of coffee-table books. Karnow’s volume, Southeast Asia, was published in 1962. To revisit it 50 years later is to discover a fascinating mix of continuity and contrast. Karnow documents a region united by geography (he likened the map of Southeast Asia to “a huge jigsaw puzzle”) and history, and yet fractured by deep social and economic divisions. Some, such as the dichotomies between countryside and city and between wealthy and impoverished, are as familiar today as they were obvious to observers like Karnow, through the lenses of the Life photographers, or in Myrdal’s careful tables of data. For confirmation, one need only consider the sharp rural–urban divisions that define opposing factions in Thai politics since 2001, a gulf so wide that it now threatens to bring growth in this otherwise successful regional economy to a halt.

Some other divisions recorded by Karnow are much more surprising to a twenty-first-century witness. These are notably the economic and cultural chasms that seemed to divide the region’s states from one another,2 and the contrast between entrepreneurial, development-oriented states and institutions and those seemingly committed to a lethargic, inwardly-oriented status quo.3 Lastly, without the depth of perspective that history provides, it is difficult today to comprehend the theme, pervasive in Karnow’s writing and that of most of his Western contemporaries, of an unstable, hungry, and avaricious “Red” China posing an existential challenge to Southeast Asian states and threatening the wellbeing of their peoples. China remains a daily preoccupation for the region, but it is a very different China and a very different set of issues – far more economic than geopolitical – that now command regional attention.4

Economically, the early postcolonial regimes typically rendered economic policies subservient to the seemingly more pressing political tasks of state formation and nation-building. Most of these regimes harbored deep suspicions of capitalism, an economic system that they associated with colonial subjugation. To the leaders of newly independent nations, some of the most appealing alternatives were to be found in the experiences of the Soviet Union and Maoist China, whose quasi-autarkic strategies for the transition from peasant agriculture to industrialization appeared to offer an alternative to the “unequal exchange” of raw materials for manufactures imported from the West. There was also, of course, a more pragmatic motive for mistrust of trade, as Karnow realized in 1962: “As producers of raw materials, Southeast Asians have come to recognize the dangers of dependence on whimsical world markets” (p. 147). During the early postcolonial years, the intensity of Southeast Asia’s reliance on trade diminished to historically low levels (Booth 2004).

As the curtain rose on the era of modern economic development, the states of Southeast Asia were (mostly) new, their governments inexperienced, their policies ill-informed and untested, and their basic human needs very great.

The long transition

As recently as 1970 (and far later in some countries and areas) the typical Southeast Asian was rural, agrarian, undernourished, unlettered, unbanked, and unconnected to the broader world whether through markets, media, or migration. Miserable as these conditions were, however, they did not clearly distinguish this region from other developing areas. There were two phenomena, however, that set Southeast Asia apart. First, as home of the fabled Spice Islands and for centuries a key waypoint on global East–West trade routes, Southeast Asia had had a precolonial economy that was far more heavily trade-dependent than can be said for most other countries. Second, according to experts of the day the region’s development prospects, along with those of the rest of Asia other than Japan, were globally dim.

One contemporary assessment ranked “Southeast Asia” (meaning the regions we now call South, East, and Southeast Asia) below the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America on measures of per capita income, population pressure, and economic culture, concluding that “while some of the intermediate rankings are uncertain … in general the degree of poverty and general backwardness is greatest in Southeast Asia and smallest in Latin America”...