- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Explores the interdisciplinary nature and potential of the field of criminology, covering the fields of sociology, economics, psychology, biology, philosophy and religious studies. The conclusion demonstrates various theoretical approaches for policy development and discusses opportunities for incorporating academic contributions into the political process.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Introduction: A Multidisciplined Approach to Crime

Susan Guarino-Ghezzi and A. Javier Treviño

Our attempts at understanding crime are as old as our attempts at understanding the larger subject of human behavior. When Cain murdered Abel, the meaning of the act was dissected for many centuries, for many audiences, and on many levels. Today, crimes of various sorts are predictably frequent subjects in movies, books, in the news, on talk shows, and in the corner pub. Crime is a subject that nearly everyone feels qualified to debate, to have opinions about, to comment on. There are many conflicting views on crime—perhaps because the subject of crime is itself a contradiction. Literary critic Wendy Lesser (1994) has argued that we are drawn to horror films such as The Silence of the Lambs because we, the audience, identify with both of the movie’s main characters: the detective and the murderer. Even as the diabolical Hannibal Lecter assists in the investigation of the latest serial killer by putting himself into the killer’s shoes, Lecter’s audience imagines what it is like to be him. Contrast that image—of murderous impulses within the investigators—with the criminal justice system. The bureaucratic, “fact-finding” image of police investigation and courtroom trial gives the outward impression of objectivity, of “us” versus “them,” the good and bad, the law-abiders and lawbreakers.Yet, the sorting of individuals into moral and legal categories is far from a precise science.

There are those who believe that the criminal is not a distant “other,” but is lurking within ourselves. Consider the first line of Nick Lowe’s lyrics to “The Beast in Me”: “The beast in me is caged by frail and fragile bars; restless by day and by night rants and rages at the stars; God help the beast in me.” “The Beast in Me” was played on the highly rated television series “The Sopranos,” in which organized crime boss Tony Soprano ruthlessly kills to maintain dominance even as he appears to be living out the “American dream” in his upscale suburban community. Literature scholar R.A. Foakes (2003) suggests that we are fascinated by violence in the media because it provides us with a safe way to identify with it harmlessly, without acting on it, and to release impulses we normally repress. “The beast in me” may be the subconscious magnet for many talk show audiences, and it is certainly the direct subject of such literary works as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as well as many Shakespearean tragedies.

If crime is indeed about human weakness, are the causes psychological, biological, or purely moral? Mental pathology or a flawed moral-cognitive development seemed to be at the root of the ruthless murders commissioned by 1960s cult leader Charles Manson in California and the 1978 Florida murders committed by serial killer Ted Bundy. There is evidence of a psychology-crime link in the increased numbers of offenders with mental disorders as well. Biological factors including brain function, genes, male hormones, and the effects of harmful addictions have also been associated with crime. Some people view biological and psychological explanations as mere excuses; what about weak moral character and bad choices? Consider the Menendez brothers, raised in affluence, who in 1996 were convicted of mercilessly slaughtering their parents in cold blood. Although they claimed they were sexually abused, just weeks earlier the brothers were glued to “The Billionaire Boys Club,” a television mini-series based on real-life events in which a group of young men from Beverly Hills premeditated the murder of two people, including the father of one of the young men.

Psychology, biology, and morality help us to understand individual causes of crime, but they do not tell us the full story. Crime is also the result of societal/cultural weakness—society’s inability to control individuals, particularly as members of groups or subcultures. Consider the romantic attraction that many Americans have to the “wild, wild west” of defiant gun slingers such as Jesse James, or gangsters such as John Dillinger, whom many rooted for during the 1920s even as the FBI’s “G-men” worked to track him down. The ambiguous corporate culture of greed and selective lawbreaking has been blamed for such notorious white-collar crimes as junk-bond specialist Michael Milken’s multimillion-dollar violations of federal securities and racketeering laws during the 1980s, or Enron’s illegal accounting practices in 2003. Cultures need not be weak enforcers of social control, however. Amish communities in the United States and Canada provide an interesting case of a religious culture with tight-knit families and strong communities that control behavior by separating themselves from the larger society. Similarly, teenagers in Japan have been known for obedience to moral values and internationally low rates of delinquency, although Japan is now experiencing a surge in youth violence (Faiola, 2004). Recently an 11-year-old girl used a box cutter to slit the throat of a classmate and then brutally kicked her as she lay dying. Some Japanese attribute such sudden acts of rage to a long economic slump, soaring rates of divorce, domestic violence, suicide, and violent animated films, comic strips, and video games marketed to children.

As the Japanese example illustrates, crime is a societal tragedy—a failure of social institutions like families or schools to intervene and block the negative influences. Criminogenic social conditions, which lead to crime, include urban areas with high rates of unemployment, gun availability, transient communities, and violent media imagery. These conditions of the social environment shape moral choices and, if left unattended, neutralize existing social controls of family, religion, and other societal institutions.

Criminal acts also provide insight into the strong spirit of the human will to overcome social injustice. Certain individuals or groups seeking justice have been labeled “criminal” although they were struggling toward a higher purpose—showing political resistance to arrogant power-holders. Consider the fictional character of Antigone, in Sophocles’ ancient Greek drama bearing her name from around 400 BCE. After the death of Antigone’s brother, her uncle, King Creon, falsely accused the brother of treason and ordered his corpse to be placed on display rather than be given a religious burial. Ignoring the king’s threats, Antigone buried her brother and was subsequently condemned to die of starvation. Antigone committed suicide rather than wait to die, and was vindicated when the king’s son and wife also killed themselves out of grief. Similarly, under China’s strict totalitarian dictatorship, group behaviors that are not approved by the government are banned, with serious consequences for those who persist. Recent reports have described the Chinese rite of Falun Gong, a spiritual practice of group exercise that attracts thousands of adherents, many of whom are mothers and grandmothers. These reports detail how the Chinese government, threatened by any behavior that resembles a religious movement, imposes long-term detention on Falun Gong followers and labels the practice a “dangerous cult,” yet support for Falun Gong remains strong among many people.

For complex reasons, citizens as well as governments may be tempted to spread cultural myths about “bad people.” Cultural critic René Girard (1989) believes that members of every society have a deep-seated fear of danger by their enemies or natural disasters, and comfort themselves by mimicking the very violence they claim to deplore. This contradiction requires a subconscious creation of cultural myths in which innocent targets—the sinner, the witch, the counter-revolutionary, the Jew—become the scapegoat, or surrogate victim, representing all that is wrong. In anticipation of a crisis such as the great plagues of Europe or a military attack, one type of individual is arbitrarily selected as the “real” source of danger and murdered, “sacrificed” in a religious ritual, or expelled. The scapegoat is perceived as both the cause and solution to violence (Girard and Williams, 1996).

The contemporary U.S. criminal justice system, if unchallenged, would place a great deal of unchecked power into the hands of a few, and unjust laws, corrupt police, or prosecutorial malpractice would never be exposed. Once the law defines a behavior as criminal, there is a tendency to unquestioningly accept that definition and probe no further—to let “justice” take its course. Yet, as philosophers and legal activists tell us, we endanger our liberty if we merely sit back and accept the reach and command of the law. If indeed the criminal law is a way to control the dangerous impulses lurking in many of us, then those same impulses are lurking in lawmakers and enforcers as well.

Consider Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, on which the film Apocalypse Now was based. Conrad tells the story of Mr. Kurtz, an ivory trader who arrived in the heart of the jungle and established a highly successful business. His success was based on his discovery that natives treated him as a supernatural being, a mistaken belief that he exploited to control the natives and amass his wealth. Human heads, of “rebel” natives, were mounted near Kurtz’s home to reinforce his power—even though he thought of himself as a benevolent leader. Literary analyst R.A. Foakes (2003:2) observes that “Mr. Kurtz invaded the wilderness, and the wilderness [took] a terrible vengeance on him by invading him.” Mr. Kurtz was able to maintain his powerful position by following this sentiment: “Exterminate all of the brutes.” Yet Conrad was not only telling a story, but using his twisted character to illustrate the coexisting impulses in all of us. On the one hand, we have a desire to exert benevolence, to achieve the praise of those who look up to us. On the other, we have the desire to exterminate our enemies. Both impulses are prompted by the same “heart of darkness.”

If we agree to relax our definitions of “crime,” because they may be biased by existing criminal law, and talk instead about “aggression,” we see more conflicting points of view. At times aggression is not only acceptable, but encouraged and lauded—as in aggressive sales practices that may at times “fool” or “trick” consumers but are nevertheless legal. Is the law inconsistent? Do most people support aggression as long as it contributes to the functioning of a competitive society, or deals with enemies outside the borders? Perhaps contradictions built into common attitudes about aggression help to explain our fascination with news reports and fictional accounts of criminal or accidental violence.

A Short History of Criminology

Criminologists, as professionals who study crime, discuss, agree, and disagree about different issues than do neighborhood residents kicking back at the pub. While the academic criminologists will study the effect of incarceration on crime rates in society, the neighborhood group might debate how a prison cell could be made more punishing to the individual offender. Removed from the personal and concrete, most criminologists treat the study of crime from a distance, much as chemists might dispassionately write up the implications of a lab experiment.

Generally, criminologists are professionals who study three main areas of crime: (1) why laws are made, (2) why they are broken, and (3) what the societal reaction is, or should be, to the criminal offender. There are two beginnings to the history of the disciplined study of crime, or criminology. The first dates from the mid-eighteenth-century Enlightenment contributions of Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794) and English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). In their era, their ideas were revolutionary because they challenged the existing arbitrary and barbaric system of criminal law and proposed a more rational system of laws and punishments that corresponded to rational views of human behavior. Their ideas constitute what is called the “classical school” of criminology, which assumes that individuals have free will and choose their behaviors based on rational calculations of expected gains and losses.

A century later the second main influence of criminology began. This was the “positivist” revolution, most closely associated with the 1876 publication of Cesare Lombroso’s The Criminal Man. Lombroso, who was an Italian physician, proposed that the criminal was a biological “atavist”—a throwback of evolution. His claim turned out to be false, but was nonetheless influential because his research applied the scientific method of measurement and experimentation to the study of crime. Positivism, or the consideration of observable facts as opposed to philosophical ideals, eventually grew into a mainstream positivist school, as criminologists tried to emulate natural scientists by developing and testing hypotheses, measuring levels of criminality, and using their findings to support or refute theories of crime. Unlike the classical school, positivism did not assume rational free will or choice on the part of the individual, but considered how the individual was affected by “determinism,” or biological, psychological, and social factors. The notion of causality, or cause-and-effect relationships, was introduced as positivist criminologists tested the effects of multiple factors on criminal behavior by studying and comparing individuals. More than other social science disciplines, positivist criminology became known for its multidisciplinary influences from psychology, sociology, law, and biology.

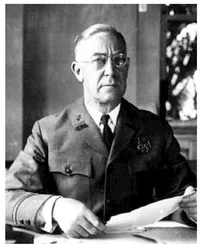

During the early part of the twentieth century, at the same time as positivist criminologists were testing and formulating theories of criminal behavior, classical criminologists continued the classical school’s tradition of analyzing the state’s response to crime. The most important U.S. figure in this area was August Vollmer, former chief of police in Berkeley, California, whose goal was that police, particularly administrators, “become broadly informed in the entire area of criminology and in the principles of such related areas as public administration, political science, psychology, and sociology” (Morris, 1975:127). Vollmer, in collaboration with law professor Alexander Marsden Kidd, developed a summer session program in criminology at the University of California in Berkeley in 1916. In 1933, the University expanded the program and formed an academic major in criminology, followed in succession by the formation of the Bureau of Criminology in the Department of Political Science (1939), a Master’s program in Criminology (1947), and in 1950 the nation’s first formal “school” of criminology, with police administrator O.W. Wilson as Dean.

August Vollmer. With permission of the Berkeley Police Department Historical Preservation Society

Vollmer also paved the way for the first professional organizations of criminologists. The National Association of College Police Officials (NACPO) was founded in 1941 by Vollmer and six other men, mostly former police officers, who taught “police science and administration” at the University of California at Berkeley. Five years later, the NACPO grew into the Society for the Advancement of Criminology, which defined criminology as “the study of the causes, treatment and prevention of crime” and included studies in crime investigation, prevention, and administration (Morris, 1975:128). The Society for the Advancement of Criminology was later renamed the American Society of Criminology (ASC). A series of newsletters and journals made their appearance during the 1950s. In the 1960s, women began to enter the field. By 1970, an early newsletter eventually grew into the current journal Criminology, which was established as the ASC’s official scholarly venue. The journal’s founding editorial policy described Criminology as “interdisciplinary,” and that claim remains with the journal today.

While the growing academic discipline of criminology drew from many fields, the meaning and implications of the term “interdisciplinary” were not always consistent. For example, “social work” was one of Criminology’s allied disciplines at the time the journal was founded, but it is no longer included in the journal’s editorial policy. Albert Morris’s (1975) history of the ASC suggests that social work’s emphasis on “how-to-do-it” courses meant that the social work discipline was too applied for the ASC’s more lofty vision of “understanding . . . what is fundamental to human experience.” Criminologist Stanley Cohen (1988), however, points out that its separation from social work practice may have cost the discipline of criminology some practical insight.

Morris (1975:162) offers four different approaches on what it means to be interdisciplinary in the study of crime:

- Individualistic application: Scholars trained in different disciplines apply their specialized knowledge to particular aspects and special areas of criminology. For example, sociologist Edwin H. Sutherland, who specialized in how individuals acquire knowledge through social interaction, studied professional fences who first apprenticed and then mastered the skills needed to buy and sell stolen property. Economist Anne Piehl has used economic theories of rational choice and cost-benefit analysis to evaluate the deterrent value of Operation Ceasefire, a program that seeks to control gang...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Contents

- Chapter One Introduction: A Multidisciplined Approach to Crime

- Chapter Two Sociological Perspectives on Crime

- Commentary

- Chapter Three Economics and Crime

- Commentary

- Chapter Four Psychological Perspectives on Crime

- Commentary

- Chapter Five Biological Perspectives on Crime

- Commentary

- Chapter Six Philosophy and Crime

- Commentary

- Chapter Seven Religious Studies and Crime

- Commentary

- Chapter Eight Conclusion: Toward an Interdisciplinary Understanding of Crime

- About the Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Crime by Susan Guarino-Ghezzi,A. Javier Trevino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Criminal Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.