This is a test

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

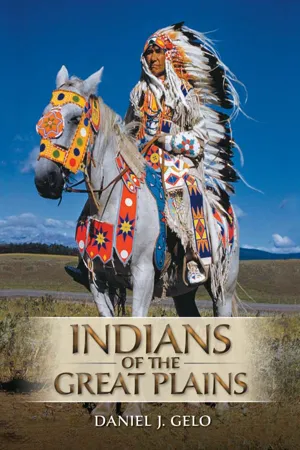

Indians of the Great Plains

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Plains Societies and Cultures

Indians of the Great Plains, written by Daniel J. Gelo of The University of Texas at San Antonio, is a text that emphasizes that Plains societies and cultures are continuing, living entities.

Through a topical exploration, it provides a contemporary view of recent scholarship on the classic Horse Culture Period while also bringing readers up-to-date with historical and cultural developments of the 20th and 21st centuries. In addition, it contains wide and balanced coverage of the many different tribal groups, including Canadian and southern populations.

Teaching & Learning Experience:

- Improve Critical Thinking - Indians of the Great Plains provides recent scholarship and up-to-date historical and cultural developments of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries to see the Plains societies and cultures as continuing, living entities — including charts showing tribal organization and kinship systems.

- Engage Students — Indians of the Great Plains features excerpts of Native poetry, songs, and ethnographic accounts, as well as Chapter Summaries and End-of-Chapter Review Questions.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Indians of the Great Plains by Daniel J. Gelo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE GREAT PLAINS

The land is great.

When man travels on it he will never reach land’s end;

But because there is a prize offered

To test a man to go as far as he dares,

He goes because he wants to discover his limits.

That wind, that wind

Shakes my tipi, shakes my tipi

And sings a song to me.

And sings a song to me.

—Kiowa Gomda Dawgyah (“Wind Songs”) as sung by Sallie Hokeah Bointy (Boyd 1981:18, 19)

THE PLAINS LANDSCAPE

Knowledge of the environment must be the basis for any discussion of Plains Indian culture. In Plains landforms, weather, animals, and plants, we see the origins of Indian adaptive regimes and material culture, migration patterns and tools, and hunting practice and house styles; and it is not too much to say that language, cognition, and religious symbolism—elements often included under the term “worldview”—are also influenced by natural surroundings.

The early Plains anthropologist Clark Wissler (1870–1947) noted that culture “approaches geographical boundaries with its hat in its hand.” Recognizing the influence of geography or environment on culture requires caution, however. It would be a mistake to accept the notion that surroundings strictly determine the cultural development and customs of a people, when humans show great adaptability and their prior customs can exist under new circumstances. Another pitfall is the concept that certain people have a unique relationship to nature that is the product of some exclusive mystical or spiritual disposition. It is possible to appreciate Indian knowledge and respect for nature without regarding their sensitivities as superhuman. Like any environment, the Plains region presents a distinct set of opportunities and limits to the humans who encounter it. Exploring the physical characteristics of the region is a good way to start understanding its inhabitants.

Where and what are the Plains? There have been several attempts to determine the boundaries of the region in geographic and ecological terms. A good starting point is the outline offered by the historian Walter Prescott Webb in his classic work The Great Plains (1981; orig. 1931). Webb tells us that a plains environment has three characteristics: it is a comparatively level surface of great extent, it is unforested, and its rainfall is not sufficient for ordinary intensive agriculture. In North America, a level surface extends for the most part between the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains. The unforested area of the continent, though, is mostly west of the Mississippi. It begins at the timber line, an artificial boundary where deep woods yield to brush and grass, running on the east generally between the 94th and 98th meridians (east Texas and Oklahoma, western Missouri and Minnesota) but veering east to the 87th meridian around 40°N, or the area around Iowa and Illinois. Discounting the timber of the Rocky Mountains, this unforested zone extends west to the Sierras and Coast ranges of California, Oregon, and Washington. The dry zone of the continent extends from the 20-inch rainfall line, the so-called “humid line” running roughly along the 98th meridian, again west to the Pacific ranges excepting the Rockies.

The area where all three key characteristics come together—the dry, untimbered, level land between the 98th meridian and the Rockies—is known as the Great Plains. The wetter untimbered level land east of the 98th meridian is also of interest as a zone showing related Indian cultural adaptations; this area is referred to as the Central Plains, Central Lowland, or simply the Prairie. Both the Great Plains and the Prairie are considered in this book (see Map 1.1). Elevation as well as moisture distinguishes the Great Plains from the Prairie, with the Lowland rising no more than 1,500–2,000 feet above sea level and the Great Plains rising from this elevation to around 5,500 feet at the foot of the Rockies. Thus, another name for Great Plains is “High Plains.” Transition between Lowlands and High Plains is gradual, but abrupt between the Plains and Rocky Mountains. The entire Great Plains grassland region is bounded on the north by the boreal forests and lakes of subarctic Canada, and the conventional boundary on the south is the Rio Grande.

The most noticeable difference between the Great Plains and Prairie is in the kinds of grasses that are dominant in the groundcover under natural conditions. Short-grass species are characteristic in the Plains. Short grasses often form a mat of intertwined roots, though this sod gives way to separate tufts or “bunch grass” toward the drier west. Blue grama and various other types of grama and buffalo grasses are common, along with little bluestem, western wheatgrass, galleta, needle-and-thread grass, mesquite grass, and three-awn grass. The Prairie, by contrast, contains taller grasses, some growing to 6 feet or more by autumn: big bluestem, little bluestem, Indian grass, switch grass, and needle grass. Dense sod develops in the moister east, and a square yard of Prairie turf contains literally miles of tangled roots. The transition between tall and short grasses is actually gradual, and many ecologists see at the heart of the mid-continental grasslands a mixed-grass zone featuring the medium-sized little bluestem plus shorter species. The main grass types in any area coexist with one another and several others in a number of patterns depending on local conditions. Tall-grass outliers have been found far to the west, while rivers, pond areas, and sand hills harbor atypical communities. Each grass community has its own character as well because of the particular forbs (broad-leaved weeds and wildflowers) that it hosts.

One of the reasons tall grass thrives toward the east is that the soil is deeper and richer there. Mid-continental soils lay on a foundation of marine rock sheets which are uplifted to varying degrees and which generally slant toward the east. One can see in road cuts in central Texas, for example, thick limestone beds chock full of oceanic fossils, mere inches below the topsoil. At a macro level, the soils have been deposited on the rock sheets through the millennia as streams from the eroding Rockies carry mineral and organic debris eastward and, losing energy along the way, drop their sediments in alluvial fans. These huge deltas have spread, overlapped, and clogged their streams and been re-cut in a continuous process. In addition, till left by Ice Age glaciers is found in parts of Montana and the Dakotas, and silts from the Appalachians have been washed westward onto the eastern Prairie. Wind and local runoff further distribute the soils, and they are enhanced with decaying plant matter. These workings have combined to produce a relatively barren Great Plains and a Prairie region with some of the richest dirt on the planet.

Map 1.1 The Great Plains.

FIGURE 1.1 Short grass and playa on the vast, level Staked Plains near Amarillo, Texas.

The western soils based on soluble limestone drain quickly and dry out, though water may be held deep below. Sedimentary sandstone, siltstone, shale, and gypsum all occur in formations on a local and regional scale. There are also remnants of ancient volcanic activity—granite, quartzite, rhyolite—on the High Plains. Huge deposits of soft coal of various grades underlie sections of the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico. Oil and natural gas are widespread, with important producing areas around Williston, North Dakota, Denver, and the Permian Basin of West Texas. Metals are absent, with one important exception: gold is mined in southwestern South Dakota, and its discovery there in the 1870s sparked U.S. government efforts to seize the area from Native peoples. The Homestake Mine near Deadwood is the site of the greatest known U.S. gold reserves.

Toward the west, in the shadows of the Rockies, where erosive forces are greatest, and in other transitional areas the land surface is heavily scarred, with solitary hills and plateaus, large canyons, and narrower ravines that are known regionally as “arroyos,” “gulches,” or “draws.” An old saying of the Comancheros, the Hispanic traders in the Texas Panhandle, had it that “There are mountains below the Plains,” describing the effect of coming to the edge of a large canyon like Palo Duro and seeing within it a range of hills whose crests were below the horizon. Areas of monumental erosion such as those occurring where one geologic zone gives way to another are often termed “badlands” or “breaks.”

FIGURE 1.2 Tall-grass prairie in Minnesota.

FIGURE 1.3 Badlands in South Dakota.

Weather works on the landforms and soil, and works with these features to determine the course of life. The meteorological forces shaping the Plains are among the most remarkable anywhere. Webb noted long ago that the wind blows harder and more constantly on the Plains than any place in the United States except for some Pacific Coast areas. Winds prevail from the west with average hourly speeds of as much as 10–14 miles per hour (mph), comparable to the Outer Banks of the North Carolina shore and twice the rate found in the intermontane west. The winds are of high velocity, with special erosive power resulting from the abrasive sediments they carry.

The wind is everywhere, and the humming telephone wires and waving grass can be more ominous than comforting for those who know the power of its aberrant forms. The chinook is a warm, dry wind plunging from the east slopes of the Rockies at 70–100 mph that can raise the temperature by 40°F within a day. The chinook may moderate harsh winter conditions, exposing grass for hungry grazing animals, but the rapid thawing of snow and flash flooding can be dangerous as well as helpful. Polar air masses descending in winter toward the southern Plains, called “northers,” cause temperatures to plummet rapidly. Blizzards, intense snowstorms characterized by snowdrifts and sub-zero temperatures, are another winter weather hazard. During drought the wind blows yellow and then black with dust, producing “rollers” or enormous clouds that inundate and sandblast the landscape. Dust storms are most prevalent after spotty rainfall has promoted the buildup of loose sediments. Dust carried by a Great Plains storm can be deposited 1,800 miles away.

The most dramatic windstorms are the tornados. These whirlwinds occur mainly in the spring and summer, in the imaginary 500-mile-wide corridor called “tornado alley,” running from Texas to the Dakotas or Illinois, depending on the yearly pattern. Southwestern Oklahoma sees the greatest frequency. Winds rotating to form the tornado funnel reach speeds of 100–300 mph. The funnel can be very capricious in the way it does damage, removing the roof from a house without upsetting the breakfast dishes, imploding the house next door, and missing the next house altogether. Most tornados run briefly across open lands, but about 20 every year do significant damage to communities. In their artwork and stories, the Kiowas still vividly recall the twister that flattened much of Snyder, Oklahoma, on May 10, 1905, claiming at least 97 lives. Three tornadoes that dropped from the sky near Wichita Falls, Texas, on April 10, 1979 cut paths as much as a mile wide and 60 miles long, killing 56 people, injuring 1,916, and causing losses for 7,759 families. Prior to dense Euro-American settlement, tornados would not have exacted such a heavy toll, but they must still have appeared awesome to Plains inhabitants. Even their smaller cousins, the dust devils that arise in the midday sun, are often regarded as dangerous spirits in traditional Indian belief.

FIGURE 1.4 A huge wall of dust races in front of a supercell thunderstorm in Parmer Country, Texas.

Winter on the Plains in general is bitterly cold, producing some of the continent’s lowest temperatures, as low as −60°F. An old saying on the Plains is that there is nothing between Texas and the North Pole but some barbed wire. There is no relief to block the descent of polar air masses or large bodies of water to moderate continental cooling. The daily average temperature in January is between 0°F in the Canadian provinces to 50°F in Texas. Summers are also extreme, with daily average temperatures in July ranging from 60°F in Canada to 85°F in Texas and record highs of 120°F. The normal absence of cloud cover allows rad...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Original Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Great Plains

- 2 Plains Prehistory

- 3 Bison, Horse, and Hoe

- 4 Tribal Organization

- 5 Family and Social Life

- 6 Material Culture and Decorative Arts

- 7 Music and Dance

- 8 Oral Traditions

- 9 Religious Fundamentals

- 10 Group Rituals

- 11 External Relations

- 12 Life Through the Twentieth Century

- 13 Contemporary Plains Indian Life

- Bibliography

- Credits

- Index