![]()

Part I

Theory and Research

![]()

One

The Psychosocial and Physical Challenges of Cancer

The literature on the psychological, interpersonal, and physical challenges posed by cancer is voluminous and has grown exponentially since the early 1970s, when Jimmie Holland, MD, pioneered the field of psycho-oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (Holland, 2002). At the same time, Moorey and Greer (2012) began the development of Cognitive Behavior Therapy for cancer, on the basis of early literature regarding the psychosocial impact of cancer. For our purposes, it may be useful to categorize the literature, and our treatment formulations, on the basis of the following:

- The most commonly occurring psychological and adaptive difficulties associated with cancer,

- The phase of treatment and survivorship of the cancer patient,

- Adapting for site and stage of cancer as well as effects of both the cancer and treatment,

- Use of a CBT case conceptualization to tailor the formulation to the specific idiographic needs of each patient.

Moorey and Greer (2012) outlined the psychological and interpersonal challenges that a diagnosis of cancer creates. These responses may include an initial sense of shock and disbelief, as one begins to process the meaning of cancer as a potential existential threat. Cancer, in the CBT model employed by Moorey and Greer, threatens the core beliefs, rules, and assumptions that have explicitly and implicitly guided the person in his or her daily life. A diagnosis of cancer can threaten the entire system of meaning by which one’s life is organized. Drawing on the work of Lazarus and Folkmann (1984), they described responses to stress as affected by the person’s appraisals of the situation. Moorey and Greer (2012) focused on how the person’s appraisals of the threat posed by cancer can be organized into what they describe as five adjustment styles:

- Fighting spirit

- Avoidance or denial

- Fatalism

- Helplessness and hopelessness

- Anxious preoccupation.

The person who sees illness as a challenge to be managed exemplifies a fighting spirit. Such people seek information, are actively engaged in their treatment and recovery processes, and refrain from dwelling via rumination and unproductive worry. As one patient described, “We are a family that believes in playing the cards we’re dealt. And we play them as well as possible.”

Avoidance or denial may be a way of keeping intense fear states at bay, but it comes at a price. By not facing the emotional impact of the disease, the person may cut himself or herself off from valuable sources of information from within. In addition, avoidance and denial can prevent the patient from not only facing “the cards they are dealt” but also engaging in effective problem-solving behaviors and from being meaningful collaborators in their own care. Fatalism is essentially a passive stance toward illness and illness management. It may superficially resemble acceptance, but true acceptance is a form of engagement, from which spring forth adaptive responses to life’s challenges. Fatalism, on the other hand, tends not to lead to active adaptive responses, where such responses are indicated and warranted. In helplessness and hopelessness, the patient is overwhelmed and simply gives up. This is a classically depressive response. Anxious preoccupation is characterized by prolonged worry states and maladaptive reassurance seeking. We will see in Chapter 7 on treatment of cancer-related anxiety that an understanding of both cognitive biases and maladaptive cognitive processes and coping strategies inform treatment efforts.

In addition to Moorey and Greer’s Beckian CBT model, Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) is an empirically supported treatment. PST adds to the understanding of how people with cancer cope with a diagnosis and treatment of cancer, by referring to the person’s problem orientation (Nezu et al., 1999; Nezu et al., 2007). The Nezus have categorized the person’s problem orientation in terms of the following:

- Positive problem orientation, in which problems are seen as a normal, expectable part of life. Problems are viewed as challenges to be solved or mastered, and the person views himself or herself as capable of dealing with life’s problems. The person recognizes that persistence and effort are required to solve problems, and that engagement, rather than avoidance, is required.

- Negative problem orientation occurs when problems are viewed as large, unsolvable threats, with the person lacking the resources to manage the threat effectively. The person may become prone to emotion dysregulation in the face of problems, leading to the use of ineffective problem-solving styles, as follows.

In addition, they have described three problem-solving styles, one of which is effective:

- Rational problem-solving style, which is a systematic and deliberate strategy of engagement;

- Impulsivity/carelessness style, which involves seeing few solutions to a problem and impulsively selecting one without thinking through the consequences;

- Avoidance style, characterized by passivity, denial, avoidance, and reliance on others to solve the problem.

While there are data supporting the efficacy of these two approaches, the relationship between problem orientations/adjustment styles and cancer outcome is equivocal. Hopelessness and helplessness are associated with poorer disease outcome, while the more active, engaged styles and orientations do not necessarily ensure improved cancer outcome (Garssen, 2004). Promoting a more engaged style of coping may nonetheless improve quality of life and reduce the burden of psychological distress.

The data regarding depression and anxiety disorders in newly diagnosed and treated cancer patients have revealed considerable variability in prevalence estimates. Levin and Kissane (2006) reported that major depression may occur in 10% to 25% of cancer patients. Li et al. (2012) reported major depression in approximately 16% of cancer patients. However, distress from depression symptoms can be significant, even if the patient does not meet the more restrictive criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD). And if we use depressive symptoms rather than MDD as our criteria, up to 58% of cancer patients may report depressive symptoms (Massie, 2004). Li et al. (2012) reported minor depression and dysthymia in 22% of cancer patients. Since fatigue and appetite problems can result from cancer and cancer treatment and not just from depression, it is worth teasing out these processes. When doing so, and substituting cognitive symptoms for fatigue and appetite difficulties, depressive rates are unchanged (Trask, 2004; Levin & Kissane, 2006). It is likely that when employing Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria, the prevalence of depression in cancer patients may be twice that of the general U.S. population (Jacobsen & Andrykowski, 2015). And, suicide is twice as likely to occur in cancer patients than in those without cancer (Misono et al., 2008). It is clinically important to recognize that cancer-related depression “is associated with fewer core depressive thoughts, such as a sense of guilt and failure, dissatisfaction and self-dislike, than primary depression” (Li et al., 2012, p. 1188). In addition, the prevalence of depression in cancer patients is equally distributed between men and women, unlike the roughly 2:1 male:female prevalence of depression in the general population, possibly due to the more even split of the disease’s occurrence (Li et al., 2012).

Similar variability exists in prevalence of anxiety problems in cancer patients, with rates ranging from 0.9% to 49% (van’t Spijer et al., 1997). Levin and Kissane (2006) described estimates ranging from 15% to 28%, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales. Mitchell et al. (2011) placed the prevalence of anxiety disorders in cancer patients at 10.3%. A study of adult outpatients in a large cancer center has shown that 34% of patients reported significant problems with anxiety (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al., 2009). Sub-syndromal anxiety can be quite distressing and may be related to situational and/or existential concerns, such as panic occurring in cancer patients who have young, dependent children (Traeger et al., 2012). Anxiety problems can be transient or episodic, such as anxiety associated with upcoming procedures or outpatient return visits for monitoring by the oncology team. Vulnerability to anxiety disorders is increased by having a history of anxiety disorders prior to the onset of cancer, though medical phobias, features of post-traumatic stress disorder, panic, and worry are quite possible in the absence of a prior history of anxiety disorders.

Clinically significant anxiety and depressive problems are the psychological problems most likely to occur in newly diagnosed and treated patients as well as those with newly diagnosed recurrences (Jacobsen & Andrykowski, 2015). Factors affecting the presence of depression include hopelessness, lack of social support, a prior history of depression, and adverse childhood experiences. It is also possible that the biology of cancer, in some cases, such as pancreatic cancer, may also confer risk for depression. Similarly, some chemotherapy treatments, too, may induce depression (Jacobsen & Andrykowski, 2015). Steroids can be implicated in depression in cancer patients, as can some immunotherapies (Musselman et al., 2001). Stage of cancer is less predictive of depression, anxiety, or distress than one might expect (Levin & Kissane, 2006).

Difficulties with estimating prevalence rates of depressive and anxiety disorders reflect measurement issues as well as differentiating between distress occurring in syndromal versus sub-syndromal depression and anxiety. A more common approach to screening has involved assessing global distress, rather than beginning by seeking a DSM diagnosis. When using simple visual analog scales or thermometers, patients can be simply and quickly screened in a way that correlates well with more formal psychiatric assessments, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and identifies up to 19% of patients as a concern (Jacobsen et al., 2005; Levin & Kissane, 2006). Distress alone, however, is an imperfect indicator of a need for referral to a behavioral health clinician. Many distressed patients experience a reduction in their distress over the course of cancer treatment, suggesting that distress at the time of an initial diagnosis is not necessarily a predictor of a need for psychological services (Salmon et al., 2015). In addition, patients newly diagnosed with cancer are customarily distressed, yet may be highly resistant to focusing on their emotional reactions (Baker et al., 2013).

In addition to the psychological effects of being diagnosed and treated for cancer, there are physical effects of cancer and cancer treatment, which intertwine with and influence adaptive behavior and coping. The most common physical effects are fatigue and pain. Between 60% and 90% of patients in treatment for cancer may report clinically significant fatigue (Flechtner & Bottomley, 2003), with fatigue continuing to be a potential problem for years after the completion of treatment. CBT has demonstrated efficacy in managing the effects of fatigue and pain in cancer patients (Jacobsen & Andrykowski, 2015). Significant pain, for example, affects perhaps 25% to 33% of patients (Jacobsen & Andrykowski, 2015). The causes and maintaining factors in cancer pain are complex and include the disease site and severity; the use of surgical, radiation, or chemotherapies, and psychological factors that contribute to pain. The latter include a tendency toward a catastrophizing cognitive response, hopelessness, isolation, and withdrawal, in addition to anxious arousal and worry. The response of caregivers to pain may also serve as a maintaining factor for pain.

The number of patients surviving 5 years or more after a cancer diagnosis has grown steadily over the past 35 years and will continue to do so. Estimates have suggested “a 37% rise in the U.S. population living for 5 or more years with a cancer diagnosis is expected over the next decade” (Stanton et al., 2015, p. 160). Thus, by 2022, 67% of the estimated 18 million people diagnosed with cancer will survive beyond 5 years (deMoor et al., 2013). The service needs for this large number of people will be extraordinary. In addition, we will need to evolve our service models in order to address the challenges that cancer patients and their families will face throughout the long and changing course of survivorship. Part of that challenge will involve helping people adjust to the possible long-term consequences of cancer and cancer treatment: fatigue, pain, body image changes, changes in sexual functioning, family impact, work and income effects, and changes in one’s sense of meaning and purpose in life.

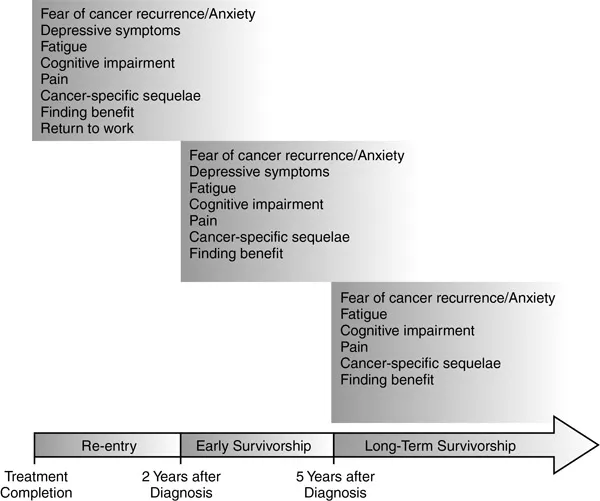

Patients who are in the survivorship phase, which begins at treatment completion, have their own commonly occurring challenges, which may vary over the course of survivorship. (Stanton et al., 2015) conceptualized survivorship as containing three broad phases or stages:

- The re-entry phase, extending from the end of treatment to roughly two years after diagnosis;

- Early survivorship, from 2 to 5 years post diagnosis;

- Long-term survivorship, from 5 years post diagnosis and beyond.

The authors were careful to indicate that theirs is a rough heuristic and that the course of survivorship is not yet fully understood. But the heuristic (see Figure 1.1) is nonetheless useful in conceptualizing problems and in organizing our treatment efforts with patients who are post treatment.

Figure 1.1 Hypothesized Periods of Cancer Survivorship and Associated Sequelae: An Evolving Heuristic Model

Figure 1.1 organizes phases of survivorship and points the clinician to commonly occurring challenges and protective factors in these phases. This, in turn, helps us organize our assessment and clinical inquiry and target relevant problems. The re-entry phase can be viewed as a time when treatment ends, and the patient no longer requires such frequent contact with the cancer treatment team. Re-entry into daily life can include a return to work, with whatever limitations are imposed by the illness and by the effects of treatment. The patient faces the need to adjust expectations and performance accordingly. In addition, the patient’s support network may have mobilized for the treatment phase and may be less prepared for the sometimes slow pace of recovery. This may be especially true when cancer pain and fatigue linger. Depressive irritability, withdrawal, and anxiety all can affect not only the patient but also his or her social network, setting up vicious cycles of interactions that may deepen depression and anxiety. Finally, the end of treatment can be accompanied by an increase of fear and worry, as the patient loses frequent contact with the medical team. During re-entry, the patient can become more focused on physical sensations and symptoms, which can in turn be interpreted in a catastrophic light, leading to health anxiety when the medical team is not available for frequent reassurance and support (Stanton et al., 2015). In essence, the medical team can become a safety behavior (Salkovskis, 1996a), and the patient’s dependence on the team for reassurance can be counterproductive. Psychoeducation, with opportunities to adjust expectations for recovery, can be a vital intervention when patients and families may otherwise...