- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This unique work bridges the gap between theory and practice in organizational behavior. It provides a practical guide to real-life applications of the 35 most significant theories in the field.

The author describes each theory, and then analyzes its usefulness and importance to the successful practice of management. His analysis covers key managerial topics such as goal setting, training and development, assessment, job enrichment, influence processes, decision-making, group processes, organizational development, organizational structuring, and effective organizational operation.

Information

PART I

THE CORNERSTONES OF SCIENTIFIC THEORY AND PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

CHAPTER 1

ON THE NATURE OF THEORY

How Theory Is Embedded in Science

Theory Defined

How Theory Works

Assumptions of Science, Theorizing, and Testing Theory

Theory Building

Defining a Good (or Strong) Theory

Criteria

Implications of Good and Bad Theory

Scientific Decision Making

Conclusions

We are concerned with the relationship between theory, embedded as it is in science, and practical applications. As a starting point we focus on the nature of theory.

HOW THEORY IS EMBEDDED IN SCIENCE

Science is an enterprise by which a particular kind of ordered knowledge is obtained about natural phenomena by means of controlled observations and theoretical interpretations; thus theory is at the heart of science from the beginning. Ideally this science, of which organizational behavior is a part, lives up to the following:

1. The definitions are precise.

2. The data-collecting is objective.

3. The findings are replicable.

4. The approach is systematic and cumulative.

5. The purposes are understanding and prediction and, in the applied arena, control (Berelson and Steiner 1964).

The usually accepted goals of scientific effort are to increase understanding and to facilitate prediction (Dubin 1978). At its best, science will achieve both of these goals. However, there are many instances in which prediction has been accomplished with considerable precision, even though true understanding of the underlying phenomena is minimal; this is characteristic of much of the forecasting that companies do as a basis for planning, for example. Similarly, understanding can be far advanced, even though prediction lags behind. For instance, we know a great deal about the various factors that influence the level of people’s work performance, but we do not know enough about the interaction of these factors in specific instances to predict with high accuracy exactly how well a certain individual will do in a particular position.

In an applied field, such as organizational behavior, the objectives of understanding and prediction are joined by a third objective—influencing or managing the future, and thus achieving control. An economic science that explained business cycles fully and predicted fluctuations precisely would represent a long step toward holding unemployment at a desired level. Similarly, knowledge of the dynamics of organizations and the capacity to predict the occurrence of particular structures and processes would seem to offer the possibility of engineering a situation to maximize organizational effectiveness. To the extent that limited unemployment or increased organizational effectiveness are desired, science then becomes a means to these goals. In fact much scientific work is undertaken to influence the world around us. To the extent that applied science meets such objectives, it achieves a major goal; this is where matters of practical application come in.

Scientific method evolves in ascending levels of abstractions (Brown and Ghiselli 1955). At the most basic level, it portrays and retains experience in symbols. The symbols may be mathematical, but to date in organizational behavior they have been primarily linguistic.

Once converted to symbols, experience may be mentally manipulated, and relationships may be established.

Description utilizes symbols to classify, order, and correlate events. It remains at a low level of abstraction and is closely tied to observation and sensory experience. In essence it is a matter of ordering symbols to make them adequately portray events. The objective is to answer “what” questions.

Explanation moves to a higher level of abstraction in that it attempts to establish meanings behind events. It attempts to identify causal, or at least concomitant, relationships so that observed phenomena make some logical sense.

Theory Defined

At its maximal point, explanation creates theory. Scientific theory is a patterning of logical constructs, or interrelated symbolic concepts, into which the known facts regarding a phenomenon, or theoretical domain, may be fitted. A theory is a generalization, applicable within stated boundaries, that specifies the relationships between factors. Thus it is an attempt to make sense out of observations that in and of themselves do not contain any inherent and obvious logic (Dubin 1976). The objective is to answer “how,” “when,” and “why” questions.

Since theory is so central to science, a certain amount of repetition related to this topic may be forgiven. Campbell (1990) defines theory as a collection of assertions, both verbal and symbolic, that identifies what variables are important for what reasons, specifies how they are interrelated and why, and identifies the conditions under which they should be related or not. Sutton and Staw (1995) place their emphasis somewhat differently, but with much the same result. For them theory is about the connections among phenomena, a story about why acts, events, structure, and thoughts occur. It emphasizes the nature of causal relationships, identifying what comes first as well as the timing of events. It is laced with a set of logically interconnected arguments. It can have implications that we have not previously seen and that run counter to our common sense.

How Theory Works

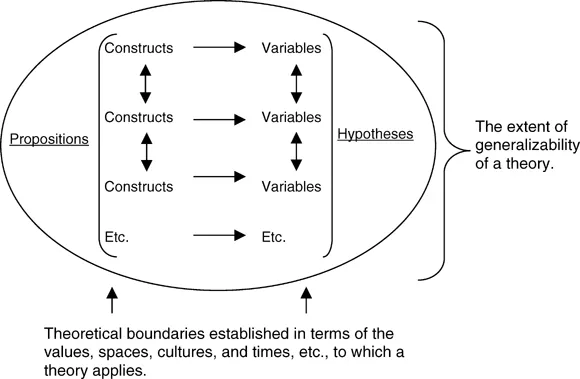

Figure 1.1 provides a picture of the components of a theory. A theory is thus a system of constructs and variables with the constructs related to one another by propositions and the variables by hypotheses. The whole is bounded by the assumptions, both implicit and explicit, that the theorist holds with regard to the theory (Bacharach 1989).

Figure 1.1 The Components of Theories and How They Function

Constructs are “terms which, though not observational either directly or indirectly, may be applied or even defined on the basis of the observables” (Kaplan 1964, 55). They are abstractions created to facilitate understanding. Variables are observable, they have multiple values, and they derive from constructs. In essence they are operationalizations of constructs created to permit the testing of hypotheses. In contrast to the abstract constructs, variables are concrete. Propositions are statements of relationships among constructs. Hypotheses are similar statements involving variables. Research attempts to refute or confirm hypotheses, not propositions per se.

All theories occupy a domain within which they should prove effective and outside of which they should not. These domain-defining, bounding assumptions (see Figure 1.1) are in part a product of the implicit values held by the theorist relative to the theoretical content. These values typically go unstated and if that is the case, they cannot be measured. Spatial boundaries restrict the effective use of the theory to specific units, such as types of organizations or kinds of people. Among these, cultural boundaries are particularly important for theory (Cheng, Sculli, and Chan 2001). Temporal boundaries restrict the effective use of the theory to specific time periods. To the extent they are explicitly stated, spatial and temporal boundaries can be measured and thus made operational. Taken together, they place some limitation on the generalizability of a theory. These boundary-defining factors need not operate only to specify the domain of a theory, however; all may serve in stating propositions and hypotheses as well. For example time has recently received considerable attention as a variable that may enter into hypotheses (George and Jones 2000; Mitchell and James 2001).

Organizational behavior has often been criticized for utilizing highly ambiguous theoretical constructs—it is not at all clear what they mean (see, for example, Sandelands and Drazin 1989). This same ambiguity can extend to boundary definitions and domain statements. In a cynical vein Astley and Zammuto (1992) even argue that this ambiguity is functional for a theorist in that it increases the conceptual appeal of a theory. Conflicting positions do not become readily apparent, and the domain of application may appear much greater than the empirical reality. The creation of such purposeful ambiguity can extend the constructs and ideas of a theory into the world of practice to an extent that is not empirically warranted. Not surprisingly these views immediately met substantial opposition (see, for example, Beyer 1992). The important point, however, is that science does not condone this type of theoretical ambiguity. Precise definitions are needed to make science effective (Locke 2003), and a theory that resorts to ambiguity is to that extent a poor theory.

ASSUMPTIONS OF SCIENCE, THEORIZING, AND

TESTING THEORY

Science must make certain assumptions about the world around us. These assumptions might not be factually true, and to the extent they are not, science will have less value. However, to the extent science operates on these assumptions and produces a degree of valid understanding, prediction, and influence, it appears more worthwhile to utilize them. Science assumes, first, that certain natural groupings of phenomena exist, so that classification can occur and generalization within a category is meaningful. For some years, for instance, the field then called business policy, operating from its origins in the case method, assumed that each company is essentially unique. This assumption effectively blocked the development of scientific theory and research in the field. Increasingly, however, the assumption of uniqueness has been disappearing, and generalizations applicable to classes of organizations have emerged (see, for instance, Steiner and Miner 1986). As a result, scientific theory and research are burgeoning in the field of strategic management.

Second, science assumes some degree of constancy, or stability, or permanence in the world. Science cannot operate in a context of complete random variation; the goal of valid prediction is totally unattainable under such circumstances. Thus objects and events must retain some degree of similarity from one time to another. In a sense this is an extension of the first assumption, but now over time rather than across units (see McKelvey 1997 for a discussion of these premises). For instance, if organizational structures, once introduced, did not retain some stability, any scientific prediction of their impact on organizational performance would be impossible. Fortunately they do have some constancy, but not always as much as might be desired.

Third, science assumes that events are determined and that causes exist. This is the essence of explanation and theorizing. It may not be possible to prove a specific causation with absolute certainty, but evidence can be adduced to s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I. The Cornerstones of Scientific Theory and Practical Applications

- Part II. From Motivation Theory to Motivational Practice

- Part III. From Leadership Theory to Leadership Practice

- Part IV. From Decision-Making Theory to Decision-Making Practice

- Part V. From Systems Theory to The Processes and Structures of Organizations

- Part VI. From Bureaucracy-Related Concepts to the Processes and Structures of Organizations

- Part VII. From Sociological Concepts of Organization to Macro-Organizational Functioning

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Organizational Behavior 4 by John B. Miner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.